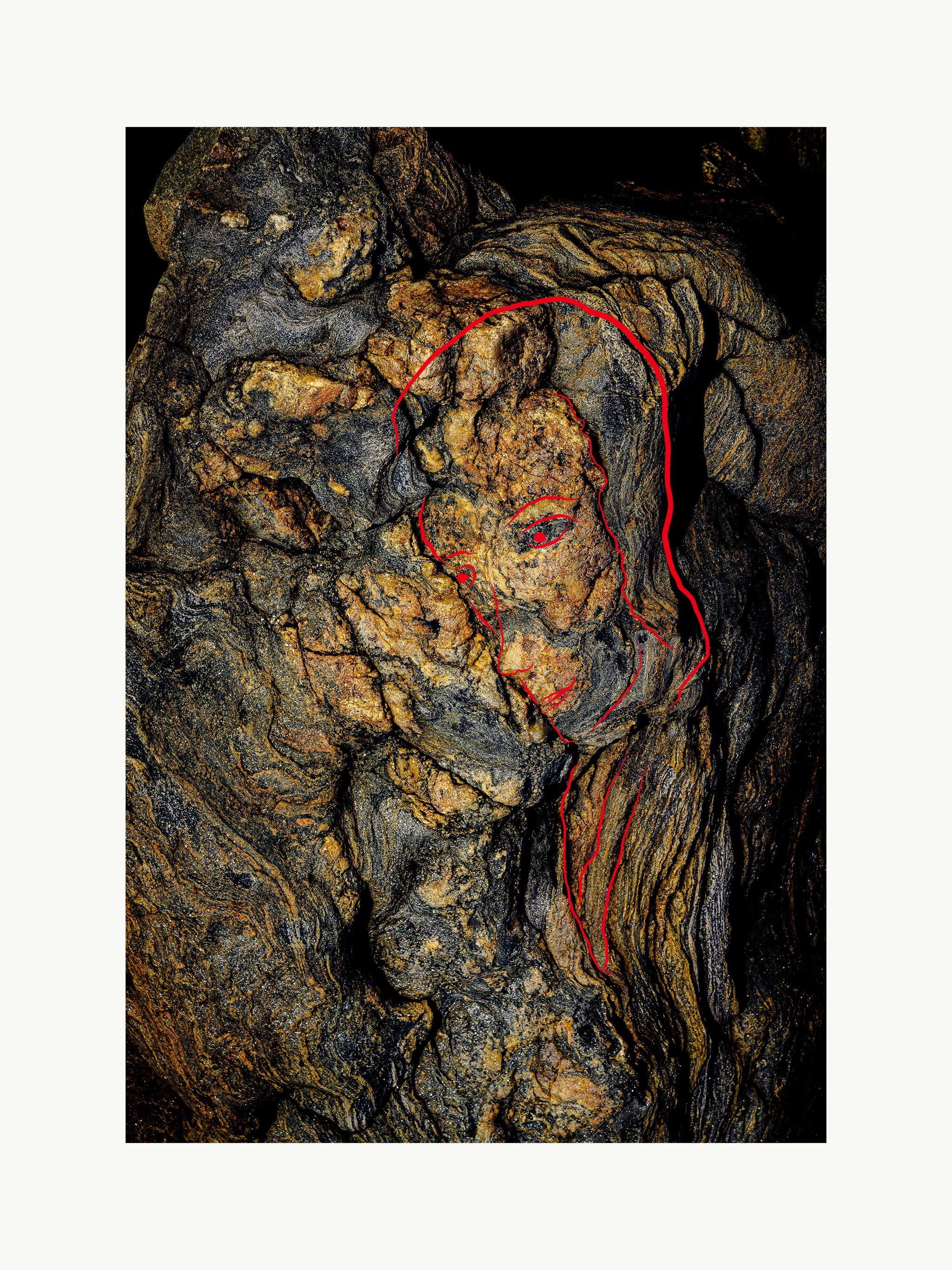

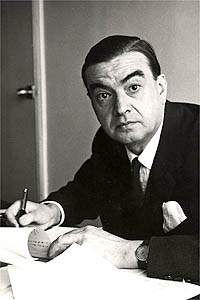

I never know where my reading will take me next. Today I was investigating the intersection of Pareidolia, Apophenia, and Mimesis (looking for a better handle on creatures seen in rocks and wood and ice) and stumbled upon the work of Roger Caillois (1913-1978), a sometime Surrealist, sociologist, philosopher and collector of rocks. The term “lithic scrying” appears in several descriptions of his activities.

In his classic work of lithic scrying, The Writing of Stones, Roger Caillois suggests that the pareidoliac’s interpretation of a stone’s pattern depends upon her own personal internalized database of stored images, a database defined by the cultural stock of mediated imagery forged and embellished by personal memory, emotion and psychical topography. For Caillois, “the vision the eye records is always impoverished and uncertain. Imagination fills it with the treasures of memory and knowledge.”

–Paul Prudence (https://www.transphormetic.com/Essays-in-Print)

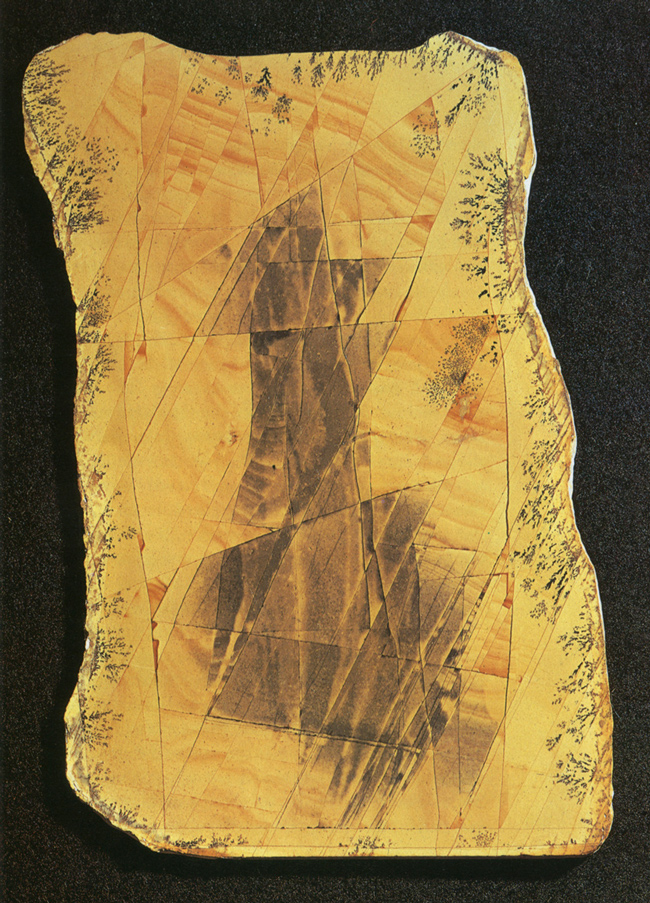

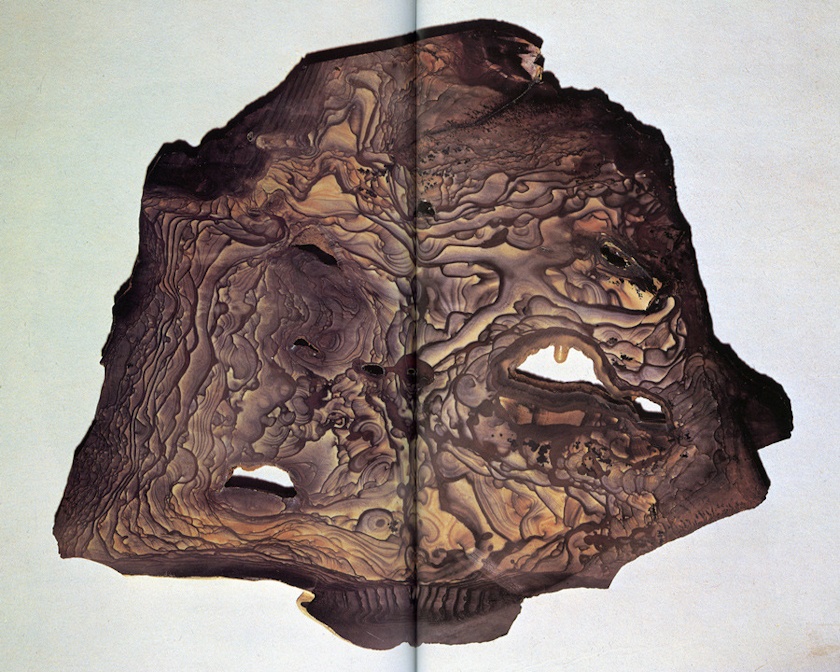

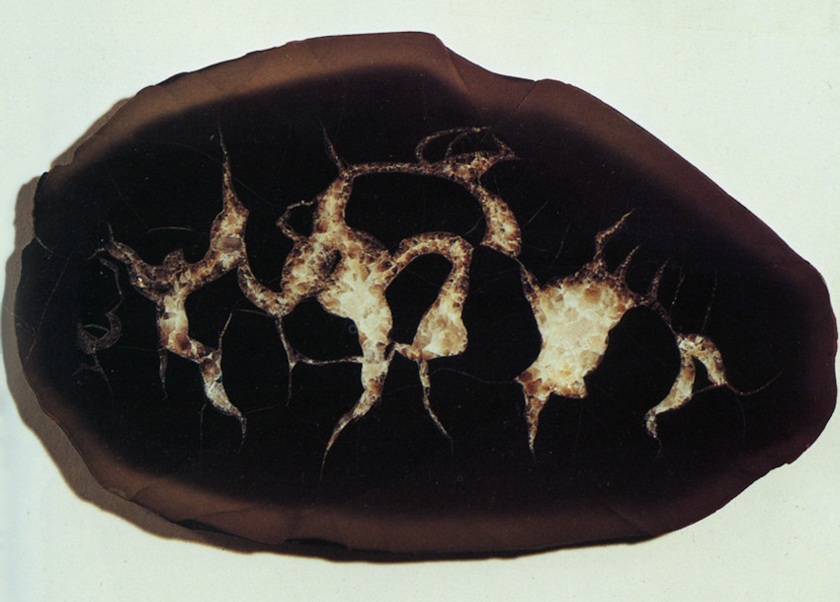

Caillois’ The Writing of Stones (1985) is out of print and costs a LOT. Part of his collection of rock specimens was exhibited at the 2013 Venice Biennale, and they are bewitching:

Caillois was also drawn to the ways in which stones seemed to provoke an imaginative response in humans which in some way made them difficult to conform to strict systems of classification. Caillois’ writings on stone are nourished by the lyrical tendencies of natural histories which reflect the wonder and confusion of classical and early modern scholars in the face of the hallucinatory pictographic forms of stones and their convergence of the brutal, energetic laws of nature with the play of chance. Throughout Stones, Caillois reveals his love of these kinds of paradoxes, defining stones as a ubiquitous and yet utterly marvelous phenomena. He explores how, through history, stones have fascinated human minds with their host of ambiguities, seeming at once animate and inanimate, organic and inorganic, mineral and vegetal, useful and useless, the stuff of poetic reverie and cultural symbolism as well as raw material, the access to which marks the technological advance of human civilization. Stones for Caillois are both an ancient source of human ingenuity and unchained imagination, both finalized by accident during some inhumanly distant epoch and forged according to certain inflexible laws of nature.

–Donna Roberts, An Introduction to Caillois’ Stones & Other Texts

(https://sensatejournal.com/an-introduction-to-caillois-stones-other-texts/)

Caillois himself, from The Writing of Stones:

Stones possess a kind of gravitas, something ultimate and unchanging, something that will never perish or else has already done so. They attract through intrinsic, infallible, immediate beauty, answerable or no one, necessarily perfect yet excluding the idea of perfection in order to exclude approximation, error, and excess. This spontaneous beauty thus precedes and goes beyond the actual notion of beauty, of which it is at once the promise and the foundation

…

Just as men have always sought after precious stones, so they have always prized curious ones, those that catch the attention through some anomaly of form, some suggestive oddity of color or pattern. Stones possess a kind of gravitas, something ultimate and unchanging, something that will never perish or else has already done so. They act through an intrinsic, infallible, immediate beauty, answerable to no one, necessarily perfect yet excluding the idea of perfection in order to exclude approximation, error, and excess. This spontaneous beauty thus precedes and goes beyond the actual notion of beauty, of which it is at once the promise and the foundation.

…

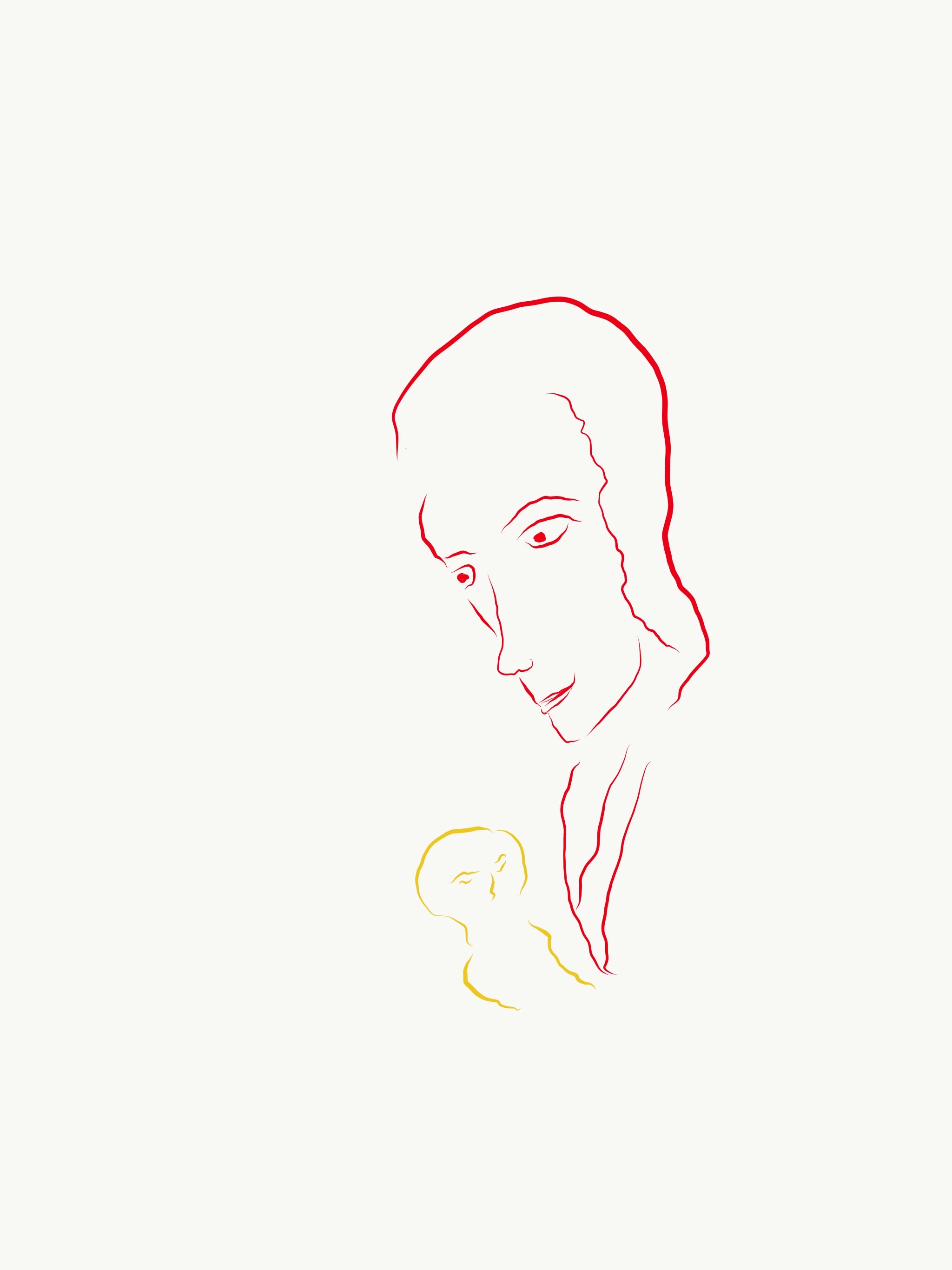

The vision the eye records is always impoverished and uncertain. Imagination fills it out with the treasures of memory and knowledge with all that is put at its disposal by experience, culture and history, not to mention what the imagination itself may, if necessary, invent or dream. So the imagination is never at a loss when it comes to making something rich and compelling out of a subject that might almost seem an absence of all life and significance. »

…

A stone represents obvious achievement yet one arrived at without invention, skill or industry, or anything else that would make it a work in the human sense of the word, much less a work of art. The work comes later, as does art, but the far-off roots and hidden models of both lie in the obscure yet irresistible suggestions in nature. These are subtle and ambiguous signals, reminding us, through all sorts of filters and obstacles, that there must be a pre-existing general beauty vaster than that perceived by human intuition, a beauty in which man delights and which, in his turn, he is proud to create. Stones – as well as roots, shells and wings and every other cipher and construction in nature – help to give us an idea of the proportions and laws of that general beauty about which we can only conjecture.

And Caillois in an article in Diogenes, Vol. 52, Issue 3:

I speak of stones that have always lain out in the open or sleep in their lair and the dark night of the seam. They hold no interest for the archaeologist, artist or diamond-cutter. No one made palaces, statues, jewels from them; or dams, ramparts, tombs. They are neither useful nor famous. They do not sparkle in any ring, any diadem. They do not publicize lists of victories, laws of Empire, carved in ineffable characters. Neither boundaries nor memorials, yet exposed to the elements, but without honour or veneration, they are witnesses only to themselves.

Architecture, sculpture, intaglio, mosaic, jewellery have made nothing of them. They belong to the planet’s beginnings, have sometimes come from another star. So they bear upon themselves the distortion of space like the stigmata of their terrible descent. They come from a time before humans; and when humans came, they did not leave on them the mark of their art or their industry. They did not work them, intending them for some trivial, luxury or historic use. They perpetuate only their own memory.

They are not carved in the effigy of anyone, man, beast or fable. The only tools they have known are those that were used to uncover them; the hammer to reveal their latent geometry, the grindstone to display their grain or awaken their dull colours. They have remained what they were, sometimes fresher, more legible, but always in their truth: themselves and nothing else.

I speak of stones that nothing has ever changed except the violence of tectonic crushing and the slow erosion that began with time, with them. I speak of gems before cutting, of nuggets before smelting, of the hard frost of crystals before the stone-cutter gets to work.

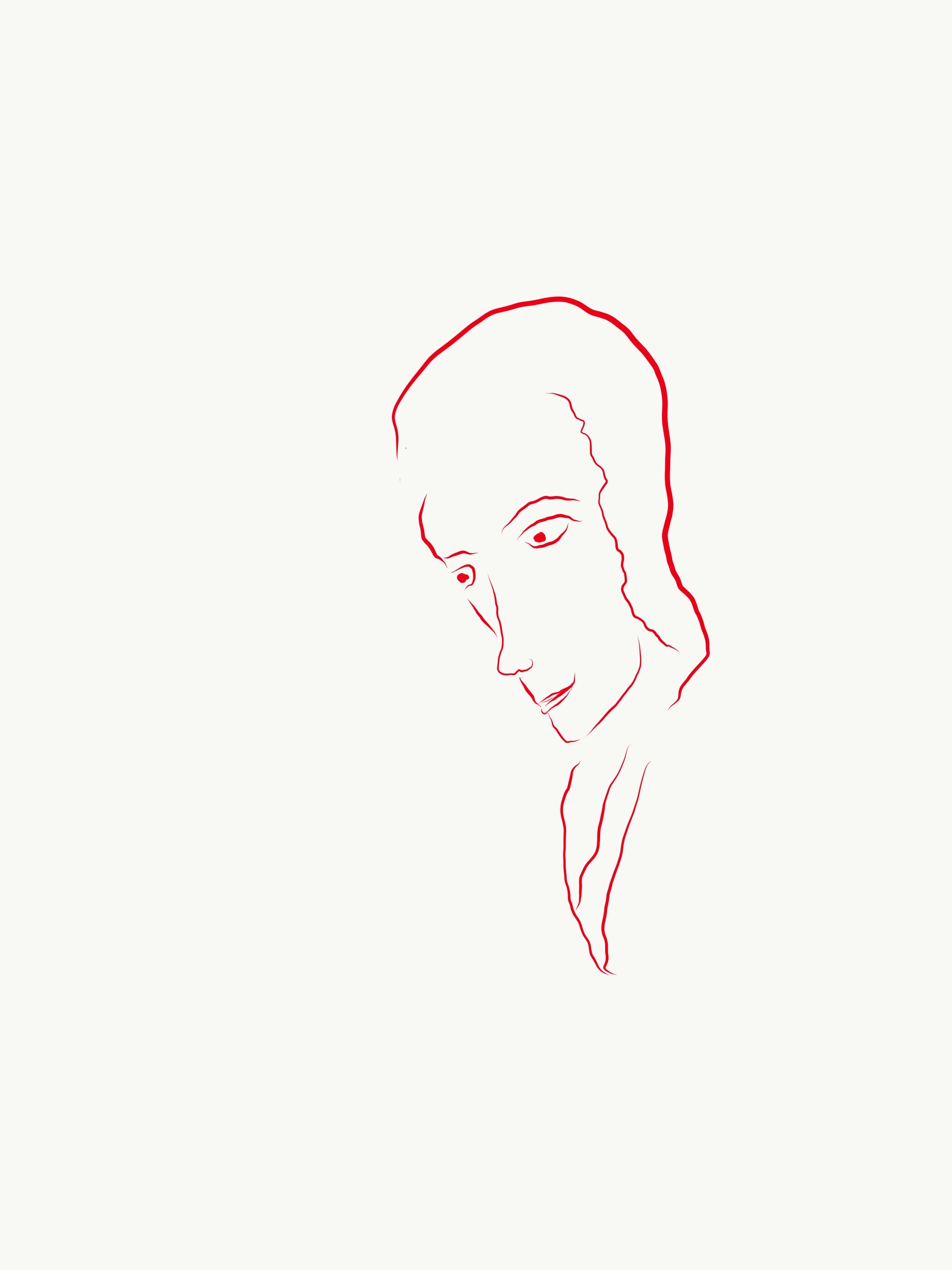

I speak of stones: algebra, vertigo and order; of stones, anthems and staggered rows, of stones, darts and corollas, dream’s margin, ferment and image; of this stone curtain of hair opaque and straight like the locks of a drowned woman, but which does not flow down any temple where in a blue canal a sap becomes more visible and more vulnerable; of these stones uncrumpled paper, incombustible and sprinkled with uncertain sparks; or the most watertight vase where there dances and finds its level again behind the only absolute walls a liquid before water, to preserve which a series of miracles was needed.

I speak of stones older than life that remain after it on cooling planets, when it was fortunate enough to unfold there. I speak of the stones that do not even have to await death…