So here it is, the beginning of November. A lot of work in /lexicon and /lifebox, and at the moment it’s not clear what the blog is doing, beyond helping me remember where I’ve put stuff. I may return to thinking of it as a way to keep like-minded others (whoever they might be) updated with my doings and discoveries and curiosities, but I have no idea if there’s anybody out there …

Category Archives: lexicon

Morning Rabbit Holes

A summary of morning encounters:

- in the parlance of our time

- Filboid Studge

- geniza(h)

- to wake a lexicographer

…which does surface the eclectic side of my …mind

on the Lexicon account

I’ve started to build oook.info/lexicon/ to contain the project that I’ve been gathering material for at oook.info/etc/lexicon.html. I expect it will summarize a sprawling domain of explorations, just right for a winter month.

so that I can find them again

and

harvest of links for February 2025

and

beginnings of the Lexicon Project (a workspace/logfile for a current enthusiasm)

and

On Being Led Astray (something that’s likely to happen multiply in any day)

A London Review of Books post this morning points to Michael Wood’s Quashed Quotatoes (Vol. 32 No. 24 16 December 2010) and carries me off into

…Joyce alludes to Carroll, then, but already had much of his own method. It’s worth pausing over the similarities and differences between the two writers, because we may understand the difficulty of Joyce’s work better if we do — understand it better, that is, rather than diminish it. Both Carroll and Joyce are interested in puns as forms of criticism of behaviour, even portraits of behaviour’s secret life. When we learn in Alice of a school where the pupils are taught ‘Reeling and Writhing … and then the different branches of Arithmetic — Ambition, Distraction, Uglification and Derision, we quickly translate the terms back into their ordinary classroom relatives, and then realise we shouldn’t be translating at all: it’s in their immediate, literal forms that an education is being identified…

…Carroll has a taste for sheer absurdity, the collapse or travesty of plausible meaning, whereas Joyce, as far as I can tell, wants only to multiply meanings, and believes they will never end. We might miss a few, or a lot, and he himself might not always know what they are. But they’ll be there, and some day someone will find them…

…And when Joyce recites the names of days, they too sound like many days we’ve known: ‘moanday, tearsday, wailsday, thumpsday, frightday, shatterday’. Sunday is safe for the moment; safe because unmentioned. Sometimes the transpositions are even simpler, like ‘while the sin was shining’, ‘sneeze out a likelihood’, ‘call a spate a spate’, ‘whirled without end’, or ‘the late cemented Mr T.M. Finnegan’…

…A person who has been given bits of greenery for her birthday instead of the colourful flowers she was hoping for decides to make the best of things. She says: ‘With fronds like these, who needs anemones?’…

…John Bishop, for example, says ‘the only way not to enjoy Finnegans Wake is to expect that one has to plod through it word by word making sense of everything in linear order.’ This is a brave claim, but it is true that the book is hard not to enjoy — it’s just even harder to cope with one’s bewilderment…

…’Our task,’ Kitcher says,’‘is to find a set of readings … that produce an illuminating pattern on the kaleidoscope — where the reader sets the standard for what counts as illuminating.’ …

…semantics are where most of the wordplay is, and the syntax is what provides (the appearance of) a logical structure. Joyce hints at this situation when he writes of his ‘iridated lingo’ as ‘basically English’, suggesting it’s about as far from Basic English as it could get but still thoroughly English in its basic structure. David Greetham, citing this passage, says this is how Finnegans Wake can ‘fill the reader with ideas without making every idea distinct and separable’. I have no real sense of what it means to say, ‘It’s an allavalonche that blows nopussy food,’ but I can recognise the mockery of a proverb — no, the mockery of the tiresome use of a proverb &mdash when I hear it, and it’s the syntax that allows me to do this. Apart from that we can agree that an avalanche would be a hell of a lunch, and a suitable end to a jibberweek…

…We are not only or always laughing as we attend to Finnegans Wake, but laughter is never far away. The text indulges our taste for renegade readings as well as for literal ones, and the revolt against single sense represented by every pun. But even as we revolt, and congratulate ourselves on our acrobatic associative life, something else inside the laughter, something like laughter at laughter, suggests that we may not like disorder as much as we pretend to, and that there is usually more mess in the offing than we can quite see, especially when, as in Finnegans Wake, it’s all ‘quashed quotatoes’ and ‘messes of mottage’.

What a day. And it’s only 9 AM.

on the Whimsy account

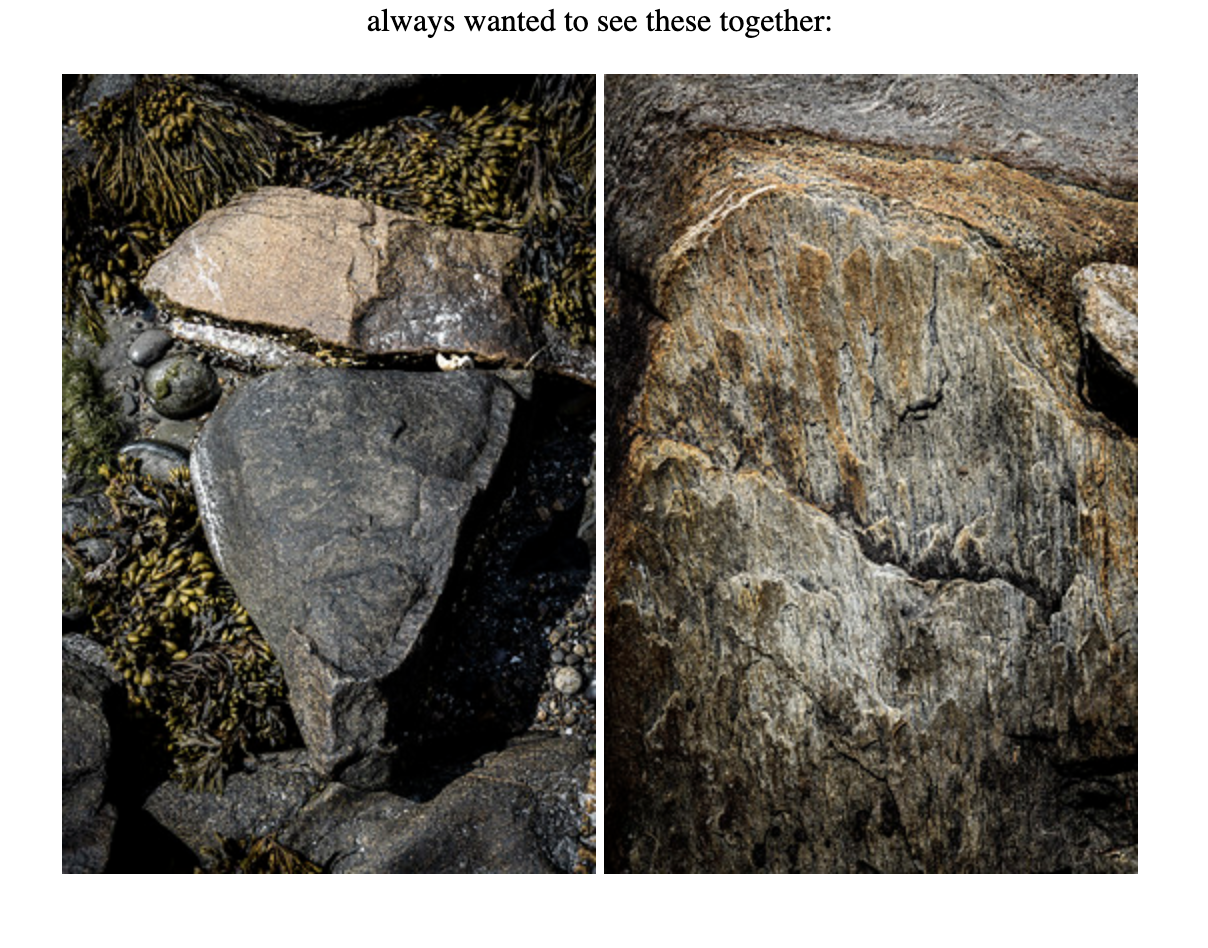

As I begin to work on my Artist Statement for the mid-September Joint Show, I find myself trying to account for the whimsicality of most of my images. So here’s an preliminary summary of my take on Whimsy:

where things are built that cock snooks at

conventional boundaries of the factual.

The whimsical rests upon

risible analogies,

wordplay,

and a fine sense for the absurd.

Visible manifestations of the whimsical

are frequently paredoliac (“…it looks like…”),

often grandiose (what can I conjure out of this rock?),

and are generally calculated to amuse

(think Grandville)

or sometimes to warn and admonish

(think Gargoyles).

The whimsical is likelier to elicit a snort than a guffaw.

But it is wise to remember

that some folk are annoyed by the whimsical,

and that the most literal-minded are often simply baffled.

So choose your audience mindfully

and avoid poking the bear.

Obscure Sorrows

John Koenig’s Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows arrived earlier in the week, and I’ve been enjoying it bit by bit. Here’s an entry that seems to fit with the ambient querilosity of the present moment:

LUMUS: the poignant humanness beneath the spectacle of society

Your culture never really leaves you. Its rhythms are encoded in your heartbeat, its music embedded in the sound of your voice. Its images make up the raw material of your wildest dreams, your deepest fears, even your attempts to rebel against it. So it’s hard not to get swept up in the spectacle of it all, absorbing its stories and values and symbols until you no longer question their importance. It’s as if there’s a circus wheeling around you all the time, so overwhelming that you keep forgetting it’s there.

But there are still moments when you manage to tune out the fanfare—taking time in nature, in solitude, or in some other culture entirely—getting away long enough so that when you return to normal life again, you’re able to look around with fresh eyes, and see how abnormal it really is.

You take in all the scenes and sideshows happening around you. It doesn’t quite feel like reality anymore, more like the worldbuilding of a fantasy novel. You have no idea who came up with this stuff, but you can’t help but be impressed by their tireless dedication to fleshing out even the most mundane details. The vaunted marble halls of politics and business and religion and the arts, each buttressed by its own rules and standards and practices, booming with the echoes of a billion conversations that everyone seems to take so very seriously. Rituals of status and fashion, the mythology of the markets, pop-culture think pieces, and waves upon waves of breaking news. You wonder how you ever managed to get so invested, following all these stock characters, and all their little dramas and debates. Who said what to whom? What does it all mean? What will happen next?

You’re struck by how arbitrary and provisional it all feels. Though it has the weight of reality, you know it could just as easily have been something else. You realize that all of our big ideas and sacred institutions were designed and built by ordinary human beings, soft-bellied mammals, who shiver when they’re cold, dance around when they have to pee, and lash out when they feel powerless. So much of our culture exists because someone was hungry once, someone was bored, someone was afraid, someone wanted to impress a mate, prove something wrong, or leave their kids a better life.

The circus is so big and bright and loud, it’s easy to believe that there’s the real world and you live somewhere outside it. But beneath all these constructed ideals, there is a darker heart of normalcy, a humble humanness, that powers the whole thing. We’re all just people. We go to work and play our roles as best we can, spinning our tales and performing our tricks, but then we take off our makeup and go home, where we carry on with our real lives. None of us really knows what is happening, what we’re doing, where we’re going, or why. Still we carry on, doing what we can to get through it. Even the roar of the city can sometimes feel like a cry for help.

Inevitably, within a few days or weeks at most, you’ll find yourself getting swept right back into the big show, even though you know it’s all just an act. That’s perhaps the most amazing thing about a society: even if none of us fully believes in it, we’re all willing to come together and pretend we do, doing our part to hold up the tent. If only so we can shut out the darkness for a little while, and offer each other the luxury of thinking that little things matter a great deal.

We know it’s all so silly and meaningless, and yet we’re still here, holding our breath together, waiting to see what happens next. And tomorrow, we’ll put ourselves out there and do it all again. The show must go on.

made of decayed organic matter]

If I was teaching Intro Anthropology, or Advanced Anthropology either too, I might use this passage as the Kickoff.

How the Mind works when left to Its Own Devices

I awoke thinking about Material and Immaterial Touchstones, and about Touchstones as property, as fungible, as shareable.

Becoming slightly more lucid, after first sips of coffee, I wondered why would it occur to my semi-waking mind to even consider Touchstones as legal entities, as assignable property? Aren’t they imagine-ary? Creations/creatures of the mind?

And by then fully awake, I realized that Touchstones are ways that the mind notes and labels Significance, such that one can make a mental map of things that matter, tantamount to personal wampeters

Reminder from Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle (1963):

a wampeter is the pivot of a karass,

“a central element around which a karass

is formed, which can be practically anything:

a tree, a rock, an animal, an idea,

a book, a melody, the Holy Grail”

And just to remind anyone not with the Program already,

a karass is “a network or group of people

linked in a cosmically significant manner,

even when superficial linkages are

not evident”

A quick Google search for ‘karass’ gets 225,000 results, of which the third is my own 2004 explication, which is a subpart of something I wrote 16 years ago to the bloody DAY, and still find a clear and relevant summary, despite a few rotten hyperlinks! YCMTSU, folks.

in the parlance of our time

As I recently commented to a friend via email, I’m realizing that I enjoy, indeed revel in, a broad interpretation of ‘folkloric’ which takes in “the parlance of our time” (Lebowski reference) in all its guises.

Among the tools at my fingertips:

- Roger’s Profanisaurus Rex (“the King of swearing dictionaries”) (see 5. Book Review if you dare: “…an indispensable work of reference for students of contemporary linguistics, socio-cultural commentators and dockers who have just hit their thumb with a hammer.”)

- Green’s Dictionary of Slang in its digital edition (“Five hundred years of the vulgar tongue. ‘Quite simply the best historical dictionary of English slang there is, ever has been […] or is ever likely to be’.”)

- Expletive Deleted: A Good Look at Bad Language

- The F Word

- Barrelhouse Words: A Blues Dialect Dictionary

- Dent’s Modern Tribes: The Secret Languages of Britain

- Speaking American: How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk: A Visual Guide

…and others re: various dialects of English.

(for more on parlance, see In the parlance of our time and Repetition in The Big Lebowski)

wordery

The first thing out of the gate in my RSS feed this morning was a pointer to www.thisworddoesnotexist.com/:

deuteroire

1. a legal document giving instructions concerning the legal rights and duties of a deceased person “he signed the first deuteroire for this subject”

2. a word that does not exist; it was invented, defined and used by a machine learning algorithm.epimotor

1. relating to a mental process or the rate at which they develop from peripheral attachment to the cortex or nervous system “epimotor neuron activity”

2. a word that does not exist; it was invented, defined and used by a machine learning algorithm.Link / New word / Write your own

Hm. I thought. The scrabble/clabbers player in the family will be amused.

And then I picked up the book that arrived yesterday, All That Is Evident Is Suspect: Readings from the Oulipo: 1963 – 2018 (Ian Monk and Daniel Levin Becker) and found this in Jacques Duchateau’s “Lecture on the Oulipo at Cerisy-la-Salle, 1963“:

…if all literature contains artifice, since artifice can be mechanized, at least in theory, does this mean that literature in turn can be mechanized as well? Literature and machines has a bad ring to it, it even sounds, a priori, perfectly contradictory. Literature means liberty; machines are syonymous with determinism. But not all machines are the kind that dispense train tickets or mint lozenges. The essential characteristic of machines that interests us is not the quality of being determined but that of being organized. Organized means that a given piece of information will be processed, that all possibilities of this piece of information will be examined systematically in light of a model given by man or by another machine, a machine whose model can be furnished by still a third machine, one whose model etc. etc.

…In the OuLiPo, we have chosen to work with machines, which is to say we are prompted to ask ourselves questions about these notions of structure. This is not new. Writers have always used structures…. From a structuralist perspective, shall we say, all that is evident is suspect. Those forms that are relatively general, accepted by all, and modeled by experience can conceal infra-forms. A systematic re-questioning is necessary to uncover them. A re-questioning which will lead, beyond the discovery of subadjacent forms, to the invention of new ones… (pp 15, 16)

So 55+ years between those two, exactly the time in which my own sentience has been firing on all cylinders, which I might date from my first introduction to hands-on with computers and lexicon, via awareness of Phil Stone’s General Inquirer project (a used copy of General Inquirer: A Computer Approach to Content Analysis [1966] duly ordered…)

…which is of course part and parcel of my lifelong engagement with words and word play. One of the early examples that squirted out when I began to inquire of the Mind for instances:

So she went into the garden to cut a cabbage leaf, [for] to make an apple pie; and at the same time [coming down out of the woods] a great she-bear /coming up the street/, pops its head into the shop. ‘What! no soap?’ So he died, and she [buried him and] very imprudently married the barber; and there were present the Picninnies, and the Joblillies, and the Garyulies, and the grand Panjandrum himself, with little round button at /the/ top; and they all fell to playing the game of catch as catch can, till the gunpowder ran out at the heels of their boots.

([my version] /not my version/)

(see here for the marvelous backstory)

which my brother John quoted to me when I was 5 or 6, and I took to mind… along with many other snatchets of verse and balladry, from John and from records in the family library. My engagement with Ogden Nash and Edith Sitwell and Tom Lehrer all spring from the same font of lexical foolishment, and Archy and Mehitabel and of course Pogo are other ur-text examples. More will doubtless surface as the day progresses.