Big whorls have little whorls

Which feed on their velocity,

And little whorls have lesser whorls

And so on to viscosity.

–Lewis F Richardson, who “…studied fluid turbulence

by throwing a sack of white parsnips into the Cape Cod Canal.”

(quoted in James Gleick, Chaos: Making a New Science)

The day began with a by-chance glance at a short piece in the May-June Harvard Magazine, “Will Truth Prevail?” by Drew Pendergrass ’20, which takes off from the author’s reading of Edward Lorenz‘ 1963 article and included this:

How do we find the signal in the noise? Climate science is based on the observation that even though everyday weather is chaotic and can be predicted only a few days ahead of time, the weather in aggregate is much easier to handle… Climate, governed by the slow warming and cooling of the oceans with the seasons, follows different rules than weather does…

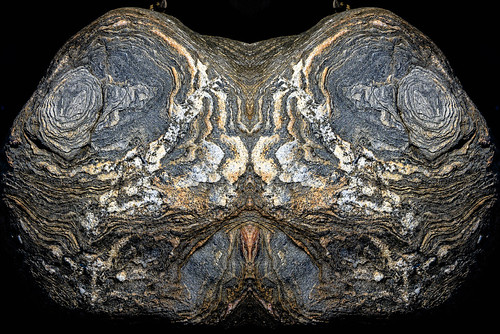

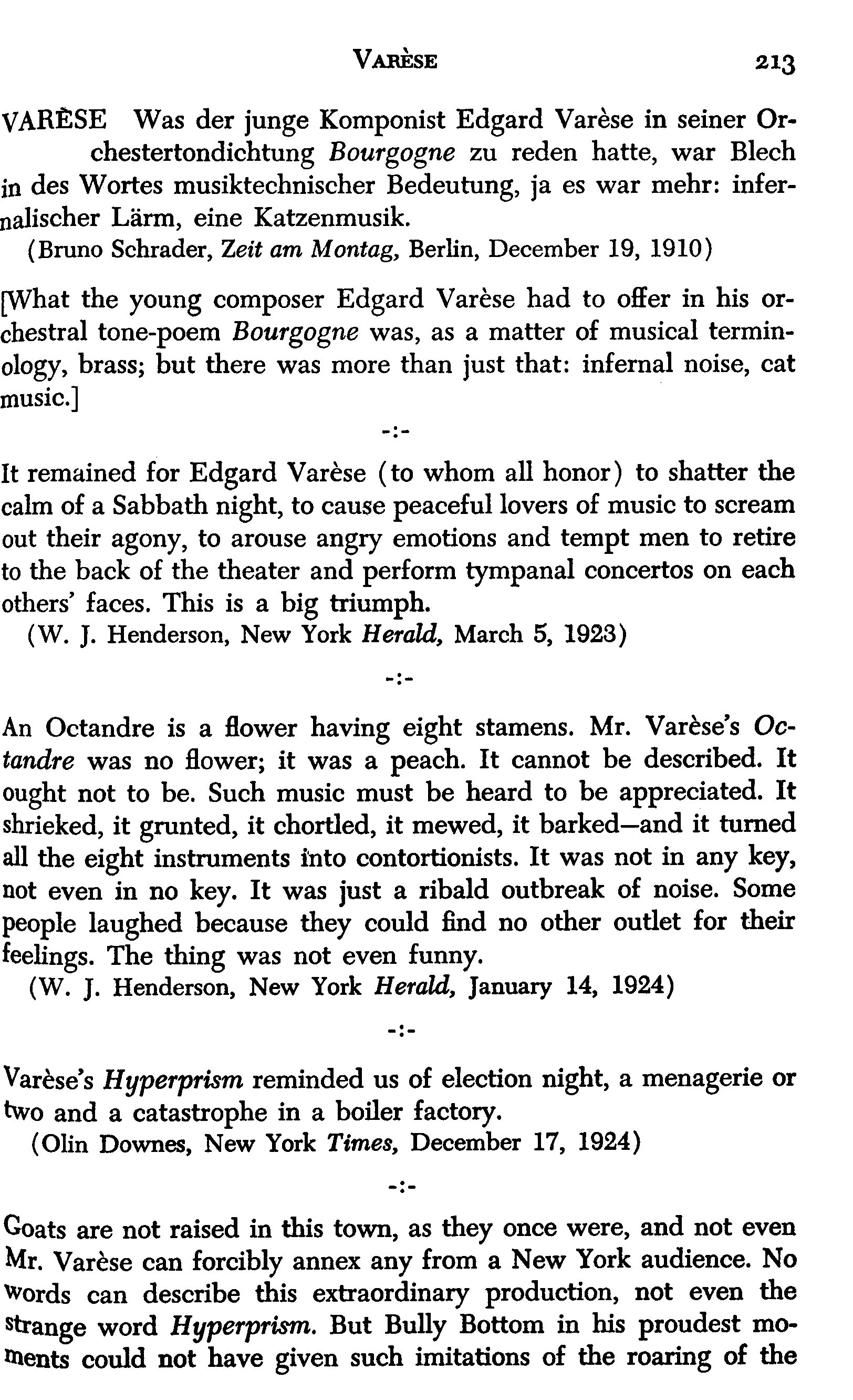

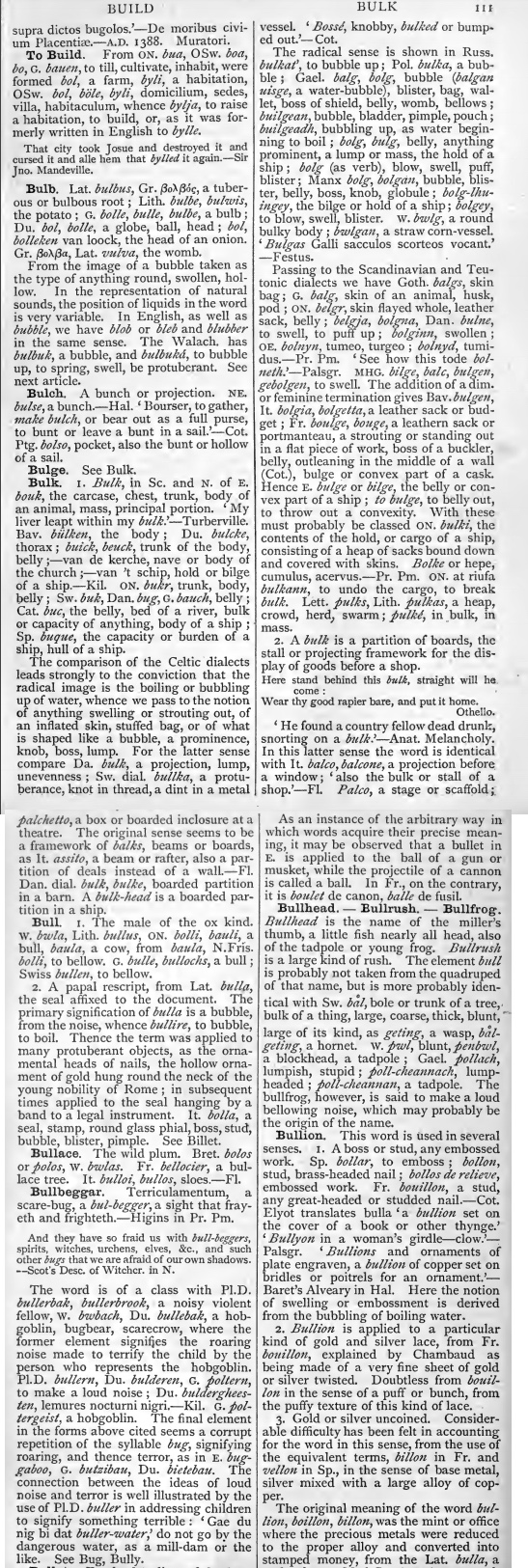

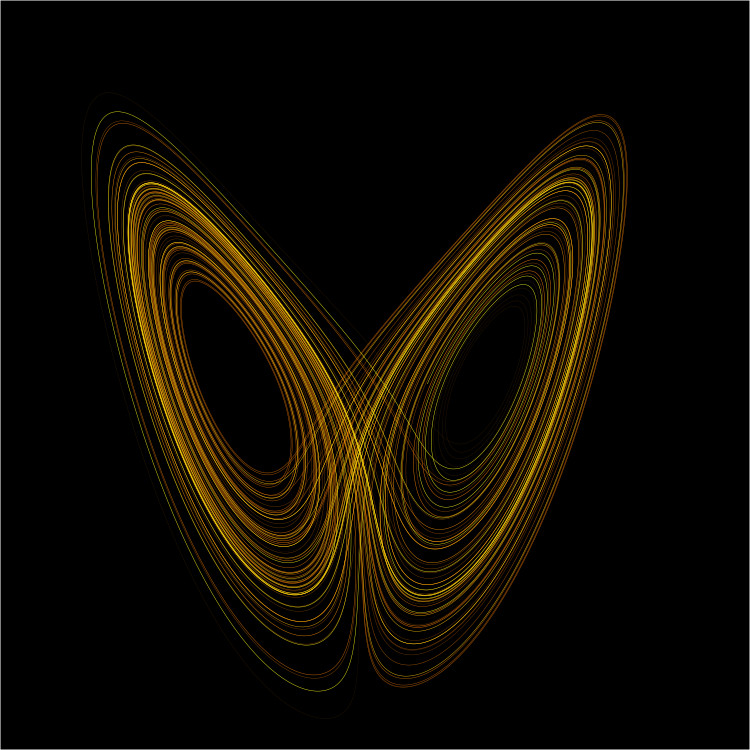

The article included a familiar image:

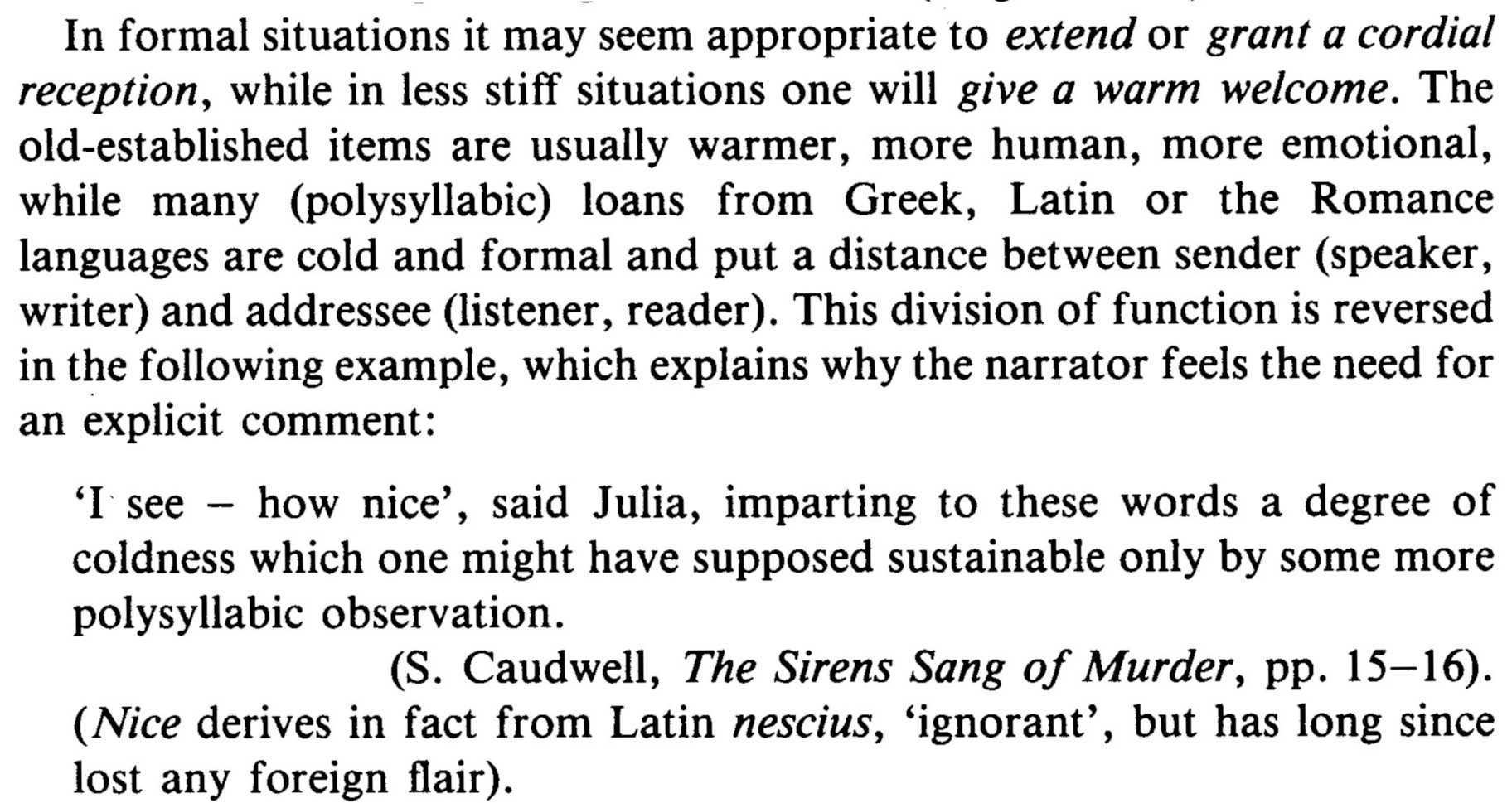

(By User:Wikimol, User:Dschwen – Own work based on images Image:Lorenz system r28 s10 b2-6666.png by User:Wikimol and Image:Lorenz attractor.svg by User:Dschwen, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link)

Another bit of the unexpected came in this morning via one of the blogs I follow:

something truly special is happening in the Southern Hemisphere: The air high above the Southern Ocean and Antarctica, anywhere between 20–40 kilometres (12–25 miles) above the surface, is warming a lot in just a few weeks… a “vortex breakdown” or “Stratospheric Sudden Warming”, and in the Southern Hemisphere it only happens for the second time that we know of, and certainly since the era of satellite measurements began in the late 1970s. The first time was in 2002… during Sudden Warmings, as their name suggests, the stratosphere over the pole warms a lot — by about 50 degrees celsius over just a few days… After the one previous event in the Southern Hemisphere, the entire following summer saw drier and warmer weather than usual in Southeastern Australia. We expect something similar to happen this year. Southeastern Australia is already experiencing a drought, and yet another dry and hot spring and summer could be devastating. (Martin Jucker)

Remembering that James Gleick’s Chaos had a whole section (pp 121-153) on “Strange Attractors” and that I’d never quite wrapped my mind around what it was that Lorenz kicked off in the 1963 paper, I got Gleick from the shelf and decided to try again, but first made a quick stop in the Wikipedia ‘Attractor’ article:

an attractor is a set of numerical values toward which a system tends to evolve, for a wide variety of starting conditions of the system

…A dynamical system is generally described by one or more differential or difference equations. The equations of a given dynamical system specify its behavior over any given short period of time. To determine the system’s behavior for a longer period, it is often necessary to integrate the equations, either through analytical means or through iteration, often with the aid of computers… The subset of the phase space of the dynamical system corresponding to the typical behavior is the attractor…

An attractor is called strange if it has a fractal structure. This is often the case when the dynamics on it are chaotic, but strange nonchaotic attractors also exist. If a strange attractor is chaotic, exhibiting sensitive dependence on initial conditions, then any two arbitrarily close alternative initial points on the attractor, after any of various numbers of iterations, will lead to points that are arbitrarily far apart (subject to the confines of the attractor), and after any of various other numbers of iterations will lead to points that are arbitrarily close together. Thus a dynamic system with a chaotic attractor is locally unstable yet globally stable: once some sequences have entered the attractor, nearby points diverge from one another but never depart from the attractor.

OK, just barely holding on here. It’s helpful to recognize that a not-strange attractor is exemplified by the phase space of a pendulum, which swings across a point at which it finally stops when its energies are dissipated. A dynamical system with many variables (dimensions) in play (that is, changing and being changed by one another) has a vastly more complex phase space. Gleick:

Every piece of a dynamical system that can move independently is another variable, another degree of freedom. Every degree of freedom requires another dimension in phase space, to make sure that a single point contains enough information to determine the state of the system uniquely… Mathematicians had to accept the fact that systems with infinitely many degees of freedom — untrammeled nature expressing itself in a turbulent waterfall or an unpredictable bra (in — required a phase space of infinite dimensions. (pp 135-137)

Gleick’s Chaos came out in 1987, and my friend Ron Nigh photocopied it and sent it to me, saying that it was the most mind-bending book he’d encountered in years. I duly read what I could grasp of it and was suitably impressed but still somewhat nonplussed. Other books that belong to the same state of personal nonplusment [knowing that what one is reading is really important but not necessarily assimilating the contents…] are Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel Escher Bach, Ann Berthoff’s Mysterious Barricades: Language and Its Limits, and David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years.

And that was only part of the day…