Category Archives: musics

Jesse Welles

I discovered this remarkable artist only yesterday, which says something about how isolated I am (he’s been around for several years, but active on TicToc [of which I’m not a follower] apparently in recent years. Here’s my collection of YouTube videos, the lyrics of which speak very eloquently to these parlous times.

Links in the /musics directory

Again a bit of a rescue operation, a page to make accessible various documents buried on oook.info, and to inspire me to update access to musics materials.

Summer

So what happened to June and July? A strange summer, mostly unseasonably cool and foggy here in midcoast Maine, while sweltering ‘most everywhere else (fires, plagues of frogs, rain and more rain…). I put a lot of time and effort into four Convivium Questions:

- Words To Live By last of May 2023

- realizing the Beautiful, from adversity early June (Brian’s Question)

- on Community early July (John’s Question)

- And what next? mid July

…which l enjoyed working on but can’t really claim had any useful effect beyond my own sorting out of what I was inspired to discover and put into words, and of course plentiful Collection Development by way of book purchases to salve arising curiosities.

In photographic realms, just a few Flickr Albums generated, but no new ground broken by way of image projects, and no public display lined up until maybe next spring. I have ideas for Blurb books, but nothing underway. I now have the wherewithal to make good scans of a lot of old negatives from 40-50-60 years ago, and those might feed into books too.

And in musical realms, I continue to play for an audience of one, and to acquire irresistible new-old instruments via Jake Wildwood, but Betsy is of the opinion that there are Too Many instruments, so there’s a plan afoot to recycle some of the rarely-played via Jake.

Otherwise, the rapidly-approaching 80th birthday is beginning to loom…

and so Buxtehude

One of the pleasures/trials/challenges of advancing age is the occasional experience of finding oneself faintly ridiculous. Sometimes it’s a consequence of some quest or quixotrie one has embarked upon, some exercise in futility or overweening bumptiousness which has turned out to be vastly more complicated and complex than one initially anticipated. That’s OK, nobody is watching the clock or running a performance review on your ass, or not yet anyway. Today’s case in point reaches back 20 years, or maybe 75 years.

When brother David (16 years older than myself) was dying, he wanted to hear a particular piece by Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1702) that he had somewhere on 78… a turntable that could handle 78s was quarried and hooked up to bedside amp and speakers, and the 11″ disk was played. David had thousands of records (he was an acoustic engineer, founder of DBX, builder of Earthworks speakers and microphones, audio perfectionist, but not the most orderly of folk), so just finding that one was an adventure in itself.

Lately I’ve been curating my own mountain of vinyl and figuring out how to make the collection(s) more accessible. My solution has been to stick numbers on the albums (around 2500) and photograph their covers, then make web pages with pictures of albums belonging to the (very) various categories, so that I can leaf through the visual catalog and find, for example, a particular obscure Persian ney album, or specific gamelan performance, or Bach chorale, or… and put that prize onto a turntable and step back in time to remember former encounters with the music.

And so the barn now has glorious sound capabilities, analog and Bluetooth digital, downstairs in the Museum and the Shop (Cambridge Soundworks speakers) and upstairs in the Auxiliary Library (Earthworks speakers). I’ve been figuring out how to access and move amongst the various media, including cassette tapes, CDs, mp3s, and streaming Bluetooth services, as well as vinyl and shellac. And while I was sorting and cataloging and tagging, I came across that Buxtehude 78. This morning I woke up wondering if I could play the record through the amps and speakers, and sure enough I exhumed that 78-capable turntable (complete with 78-specific stylus) and the record was playable after 20 years of hibernation.

Next question: could I sort out a pathway from the 78 to a digital recording? In effect, an analog to digital conversion, should be easy. And probably is, if you know what you’re doing or are willing to try a lot of solutions that ought to work …play into a CD writer, or make a cassette tape, or perhaps run the signal from the turntable and through a preamp and then somehow pass that through USB to Audacity editing software on the laptop… It all sounds feasible, given the right connectors and the proper curses to make bits of hardware accessible to one another. But for a lot of good reasons it doesn’t quite work as well as it seems that it should… and that’s what I spent most of the day messing with, learning a lot about paths that didn’t connect and might work if I had the right bit of equipment.

By 4 PM I was at an impasse with connectors and jacks, and was figuring to do other things for a while, and attack the problem again in the morning. I thought maybe I should just see if the interwebs could tell me anything about the 78 record recorded in 1946… so I searched for title and performer (Axel Schiǿtz) and mirabile dictu up came a YouTube video of the exact precise very recording, with none of the surface noise and pops and clicks of the shellac original. I could actually hear the words, and thus have some idea of what brother David heard all those years ago (before there even was vinyl) and kept in his memory all his life. Here it is:

Aperite mihi portas justitiae

Open to Me, Gates of Justice

So the faintly ridiculous part of this was that I didn’t ask Google first, I who generally pride myself on knowing my way around the worlds of Information that I’ve inhabited all my life, and that I’ve kept up with pretty well. I was stuck on the realia of that 78, on the story from David’s last days. But now I have a slightly better understanding of where he was at (Gates of Justice indeed…), what he thought about, and how he responded to the intricately structured sound of a rather obscure Danish/German mid-Baroque musical eminence, as interpreted by an even more obscure Danish singer.

Our UPS dude said to Kate today, “What does your dad do up there in the barn?”. Her answer: “Who the hell knows…”

Facing the Music

I spent quite a bit of the last fortnight wrangling the Question “how about we explore the roles music has played in our lives?” which is for me something between a sheer impossibility and a marvelous opportunity. oook.info/Conviv/musics0.html is the summary collection of pointers that I arrived at, many of them YouTube videos, but a week later I’d probably put up a whole different set. I continue to struggle with how to curate my collections: vinyl, cassette, CD, MP3, video, bibliographic, playlists (mostly Spotify), material from the various iterations of Cross-Cultural Studies in Music, and of course instruments.

of Silence

Yesterday the day began with this advice from Kate:

And support your local bookstore

What actually matters to me includes thinking things through and constructing summaries of the process, perhaps for an audience of one. The blog is a basically harmless venue for such maunderings, and has the advantage of being distributable to any like-minded others out there. So things like this have a home where they can be found again at need:

Wovon man nicht sprechen kann

darüber muß man schweigen

Whereof one cannot speak

Thereof one must remain silent

…which has, among other things, to do with Silence, investigation of which has occupied me for the last couple of days. The subject came up via an eloquent post by Andy Ilachinski, which mentions “the infinite variety of silences that permeate existence” and references Notes on Silence and the accompanying film In Pursuit of Silence. I got and inhaled both.

And so I’ve spent the last couple of days bouncing around in various texts. Herewith some of my findings, each worth lingering over:

SILENCE and LICENSE are anagrams; both are forms of Freedom.

***

People think that their experiences are the reality and in fact, experiences are always interpretation, they’re always a construct. (Ross NS 264)

“Sound imposes a narrative on you and it’s always someone else’s narrative. My experience of silence was like being awake inside a dream I could direct.” (Maria Popova)

***

Any musician will tell you that the most important part of playing a piece of music, especially classical music, is the rests, the silences. (NS 276)

Louis Armstrong maintained that the important notes were the ones he didn’t play. (Popova)

***

“you are confronted with your inner noise, with your inner resistances.” (Sturtewagen NS 161)

“…persistent self-noise of the internal sort… ‘the interminable fizz of anxious thoughts or the self-regarding monologue’.” (Shen NS 207)

***

“I think it’s hard for us in the West to see silence as an end in itself… We think of silence as an absence and something negative…

Silence is like a rest in a piece of music—it’s not blank space, it’s a concrete space that’s filled with something other than words. (Pico Iyer NS 123)

***

“…as simple as shifting your attention from the things that cause noise in your life to the vast interior spaciousness which is our natural silence… the process of ungrasping, the process of opening your hand, of unclenching the fist…” (Ross IPS)

***

In a world of movement, stillness has become the great luxury. And in the world of distraction, it’s attention we’re hungering for. And in a world of noise silence calls us like a beautiful piece of music on the far side of the mountains. (Pico Iyer, IPS)

***

“Silence is a sound, a sound with many qualities… Silence is one of the loudest sounds and the heaviest sounds that you’re ever likely to hear.” (Evelyn Glennie)

***

“Modern people don’t feel moved or impressed just by living. In order to do so, we need to keep the silence and examine ourselves.” (Roshi Gensho Hozumi IPS)

Give up haste and activity. Close your mouth. Only then will you comprehend the spirit of Tâo. (Lao-tzu)

I also took this opportunity to reacquaint myself with R. Murray Schafer’s The Tuning of the World (“a pioneering exploration into the past history and present state of the most neglected aspect of our environment: the SOUNDSCAPE”), and to put my perceptual apparatus to work on the soundscape of a 4-mile trash picking up expedition. The sound of car and truck tires on the road was the loudest, most frequent, but still intermittent interruptor of silence; dogs barked at my passing in four places. My own footfalls were the regular punctuation of an otherwise almost entirely silent passage.

Schafer’s chapter on Silence provoked a brief dip into acoustical theory via Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894), whose On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music is a still-relevant exploration of the psychophysics of sound. von Helmholtz distinguished ‘non-periodic vibrations’ as “noise”, distinct from the ‘periodic vibrations’ that characterize music. Others (among them Claude Shannon) developed the notion of signal-to-noise ratio as a measure of the operational health of an information system. Noise is generally formless, seems to carry very little information, is inclined to the random rather than the patterned, and is that which we try to edit out of soundscapes as we pass through them. Anechoic chambers are sound environments that reduce noise to a minimum. John Cage’s description of his experience in such a space

Evelyn Glennie is another wonderful and inspiring re-discovery in the context of silence:

And here’s one of my favorite African music examples, a percussionist’s dream captured as University of Ghana postal workers cancelled stamps.

Earnest & Bogus enter the Time Warp

This bit of brilliance arrived a few days ago: Protobilly: The Minstrel & Tin Pan Alley DNA of Country Music 1892-2017. The Amazon précis:

This 3 CD reissue anthology is the first to track twentieth century American vernacular music of old time country, bluegrass, jazz and blues by tracing their beginnings in 19th century blackface minstrelsy and Tin Pan Alley.

Country Music is a genre driven by songwriting and publishing. This fact alone has given opportunity for songs to be refashioned again and again showcasing stylistic as well as lyrical changes over the past 100 years. The foundation of the American popular songbook traces its beginnings to the Vaudeville, Circus, Minstrel, Music Hall and Theater stages of the mid-late 1800s. The songs spread throughout the country and world creating a new musical tapestry that included both black and white performers of all backgrounds. Their songs and styles are presented in this three CD anthology.

By aligning performances from the earliest cylinder recordings with later 78 rpm, LP and CD versions, PROTOBILLY brings to life 81 historic recordings, more than half never before reissued…

Assembled by collectors and music scholars Henry Sapoznik, Dick Spottswood, David Giovannoni, and Dom Flemmons, this wowed me from the first cuts. I hadn’t realized that those Edison cylinders (and other brands too) had any relevance to the music recorded in the 78 era, or that the material captured in cylinder recordings had itself a considerable pedigree in sheet music and mid-19th century stage performance. Dom Flemmons puts it beautifully:

…songwriters, black and white, performed in the streets, theaters, music halls, medicine shows and circuses of a budding America reimagining the American Dream through song. The songs reflected and exaggerated the social climate of the world at that time. Like the internet memes of the digital era, Tin Pan Alley was not limited to unapologetically featuring songs that included ethnic humor lampooning working class people whether they be Irish, Italian, Jewish, German, African-American or Asian-American for the amusement of a paying audience. But it would be blackface minstrelsy, the songs that lampooned African-American experience, that would reach worldwide fame much to the chagrin of modern culture…

Black songsters pull songs of black buffoonery inside out and create humorous toasts of black ingenuity and excellency. Rural hillbilly singers take Broadway harmonies and give them the “high lonesome sound” of the Southern Mountains…

Here’s an example from Protobilly: The Arkansas Traveler seems to be datable as music and text from the 1850s, and was popularized on the vaudeville stage by Mose Case from the 1850s to 1880. There was a piano roll version by 1900, credited to Case. Here are three versions from Protobilly: Len Spencer (Edison cylinder 1902), Jilson Setters (Victor 78RPM 1928), and Clayton McMitchen & His Georgia Wildcats (Crown 78RPM 1932). And here’s a New Lost City Ramblers rendition:

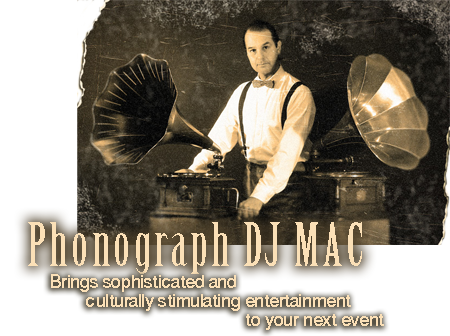

The cylinder recordings I’ve heard before were so scratchy-noisy as to be almost unlistenable. The examples in the Protobilly compilation have been cleaned up beautifully, and I’m inspired to (re-)explore MAC’s (Michael Cumella) Antique Phonograph Music Program on WFMU, which has 23 years of archived programs (see list of artists played in those 23 years). MAC uses antique disk players, so you get a sense of how the original technology sounded to early 20th century ears.

Try this one: Blues My Naughty Sweetie Gives to Me (Esther Walker, 1919)

Spotify offers at least 100 variants of the song. Here are two:

Kweskin Jug Band and Sidney Bechet.

MAC did programs of cylinder recordings as well, with guest collectors. Try this one for a good introduction to cylinder technology (broadcast date April 15, 2003):

E & B update

Earnest and Bogus have been away on a Guitar Heroes and Other Musical Influences field trip, an effort to summarize my own musical history, which remains a subproject “Under Construction” in perpetuity, but has for the moment stabilized enough to feel distributable. I’m plunging back into the larger project of corralling Nacirema musics, but also being diverted into exploration of thousands of downloaded video clips.

Earnest and Bogus’s Big Adventure part 3

“Hm.” I remember thinking. “Need to provide entrée to the collectors who found, preserved, annotated, packaged, released, and loved this music. And to the venues and mass media outlets that brought it to broader publics…” and the more I look into the background, the more stuff I find to explore and include, so more searches get done, more stuff gets ordered and read and heard. Case in point:

Just flew in through the transom: The Harry Smith B-Sides (“the flip side of 78-rpm records that Harry Smith included on the Anthology of American Folk Music”).

Who needs this? Certainly the music-obsessed, those who have grown up with the Anthology (1952, reissued on CDs 2007… and download !!liner notes!!) and its sequelæ Anthology Of American Folk Music Volume 4 (Revenant Records 2000) and The Harry Smith Project: The Anthology Of American Folk Music Revisited (2006), and the lucky few who followed gadaya’s labor of love MY OLD WEIRD AMERICA An exploration of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music blog when it was alive for downloads of the Variations.

The B-Sides are fully as revelatory as the 84 cuts on the original Anthology:

a mirror image of the Anthology… a way to hear the complete statement of each 78RPM disc… as they were originally released in the 1920s and 1930s…

Most people interested by the Smith Anthology will agree that it stands as an esoteric beacon outside the whole dysfunctional culture system. Just like when it was first issued in 1952, you still won’t hear the music of the Smith Anthology on the radio, on TV or on the front pages of the internet…

By releasing his Anthology to the audience of Folkways Records, Harry Smith dropped an extraordinary rural working class culture bomb on a New York City world of artists, bohemians, radicals, and city musicians… (Eli Smith, B-Sides liner notes)

A New York Times story on the B-Sides: How to Handle the Hate in America’s Musical Heritage

The 1927 Bristol recording sessions (the Big Bang of country music) captured 76 songs, recorded by 19 performers or performing groups, including the Carter Family.

The saga of recording Black musicians in the 1920s was somewhat more haphazard. There was a booking agency for the Black vaudeville circuit, the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA, referred to by Ma Rainey as ‘Tough On Black Asses’) that dealt with jazz, comedians, dancers and (mostly female) blues acts (Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith). Country blues artists were mostly too small-time and local for TOBA, and were recorded in studios outside the South (e.g., “Paramount Records, based in Port Washington, Wisconsin. The company was a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company, who also made phonographs…”) but the musicians were recruited by

“field scouts” [used] to seek out new talent, though this is a somewhat grand name for men the likes of HC Speir, who ran stores in the South and simply kept an eye out for local musicians. Through Speir they recorded Tommy Johnson and, most importantly, Charley Patton. It was Patton that took Son House, Willie Brown and Louise Johnson to Paramount’s new studios in Grafton WI in 1930.

Several record companies had catalogs of “Race Records” made for a specifically Black rural public, and it is these disks that were rescued by record collectors in the 1960s.

Thinking about mass media and Nacirema musics, one of the constants for most of the last century has been Grand Ole Opry, which was first broadcast from Nashville in 1925 and came to blanket the rural South with versions of aural and, eventually with TV, visual imagery of regional culture. Separating the authentic and vital from the stereotyped and bogus is challenging, and just how accurate and inclusive the picture was/is/can be argued endlessly. The intrusions of commercial elements are everywhere, and might as well be acknowledged while we hunt for whatever purity they blanket. Resort complexes like Opryland USA and Dollywood and Branson MO and Graceland have drawn crowds seeking ‘authentic’ experiences, and have provided income for entertainers.

The cultural complexity of the Showcase experience is exemplified by Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973), who was a lawyer, performer, researcher, field collector, impresario, and tyrant for the cause of what he spoke of as “mountain music.” His Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville NC (first in 1928) was the paradigm for many other folk festivals.

Lunsford himself despised the commercialism and cultural nonsense he saw in Asheville’s Rhododendron Festival, and opposed the stereotyping of mountain folk as backward and ignorant. Still, as a performer he could produce material as bogus as Good Old Mountain Dew

A documentary on Lunsford, This Appalachian Music Man Lived A Beautiful Life, in which Alan Lomax shows up:

and David Hoffman’s Bluegrass Roots 1965 was filmed in a mountain tour conducted by Lunsford:

John (1867-1948) and Alan (1915-2002) Lomax are giants in the history of discovering and recording Nacirema music in the field. A site from the Musical Geography Project offers maps of Lomax travels. John Szwed’s biography of Alan Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World is excellent, and Duchazeau’s Lomax: Collectors of Folk Songs is a charming graphic-novel portrayal of a 1933 Lomax collecting foray into the South. Among the interesting videos on Alan Lomax:

Cultural Equity has a vast collection of Alan Lomax field materials

Wikipedia lists more than 50 American folk song collectors, and American Folklife Center has a page of women collectors, including Frances Densmore (1867-1957), Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle (1891-1978).

Mike Seeger’s fieldwork in Appalachia brought Dock Boggs (1898-1971) to modern audiences and covered a wide range of southern styles of music and dance. Just Around The Bend: Survival & Revival in Southern Banjo Sounds was his last documentary film, and there are several documentary CDs and DVDs: Close to Home: Old Time Music from Mike Seeger’s Collection, 1952-1967, Mike Seeger Early Southern Guitar Styles, Early Southern Guitar Sounds, Southern Banjo Styles #1 Clawhammer Varieties & more, Southern Banjo Styles #2-Early 2- and 3-Finger Picking, Southern Banjo Sounds, besides his work with the New Lost City Ramblers, his sister Peggy, and various other musicians.

Art Rosenbaum’s Art of Field Recording (1 and 2) (available via Dust to Digital) offers a wealth of field recordings made 1959-2010.

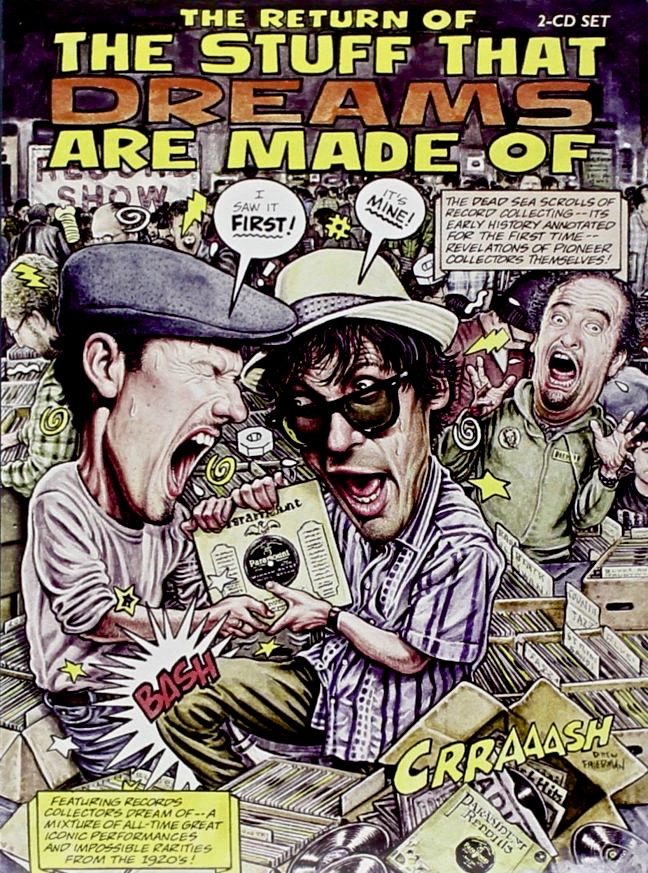

Record collectors inhabit a separate documentary world, well described in Amanda Petrusich’s Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records.

…an intense, competitive, and insular subculture with its own rules and economics—an oddball fraternity of men (and they are almost always men) obsessed with an outmoded technology and the aural rewards it could offer them. Because 78s are remarkably fragile and were sometimes produced in very limited quantities, they’re a finite resource, and the amount of time and effort required to find the coveted ones is astonishing. The maniacal pursuit of rare shellac seemed like an epic treasure hunt, a quest story—an elaburate, multipronged search for a prize that may or may not even exist. (pg. 4)

Among collectors of 78s, Joe Bussard stands out as a National Treasure. A Fretboard Journal profile introduces his rather unique personality:

Joe Bussard has an interesting theory: Musical forms seem to lose their value when the electric bass is introduced. “That goddamn electric bass ruined everything!” he shouts. “I went to Trashville—I mean Nashville—in ’57 to see the Opry, and I asked for my money back, I’ll tell you that right now. They didn’t have shit I wanted to hear. Garbage! When rock come in, I didn’t have any interest in anything that damn dumb! Elvis and all that bullshit! I already knew better than to fall for that, buncha goddam shit for retarded 4-year-old kids!”

but its essence is best appreciated in videos:

Joe has been very open-handed with his collection, making tapes for people and contributing to a vast array of compilations. There’s a video Desperate Man Blues: Discovering the Roots of American Music that I’d love to get my hands on. Looks like I had it in 2007 from Netflix, and I’ve requested it again.

Besides his Fonotone Records recording business which ran for a decade or so and lately produced a remarkable compilation

Massive 5CD set of American Primitive music unearthed for the first time (in various styles: Jug Band, Country, Old Time, Blues and Bluegrass), recorded and documented by Joe Bussard’s 78-RPM Fonotone label, 1956-1969 — not one track previously on CD before. Incredible package featuring 131 tracks over 5 discs, 160-page perfect-bound book, 17 full-color postcards, 3 record label reproductions in souvenir folder and a nickel-plated Fonotone Records bottle opener(!) — all packaged in a deluxe cigar box.

Joe Bussard recorded the young John Fahey in 1959-1960.

John Fahey deserves mention under Collectors for his part in the rediscovery of Bukka White and Skip James (both of whom had made mighty 78s in the 1920s), described in detail in Dance of Death: The Life of John Fahey, American Guitarist, and for the research he did on Charley Patton, and other Revenant Records collections American Primitive, Vol. 1: Raw Pre-War Gospel (1926-36) and American Primitive Vol . 2 – Pre-War Revenants (1897 – 1939).

Fahey’s life was a trainwreck, with occasional bright interludes, and is perhaps best discussed under Guitar Heroes.

The fraternity of collectors is nicely documented via Mainspring Press (“Information and Resources for Historic-Sound Enthusiasts”, including Discographies). Their blogroll provides links to Excavated Shellac (mostly concerned with non-US sources) and Sound of the Hound (“dedicated to the story of how recording came into being and how it conquered the world”). See also Amanda Petrusich on John Heneghan and The Great 78 Project at the Internet Archive.

Some collectors have specialized in “ethnic” 78s (a whole other subset of my musical world), including Dick Spottswood (who grew up near John Fahey) and Ian Nagoski (of Canary Records and Fonotopia) and Karl Signell. See also 78rpm Collector’s Community (“a social network for collectors of 78rpms recordings, phonographs, memorabilia, recording machines and the history of the 78 rpm recording era”)

Experiments with recording at 78 RPM include American Epic (and accompanying CD and book).