I’m trying to pull together the fragments I’ve been sorting and knitting, to (a) summarize what I’ve been working on during the hiatus, and (b) to articulate what that activity has taught me (or is it learned me?) about the past, the present, and possibly the always-murky future. The result amounts to an assessment of who I am, and what it is that I do, and what I have been doing all along.

The core is a report of my recent bout of mental and digital housekeeping, but there’s also a reflective side [what It All Means] that has been more and more to the fore in the last 5 years: self explaining self to self by examining the Process. I’d like to think there’s something shareable with the like-minded others out there, something beyond the warm and fuzzy what a good boy am I sense that one gets from conversations with the Mirror.

My Word of the Year of 2024 was Curate, and I’m sticking with it for 2025 as I glance back over 2024 to see what I have and haven’t accomplished as a curator. In 2022 and 2023 the WotY was Narrative (see also the 2022 iteration), primarily concerned with extracting and articulating the Stories that I inhabit. Making sense of the STUFF that surrounds me…

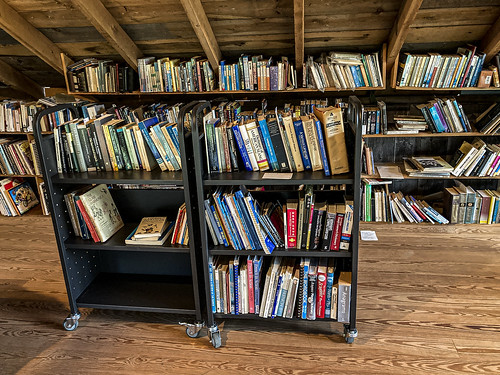

Curation is partly a matter of identifying and addressing messes, working at negentropy by organizing bits strewn about. Begin with the image of library shelves: where do items belong in relation to one another? But clearly it quickly goes beyond linear (2-D) arrangement, and the mental model I’ve used to invoke 3-D (and 4-D) relationships is macramé.

One hopes to construct an eloquent and artful structure for one’s Knowledge —partly to discover what it is that one Knows, and to work out how to map and navigate the construction. There’s something spider-like and web-tendy, though I’m less concerned with catching metaphorical flies than with being able to explore amongst what I’ve collected. Because I am and have always been a collector.

The habit/method/strategy of emailing links to myself (and of course to like-minded others) has been with me for a long time, indeed back to my first uses of email in the early 1990s. HTML gave me the tools to Keep Found Things Found (KFTF) by constructing Web pages to trace my progress/process. Before blogs became a thing, I was making “log files” of my discoveries, and trying to inspire colleagues and students to do likewise. I was more successful for myself than as an inspiration to others. It’s all at oook.info, reaching back 30 years.

And here I’ll invoke Informing Others, and cite the image of the Energizer Bunny to describe how my enthusiasm was received, but temper that vision with a digression into Walt Kelly’s Bun Rabbit, and the broader subject of avatars.

The thing is, all of this Informing is digressive, forever hareing off [gratuitous lagomorph reference] after another promising bit of curiosity/interest. Rabbit Hole does seem an apposite metaphor.

So my most outstanding mess/problem was the overstuffed email inbox of unread sent-to-self links, more than 1000. My Do Right page assembles my progress, much of it in the last two months. And what did I discover in assembling these chronological summary pages? The tracks of my curiosity and kaleidoscoping interests, laid out so they can be explored more easily: a nascent Index of my wanderings. Without such a catalog, it all becomes kind of a blur; but once the task is done, it’s practical to analyze the flow to discover and thus map my expanding and branching Interests. With every thing that crosses my path, there’s the question: how does it fit with and/or extend what I already know? And who of my Information clients would wish to know?

I have a lot of sensors/feelers deployed in Infospace, via print materials (NYRB, LRB, Literary Review, etc), digital subscriptions (paid and otherwise), RSS feeds, and sites I visit regularly (viz. YouTube)

The problem of curating the incoming flood of YouTube videos is vexing, and my interim solution of links displayed on HTML pages isn’t very satisfactory. The chaos could be reduced by sorting according to … well, what? And what’s a sensible workflow to get from lists to appropriate subcategories? Still thinking about THAT riddle.