March 2025 links begun, and March 2025 YouTube videos too.

This mode of curation/gatheration seems to be working pretty well.

Category Archives: video

keeping track

I’ve bundled the February YouTube finds into a suite of 7 connected pages (so that they load more reliably and quickly), and just barely started a location for extracts from my yellow pads since 2018. The page of February links is unwieldy, but I haven’t decided what to do about that.

The tag cloud for my LibraryThing is updated and still under revision, but provides the beginnings of subject access to books on my library shelves.

And the Lexicon Project burgeons.

more KFTF

After a week away, a lot has accumulated in the form of links sent to myself, and collecting them here seems …efficient as a means to be able to find them again:

I also happened upon a piece I wrote in 1993, in the early years (30+ ago) at Washington & Lee:

Timelapse of Kate’s House Set

(again, Tenants Harbor, not Owl’s Head)

Kate’s house is SET!

Earnest and Bogus’s Big Adventure part 3

“Hm.” I remember thinking. “Need to provide entrée to the collectors who found, preserved, annotated, packaged, released, and loved this music. And to the venues and mass media outlets that brought it to broader publics…” and the more I look into the background, the more stuff I find to explore and include, so more searches get done, more stuff gets ordered and read and heard. Case in point:

Just flew in through the transom: The Harry Smith B-Sides (“the flip side of 78-rpm records that Harry Smith included on the Anthology of American Folk Music”).

Who needs this? Certainly the music-obsessed, those who have grown up with the Anthology (1952, reissued on CDs 2007… and download !!liner notes!!) and its sequelæ Anthology Of American Folk Music Volume 4 (Revenant Records 2000) and The Harry Smith Project: The Anthology Of American Folk Music Revisited (2006), and the lucky few who followed gadaya’s labor of love MY OLD WEIRD AMERICA An exploration of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music blog when it was alive for downloads of the Variations.

The B-Sides are fully as revelatory as the 84 cuts on the original Anthology:

a mirror image of the Anthology… a way to hear the complete statement of each 78RPM disc… as they were originally released in the 1920s and 1930s…

Most people interested by the Smith Anthology will agree that it stands as an esoteric beacon outside the whole dysfunctional culture system. Just like when it was first issued in 1952, you still won’t hear the music of the Smith Anthology on the radio, on TV or on the front pages of the internet…

By releasing his Anthology to the audience of Folkways Records, Harry Smith dropped an extraordinary rural working class culture bomb on a New York City world of artists, bohemians, radicals, and city musicians… (Eli Smith, B-Sides liner notes)

A New York Times story on the B-Sides: How to Handle the Hate in America’s Musical Heritage

The 1927 Bristol recording sessions (the Big Bang of country music) captured 76 songs, recorded by 19 performers or performing groups, including the Carter Family.

The saga of recording Black musicians in the 1920s was somewhat more haphazard. There was a booking agency for the Black vaudeville circuit, the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA, referred to by Ma Rainey as ‘Tough On Black Asses’) that dealt with jazz, comedians, dancers and (mostly female) blues acts (Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith). Country blues artists were mostly too small-time and local for TOBA, and were recorded in studios outside the South (e.g., “Paramount Records, based in Port Washington, Wisconsin. The company was a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company, who also made phonographs…”) but the musicians were recruited by

“field scouts” [used] to seek out new talent, though this is a somewhat grand name for men the likes of HC Speir, who ran stores in the South and simply kept an eye out for local musicians. Through Speir they recorded Tommy Johnson and, most importantly, Charley Patton. It was Patton that took Son House, Willie Brown and Louise Johnson to Paramount’s new studios in Grafton WI in 1930.

Several record companies had catalogs of “Race Records” made for a specifically Black rural public, and it is these disks that were rescued by record collectors in the 1960s.

Thinking about mass media and Nacirema musics, one of the constants for most of the last century has been Grand Ole Opry, which was first broadcast from Nashville in 1925 and came to blanket the rural South with versions of aural and, eventually with TV, visual imagery of regional culture. Separating the authentic and vital from the stereotyped and bogus is challenging, and just how accurate and inclusive the picture was/is/can be argued endlessly. The intrusions of commercial elements are everywhere, and might as well be acknowledged while we hunt for whatever purity they blanket. Resort complexes like Opryland USA and Dollywood and Branson MO and Graceland have drawn crowds seeking ‘authentic’ experiences, and have provided income for entertainers.

The cultural complexity of the Showcase experience is exemplified by Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973), who was a lawyer, performer, researcher, field collector, impresario, and tyrant for the cause of what he spoke of as “mountain music.” His Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville NC (first in 1928) was the paradigm for many other folk festivals.

Lunsford himself despised the commercialism and cultural nonsense he saw in Asheville’s Rhododendron Festival, and opposed the stereotyping of mountain folk as backward and ignorant. Still, as a performer he could produce material as bogus as Good Old Mountain Dew

A documentary on Lunsford, This Appalachian Music Man Lived A Beautiful Life, in which Alan Lomax shows up:

and David Hoffman’s Bluegrass Roots 1965 was filmed in a mountain tour conducted by Lunsford:

John (1867-1948) and Alan (1915-2002) Lomax are giants in the history of discovering and recording Nacirema music in the field. A site from the Musical Geography Project offers maps of Lomax travels. John Szwed’s biography of Alan Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World is excellent, and Duchazeau’s Lomax: Collectors of Folk Songs is a charming graphic-novel portrayal of a 1933 Lomax collecting foray into the South. Among the interesting videos on Alan Lomax:

Cultural Equity has a vast collection of Alan Lomax field materials

Wikipedia lists more than 50 American folk song collectors, and American Folklife Center has a page of women collectors, including Frances Densmore (1867-1957), Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle (1891-1978).

Mike Seeger’s fieldwork in Appalachia brought Dock Boggs (1898-1971) to modern audiences and covered a wide range of southern styles of music and dance. Just Around The Bend: Survival & Revival in Southern Banjo Sounds was his last documentary film, and there are several documentary CDs and DVDs: Close to Home: Old Time Music from Mike Seeger’s Collection, 1952-1967, Mike Seeger Early Southern Guitar Styles, Early Southern Guitar Sounds, Southern Banjo Styles #1 Clawhammer Varieties & more, Southern Banjo Styles #2-Early 2- and 3-Finger Picking, Southern Banjo Sounds, besides his work with the New Lost City Ramblers, his sister Peggy, and various other musicians.

Art Rosenbaum’s Art of Field Recording (1 and 2) (available via Dust to Digital) offers a wealth of field recordings made 1959-2010.

Record collectors inhabit a separate documentary world, well described in Amanda Petrusich’s Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records.

…an intense, competitive, and insular subculture with its own rules and economics—an oddball fraternity of men (and they are almost always men) obsessed with an outmoded technology and the aural rewards it could offer them. Because 78s are remarkably fragile and were sometimes produced in very limited quantities, they’re a finite resource, and the amount of time and effort required to find the coveted ones is astonishing. The maniacal pursuit of rare shellac seemed like an epic treasure hunt, a quest story—an elaburate, multipronged search for a prize that may or may not even exist. (pg. 4)

Among collectors of 78s, Joe Bussard stands out as a National Treasure. A Fretboard Journal profile introduces his rather unique personality:

Joe Bussard has an interesting theory: Musical forms seem to lose their value when the electric bass is introduced. “That goddamn electric bass ruined everything!” he shouts. “I went to Trashville—I mean Nashville—in ’57 to see the Opry, and I asked for my money back, I’ll tell you that right now. They didn’t have shit I wanted to hear. Garbage! When rock come in, I didn’t have any interest in anything that damn dumb! Elvis and all that bullshit! I already knew better than to fall for that, buncha goddam shit for retarded 4-year-old kids!”

but its essence is best appreciated in videos:

Joe has been very open-handed with his collection, making tapes for people and contributing to a vast array of compilations. There’s a video Desperate Man Blues: Discovering the Roots of American Music that I’d love to get my hands on. Looks like I had it in 2007 from Netflix, and I’ve requested it again.

Besides his Fonotone Records recording business which ran for a decade or so and lately produced a remarkable compilation

Massive 5CD set of American Primitive music unearthed for the first time (in various styles: Jug Band, Country, Old Time, Blues and Bluegrass), recorded and documented by Joe Bussard’s 78-RPM Fonotone label, 1956-1969 — not one track previously on CD before. Incredible package featuring 131 tracks over 5 discs, 160-page perfect-bound book, 17 full-color postcards, 3 record label reproductions in souvenir folder and a nickel-plated Fonotone Records bottle opener(!) — all packaged in a deluxe cigar box.

Joe Bussard recorded the young John Fahey in 1959-1960.

John Fahey deserves mention under Collectors for his part in the rediscovery of Bukka White and Skip James (both of whom had made mighty 78s in the 1920s), described in detail in Dance of Death: The Life of John Fahey, American Guitarist, and for the research he did on Charley Patton, and other Revenant Records collections American Primitive, Vol. 1: Raw Pre-War Gospel (1926-36) and American Primitive Vol . 2 – Pre-War Revenants (1897 – 1939).

Fahey’s life was a trainwreck, with occasional bright interludes, and is perhaps best discussed under Guitar Heroes.

The fraternity of collectors is nicely documented via Mainspring Press (“Information and Resources for Historic-Sound Enthusiasts”, including Discographies). Their blogroll provides links to Excavated Shellac (mostly concerned with non-US sources) and Sound of the Hound (“dedicated to the story of how recording came into being and how it conquered the world”). See also Amanda Petrusich on John Heneghan and The Great 78 Project at the Internet Archive.

Some collectors have specialized in “ethnic” 78s (a whole other subset of my musical world), including Dick Spottswood (who grew up near John Fahey) and Ian Nagoski (of Canary Records and Fonotopia) and Karl Signell. See also 78rpm Collector’s Community (“a social network for collectors of 78rpms recordings, phonographs, memorabilia, recording machines and the history of the 78 rpm recording era”)

Experiments with recording at 78 RPM include American Epic (and accompanying CD and book).

Earnest and Bogus’s Grand Adventure, part 2

(and surfacing topics to be expanded anon)

(but barely scratching the surface)

Here’s a list I made for myself of issues to explore:

- the “real folk” and the Tradition

- authenticity and interpretation

- versions and versioning

- collectors, researchers, profit seekers

- commercialization

- the True Vine

- appropriation

- the place of folklore scholarship

To begin with the last of those, I reopened a file folder of notes and documents from summer 1991, when I spent a couple of months looking into issues of librarianship and access in the world of academic Folklore studies. I also hunted up some books on Folklore that I’d acquired then (Dundes 1965, Dorson 1972, Brunvand 1978), but found them unappealing and pretty much irrelevant to my Nacirema musics Finding Aid, since academic Folklore seems uninterested in the commercial world that produced the shellac and vinyl and digital documents, and ditto in the earnest efforts of non-“folk” musicians to study and then extend the works of early 20th century progenitors. Far more useful than the academic texts are liner notes from albums and books by non-academic enthusiasts who are free of the carapace of academic disciplines. There’s still plenty of contentious territory—John Fahey’s How Bluegrass Music Destroyed My Life represents that well.

It’s worthwhile to look into the work of 19th and early 20th century ballad scholars (Francis James Child and George Lyman Kittredge, Harvard professors of Rhetoric and English who sparked interest in texts and comparison), the songcatcher collectors (Cecil Sharp, Maud Karpeles, a few others), and the extra-academic road warriors (the Lomaxes père et fils most notably) who went out to record the “folk” in the 1930s. These were especially effective creators and anaysts of the body of work that the folk revivalists of the 1960s drew upon. Alan Lomax (as a fieldworker) and Moe Asch (as promulgator) laid the foundations; Harry Smith, Ralph Rinzler and Mike Seeger understood the potential locked away in all those 78s from the 1920s and 1930s. And a ragged band of collectors went out searching for revenant 78s and so eventually provided the feedstock for reissue compilations. In some cases they also found the still-living musicians who had made the records. Folk festivals and college tours acted as fuel for a boom in interest that also spawned coffee houses and record deals for performers.

A few LPs ignited the smouldering tinder. Joan Baez’s first album (1960) was one such for many people, and “Silver Dagger” pinioned (maybe even created) a whole generation of folkies:

The Wikipedia article on the song puts the Baez version into context: one of many variants, not a Child Ballad (though several on the Baez album were), and covering the same territory of love-and-death that runs wide and deep in folk and popular musics. Deja Morgana’s summary is helpful, and even Thomas Merton was bewitched:

“All the love and all the death in me are at the moment wound up in Joan Baez’s ‘Silver Dagger,'” the man wrote to his lady love in 1966. “I can’t get it out of my head, day or night. I am obsessed with it. My whole being is saturated with it. The song is myself—and yourself for me, in a way.”

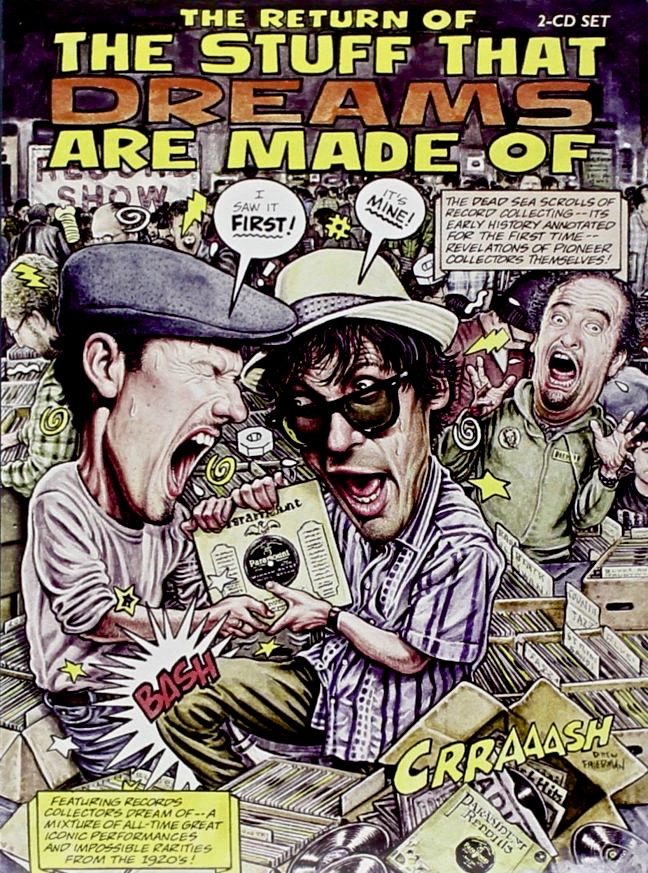

Fascination with particular instruments is another vein in the deep mine of the folk revival. The distinctive sound of the plucked string (guitar, banjo, dulcimer, mandolin…) and the powerful magnet of virtuosity (how does he/she DO that?) fueled the (largely unexamined) mania for playing that afflicts a small proportion of those who are attracted to this music. This minority is the feedstock of woodshedders and performers and instrument collectors whose obsessions underpin the vast edifice of tunes and drive the evolution of the various genres of popular music. And evolution there is, and has always been. For such folks, periodicals like Fretboard Journal and the now-defunct Mandolin World News (1978-1985) are tailor-made, and bits of lore like Ry Cooder’s instruments and David Lindley’s instruments are eye candy, the Stuff of which Dreams are made.

The life stories of the personalities in these musical worlds are a perennial fascination: how did they first become musicians, who and what influenced their development, with whom have they played, what demons have they wrestled with… A few examples:

- Can’t You Hear Me Callin’: The Life of Bill Monroe, Father of Bluegrass

- The Mayor of MacDougal Street: A Memoir (Dave Van Ronk)

- Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story

- Been So Long: My Life and Music (Jorma Kaukonen)

- Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius

- Music from the True Vine: Mike Seeger’s Life & Musical Journey

and the interwebs are replete with interviews with and profiles of heroes: David Grisman: Acousticity And Other Dawg Dreams and Bela Fleck are two nice examples.

Turning a passion for music into a viable career is perilous, and it’s has been true for the last century at least that life “on the road” is the lot of most who try to make a living from music: festivals, concerts in a string of cities, occasional tv and radio appearances, maybe recordings. Many also eke a living from session and sideperson work with recording studios. Austin City Limits, the NPR Tiny Desk miniconcerts, and personal YouTube channels are relatively new venues for performers, designed to reach wide audiences, but most “folk” musicians live pretty much hand-to-mouth. Needed here, and probably the subject of the next post in the series, is consideration of mass media (radio, TV, YouTube…), festivals and concert venues, and the infrastructure of the recording industry (A&R, studios, record labels)—stuff I know is important in the overall story, and missing pieces in the context of the Nacirema musics in my collections. Only a few of these are part of my experience, but they’re things I need to learn about as mise-en-scène for the music I experience by ear.

Meanwhile, a few videos of some of my own musical heroes:

Norman Blake:

John Hartford (1937-2001)

Master of Ceremonies for the inaugural Ryman Auditorium performance of “Down From The Mountain”, an absolute must-see concert film.

Lebowskiana

This post may be tl;dr for some, but seems a necessary attempt at summary for me, and may be useful to other Convivium participants who might still be puzzling over things I invoked in last week’s bout

Yesterday Betsy asked what did I mean in citing “the Dude abides” in answer to her “no-self” citation of the Diamond Sutra, in the continuing discussion over personal response to the question of how we severally think about The Big Picture. I fumbled an explanation along the lines of Here I am, I’m doing what I do and further cited the Kurt Vonnegut tagline “and so it goes…”. Unsatisfactory, and ever since I’ve been thinking about how to explain more fully.

Here’s how one explicator of the Vonnegut quote puts it: “the inexorable universe doesn’t care one whit about our lives and it’s up to us to make of them what we will… it’s just me and my mind making things up.”

(“And so it goes” appears more than 100 times in Slaughterhouse 5, each a reflection on a death observed.)

My impulse to make light of serious things, to resort to the cynical and sardonic, to voice extreme sentiments that exaggerate what I actually believe … is sometimes baffling and even hurtful to others, or at least confusing. This wants explication.

Perhaps I should be asking: whom do I really Respect and why and how? Kurt Vonnegut would be pretty high on the list, and his Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons would be a primary text, hot stuff from its very first pages and a distillation of his thoughts on self and writings. If you’re not already familiar with the titular terminology, Vonnegut explains:

A wampeter is an object around which the lives of many otherwise unrelated people may revolve. The Holy Grail would be a case in point. Foma are harmless untruths, intended to comfort simple souls. An example: “Prosperity is just around the corner.” A granfalloon is a proud and meaningless association of human beings… [a college class, viz. Harvard 1965, would exemplify]

I have a long history of wee-hours pondering, in which I’m awake at 3 AM, thinking in words and phrases that evaporate like dreams unless I arise and write them down. This morning’s iteration was spawned by the “the Dude abides” showstopper from this week’s Convivium—in which I said something that the others found Delphic, impenetrable, completely off the wall… being, as they were, unfamiliar with the allusion to The Big Lebowski, and thus completely at a loss to know what I meant. The 3 AM phrase that got me up and writing was a characterization of my state of mind in alluding to “the Dude abides” as my take on the Big Picture and how to characterize it:

and I soon added ‘transgressive’ to those three.

So now, a few hours later, I’m trying to unpack all of that, explain it to myself and perhaps to others, and make sense of the incident… which will take us pretty far afield, for who knows what constructive purpose.

The Wednesday evening Convivium sessions (these days conducted over Zoom) are, so it seems to me, opportunities for 4-5-6 of us to explore how we see, interrogate, and experience the world… which may not be what my interlocutors think/perceive/wish. Generally they seem to me to be of the Spirit and the spiritual to a greater degree than I think I am. I have a pretty agnostic view of Spirit and spiritual for myself, but am thoroughly willing (I hope, or maybe wish) to cut others slack in their own conceptions and practices.

As I’ve said rather tiresomely, I take refuge in projects and explorations, defined by a lifetime of exploring edges and interstices, of finding the joke and exploring the significance of the preposterous. There: ‘exploring’ 3 times in one sentence. It’s what I do. Why, and whither, and whence I only barely understand. Occasionally I encounter others of similar proclivities, and some of those have been lifelong friends.

For many years (at least since the late 1960s) I’ve considered that I was engaged in Nacirema and Naidanac studies, which specialty is ultimately inspired by Horace Miner’s Body Ritual among the Nacirema (American Anthropologist 1956).

…According to Nacirema mythology, their nation was originated by a culture hero, Notgnihsaw, who is otherwise known for two great feats of strength – the throwing of a piece of wampum across the river Pa-To-Mac and the chopping down of a cherry tree in which the Spirit of Truth resided…

The documents of this backwater of anthropology include many films that could only be American (there are films that could only be English, or Swedish, or French, etc.—that have contents and characters that simply are not thinkable as American). Translation across cultural boundaries is perilous, as exemplified by [perhaps] well-meaning efforts to translate dialog. Yesterday I watched The Big Lebowski with French subtitles, which obscured about 90% of the humor as it would be appreciated by a native speaker. “Dude” is glossed as “Mec”, for example…

So the immediate problem is to explicate what I see in The Big Lebowski, why I regard it as “one of the best…”, why I’m gobsmacked that everybody doesn’t know it for the cultural icon I believe it to be, and so eventually to arrive at why I cited “the Dude abides” as my own take on elements of The Big Picture. I do have to recognize that some of this is, as we say, non-transitive—it may not be explicable/understandable to others, and my take may reduce in their perception to another example of oook’s frivolous, flippant, profane stance toward the sublime and numinous, toward what really matters. So it goes, to invoke Vonnegut again.

I think a substantial element in my Umwelt (“self-centered world”—a coinage of Jakob von Uexcüll [1909]: “the small subset of the world that an animal is able to detect“) arose from/in California 1956-1961. Just how might be discoverable via introspection, but the details are for another time. The notion that fictional characters in literature, in films, in songs, in visual imagery can encode and express verities is surely at the core of what California taught me in those years, and is obviously the bedrock of the movie industry. The Sam Elliott character who NARRATES The Big Lebowski is obviously a necessary/essential fabrication; and the Dude may be, as Sam Elliott says, “a man for his time and place”… We enter a world of total fantasy, populated by preposterous characters who nonetheless REFLECT realities we recognize as possible, plausible. Walter Sobchak is a Type; Maudie and the Big Lebowski himself and the other goofballs who populate the film are not without some relation to reality. Or Reality. Julianne Moore [Maude Lebowski] puts it thus:

I feel like we all kind of know people like the Dude, or have known people like the Dude in our lives, this whole idea that the Dude abides. He’s always there, always doing his thing. There is something about him that is straightforward and honest, and he is who he is. And he’s hung onto that, you know? He hasn’t been deterred by time changing.

(I’m a Lebowski, You’re a Lebowski: Life, The Big Lebowski, and what have you, pg 40)

It’s the preposterous that makes the film memorable, that captures our attention in every scene. NB other books: The Abide Guide: Living Like Lebowski, The Dude De Ching: New Annotated Edition, and The Tao of the Dude: Awesome Insights of Deep Dudes from Lao Tzu to Lebowski, all by by Oliver Benjamin…

But would I read the film in that way if I hadn’t been transported from New England sensibilities in 1956, at age 13, and immersed in Southern California for the next 5 years? And if I hadn’t spent another formative 5 years in the Bay Area, 1967-1972?

8 x 10

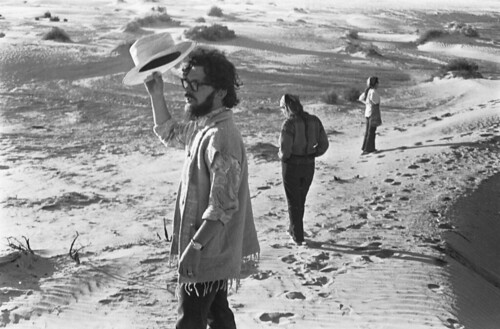

In the Spring of 1969 we spent most of a week in Death Valley with Kent and Shel and Jaca and her brother Kenny and his dog Pie. For us it was primarily a photographic expedition, and I have lots of as-yet-unscanned negatives from the adventure. Here are a few that have transitioned to digital:

At that point we had a half share in an 8 x 10 camera, with which I wrestled off and on (these photos by Broot, of course):

What brought that to mind today was this marvelous little YouTube drama, the hilarity of which may not be fully obvious to those not deep-dyed in the mystical side of photography. It’s all there: the Equipment Fallacy that especially afflicts male photographers, the Resolution bugaboo, the sweaty palms of setting up and taking the shot, the agony of waiting for a result, the pretense… and zoodles.

Rabbit Hole du jour

You just never know what the day will bring, and how thing will lead to thing.

I started with a chapter from Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler, the second part of the first one, which finds the reader in a provincial town railroad station:

The novel begins in a railway station, a locomotive huffs, steam from a piston covers the opening of the chapter, a cloud of smoke hides part of the first paragraph. In the odor of the station there is a passing whiff of station café odor. There is someone looking through the befogged glass, he opens the glass door of the bar, everything is misty, inside, too, as if seen by nearsighted eyes, or eyes irritated by coal dust. The pages of the book are clouded like the windows of an old train, the cloud of smoke rests on the sentences…

Not in Kansas anymore, hein?

The word that springs to mind is “immersive” but whether anybody else has ever been so sprung upon I know not. At the end of Calvino chapter 1 I begin to read chapter 2:

You have now read about thirty pages and you’re becoming caught up in the story. At a certain point you remark: “This sentence somehow seems familiar. In fact, this whole passage reads like something I’ve read before.” Of course: there are themes that recur, the text is interwoven with these reprises, which serve to express the fluctuation of time. You are the sort of reader who is sensitive to such refinements; you are quick to catch the author’s intentions and nothing escapes you….

Hm. And so I put down Calvino and picked up where I left off yesterday in Becker’s Many Subtle Channels: In Praise of Potential Literature (Calvino having been a Oulipian, this seemed perfectly sensible) and the feel of the reading seems the same, some amalgam of fictional narrative and factual discourse where it’s perhaps difficult or possibly pointless to say what is real and what imaginary…

And then a look at the RSS feed’s latest brought me this:

And I think: A new genre? Meld of sound and metacommentary, which turns out to have been “inspired” by William Eggleston, and in some sense the whole video is about William Eggleston.

You know what? Just google him now. Pause this video.

Now, I’ve never gotten William Eggleston as a photographer, and the why of that is surely worth exploring. I accept that he’s widely regarded as one of the modern masters, and I know that John Sarkowski, whom I revere, recognized him with an early solo show at MoMA in 1976 (the first of color photography): William Eggleston’s Guide is Szarkowski’s catalog for the show, and see also a pdf of Szarkowski’s Introduction. Here’s a section of the Amazon blurb for the book:

The book and show unabashedly forced the art world to deal with color photography, a medium scarcely taken seriously at the time, and with the vernacular content of a body of photographs that could have been but definitely weren’t some average American’s Instamatic pictures from the family album. These photographs heralded a new mastery of the use of color as an integral element of photographic composition.

My own photographic aesthetic is deeply dipped in the world of black-and-white photography, mostly before 1976, though I’ve taken to color myself ever since my transition to digital imaging more than 10 years ago. Eggleston’s color and composition just rub me the wrong way, and generally my reaction to his images has been “so what?”, but a couple of years ago I saw a selection at full size at Pier 24 in San Francisco, and began to realize that my judgements have been ill-placed. So I continue to try to reeducate myself away from long-running prejudices. But I’m still leery of Eggleston.

So back to the video, and its “new genre” possibilities, and how all of that might fit with Calvino and with OuPhoPo (the Workshop in Experimental Photography). The text of the video references a New York Times profile of Eggleston, in which he is revealed to be an over-the-top alcoholic.

…WE LEAVE THE OFFICES of the Eggleston Trust and go to his apartment. The first thing one sees upon entering is a bright red plastic sign with a yellow border, printed with capitalized white sans-serif text. It warns, “THE OCCUPANT OF THIS APARTMENT WAS RECENTLY HOSPITALIZED FOR COMPLICATIONS DUE TO ALCOHOL. HE IS ON A MEDICALLY PRESCRIBED DAILY PORTION OF ALCOHOL. IF YOU BRING ADDITIONAL ALCOHOL INTO THIS APARTMENT YOU ARE PLACING HIM IN MORTAL DANGER. YOUR ENTRY AND EXIT INTO THIS APARTMENT IS BEING RECORDED. WE WILL PROSECUTE SHOULD THIS NOTICE BE IGNORED. THE EGGLESTON FAMILY.” It is a devastating thing to see. Heartbreaking. I was also an alcoholic for decades, the kind who had shakes and saw spiders. I’m not even through the hallway and my mind is racing from “I want that sign” to “What kind of doctor prescribes alcohol for an alcoholic? Where was he when I was drinking?”

The text of the song in the video:

What if the thing that helps you live

Is also the thing that will get you killed

It’s the damndest thing

I don’t think I’d ever heard of Beauty Pill, but here are two more remarkable videos:

Africana Barista

and

Dog With Rabbit in Mouth Unharmed

which make me realize that I need to make more room in my musical universe.

And that was all before 10 AM.