Joerndts

(this is just a beginning of a continuing Saga)

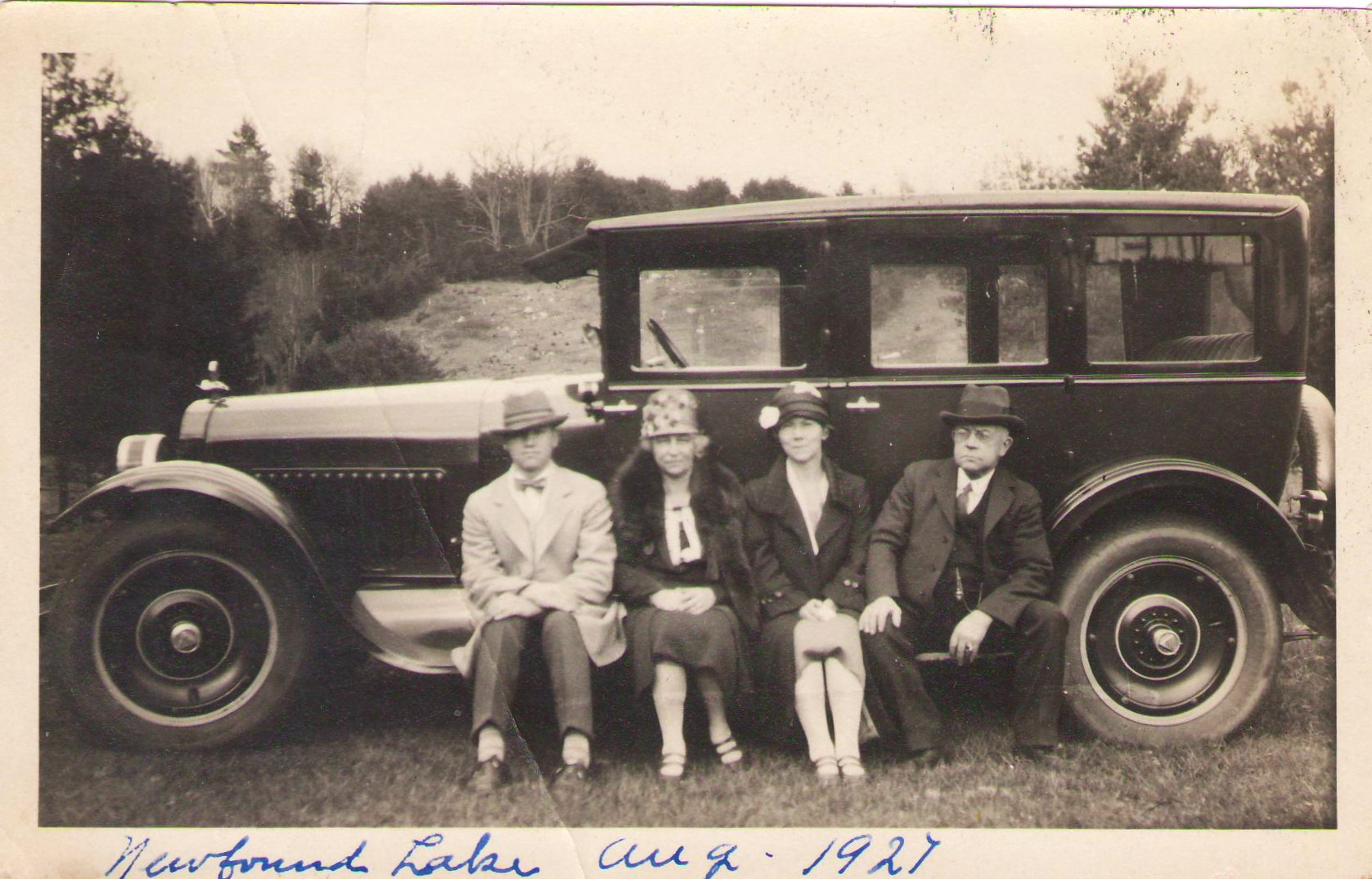

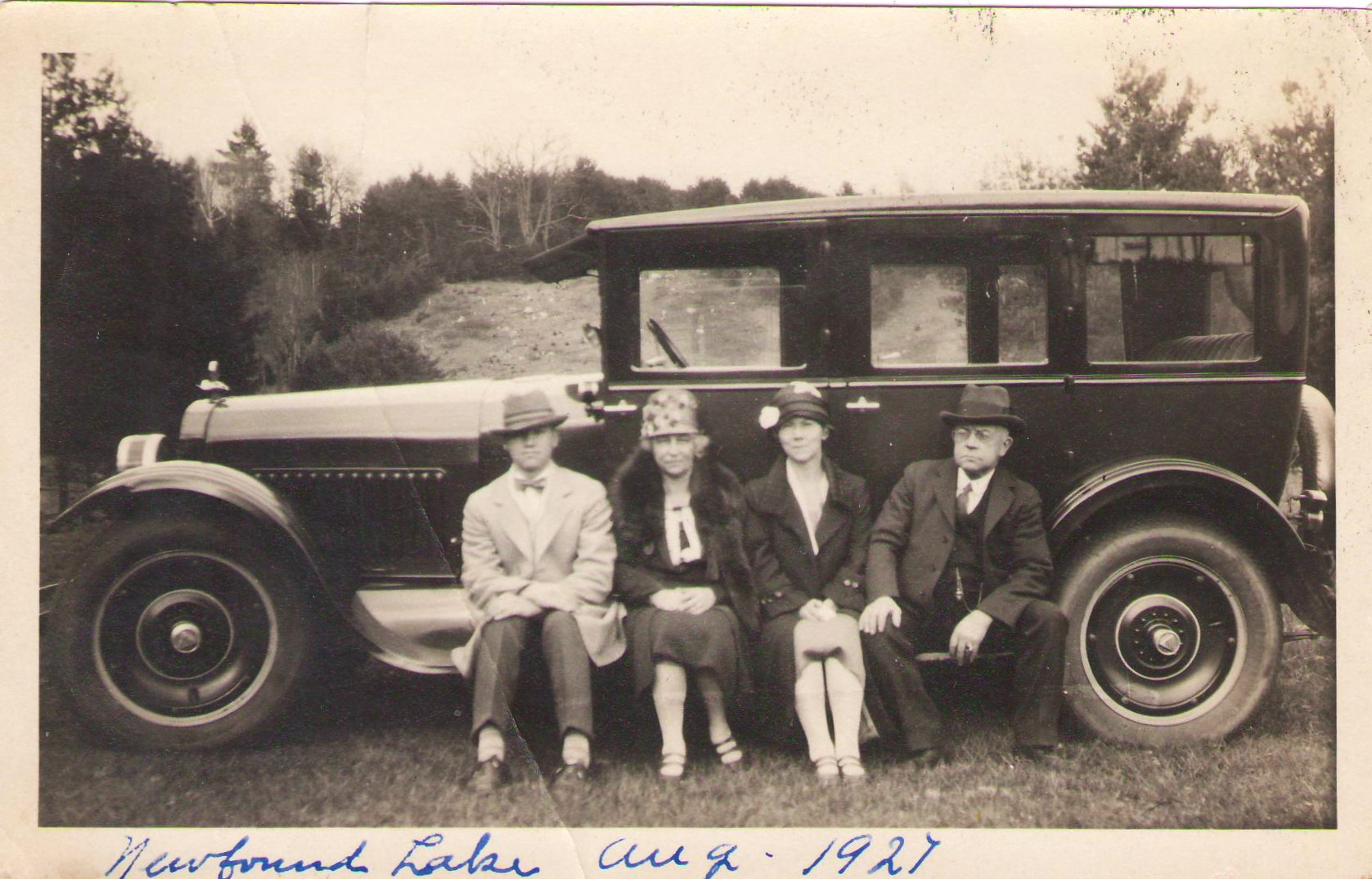

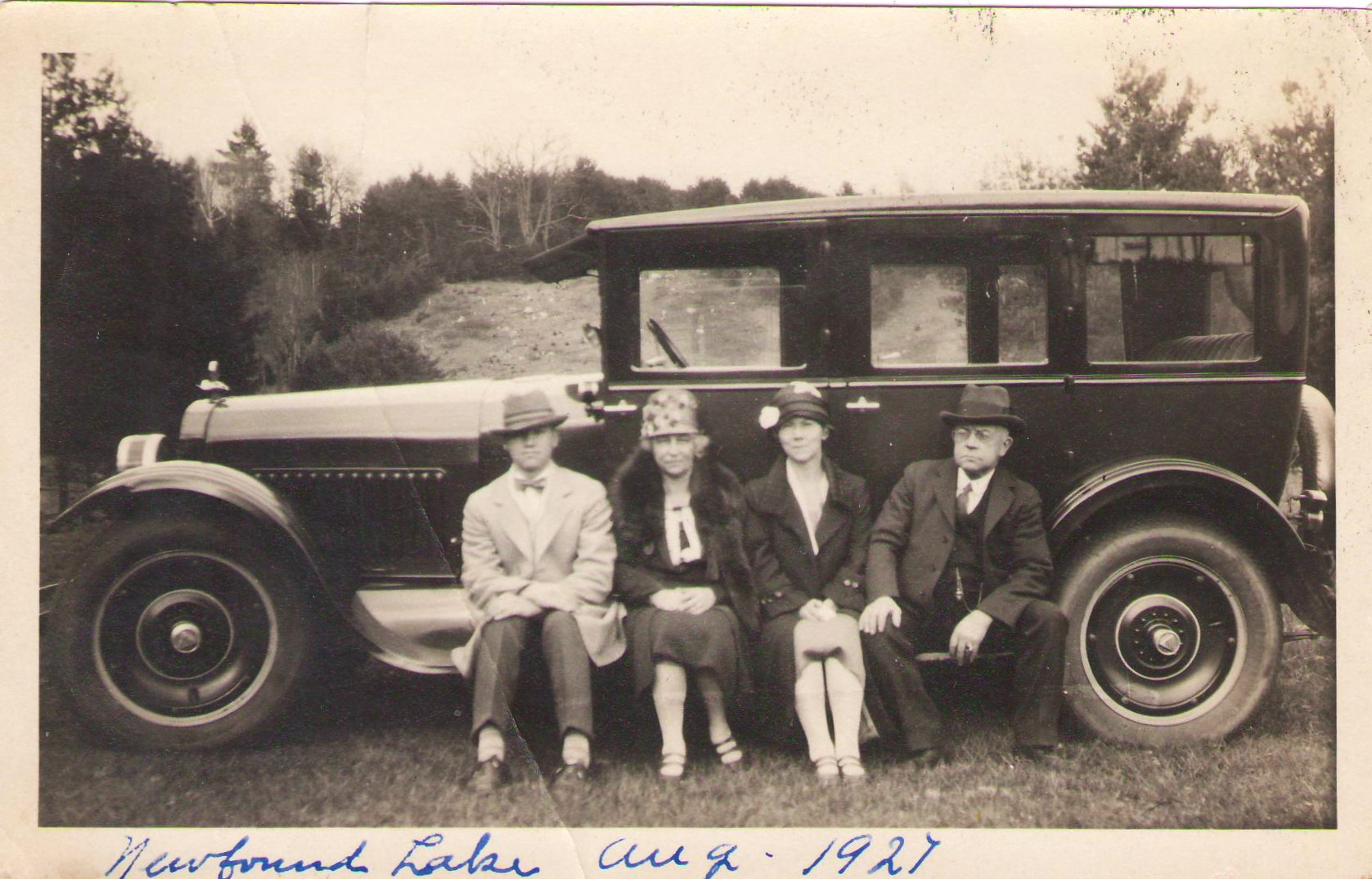

Photographs from the past ENCODE messages that may/can resonate across time. In fact, that’s how they work, in a sort of temporal accordion (folded up and hidden until the bellows are tugged open, then producing stored/implied/immanent/nascent SOUND). Above is a photo of my maternal grandparents, whom I have never seen pictures of. It arrived in my life this week (indirectly, from a first cousin once removed whom I’ve never met) and I’ve been working on investigating and unpacking the story it tells, and the Story it is a fragment of evidence within.

I have spent many many happy hours in the company of the Abandoned Ancestors of others, and also in my own trove of family photographs, passed down into my curatorship from earlier generations. The pleasure/game/discipline of reading images, of excavating stories, imputing personality and other characteristics, and connecting up the (sometimes fanciful) dots … is bottomless and basically harmless to anybody now living, or so I tell myself.

The people are: Carl Kikkebusch, Mary Joerndt, Harriet Joerndt Kikkebusch, and William Henry Joerndt.

Harriet is my mother’s elder sister (by 9 years). I “know” bits about each of these four people, though the knowledge is somewhat suspect, or at least heavily inflected, by (1) what I remember of (2) what my mother (who died in 1972) told me about her family of origin, (3) what my sister Alice (who died in 2010) told me, and (4) what I’ve deduced for myself from such family papers as I preside over… and in the last week, (5) a lively correspondence with my sister’s oldest nephew (is he my nephew-in-law? There’s no Nacirema kinship term for the relationship).

What can we read from the photo? How would backstory enlarge our reading? Where does this photo fit in the catalog of genres of vernacular photographs and snapshots? [people and cars…]

Walt Whitman would agree that these images contain multitudes —well, any image does, and the viewer’s opportunity is to explore those multitudes, all the better to deepen one’s appreciation for humanity and the vast complexities and complications of people’s lives and relationships.

So how is it that this is the only photograph I’ve ever seen of my mother’s parents, and that that seeing was just a week ago? Short answer: as I understand it, my mother was estranged from her parents from about age 14. I believe this to be rooted in a Joerndt family tragedy in 1908, resulting in the death of 3-year-old Marshall …and the subsequent divorce of the parents, evidently over the mother’s resort to various ‘spiritualisms’ in order to reach Marshall (that may be apocryphal, as may be the possible institutionalization of the mother). There’s much more to this drama, but there’s nobody left who knows.

The effect upon my mother between ages 9 and 14 was enormous and profound: her family “broken” (the term of choice in that era) around her just as she was emerging into personhood. At 14 she was sent to school at Urbana OH. Here’s how she described her state of mind:

I came here here hungry for affection, disturbed about the way I had seen people injure each other, and about as confused as a young girl can get…

Being sent to Urbana was utterly and completely the rescue that she needed:

Urbana University Schools, Urbana Ohio

Sixtieth year opens Sept 21, 1910

All grades from Kindergarten to second year of college

Especial attention given in regular classes

to instruction in The Word and the Doctrines of the New Church

Good, wholesome influences surrounding students

both in and out of school.

A few scholarships available

Paul H Seymour MS

Headmaster

So we find ourselves in a Swedenborgian world, in which both of my parents grew up (my father in the Boston Society) and lived their lives. Just how the Joerndts came to be in that world is a mystery, but the Humboldt Park Society of the Church of the New Jerusalem is the locus. Rob Lawson suggests

Carl and Henrietta Joerndt [William’s parents] would have been very knowledgable of the New Church German Society as early as the 1850s. The Pastor of this branch of the Chicago Swedenborgians, John Henry Ragatz, was from Switzerland and a contemporary in age with the Joerndts&mdsah;just a few years older than Carl. Ragatz started out as a minister of the Joerndt’s Lutheran Evangelical Church, of which the Joerndts remained members at least up to 1899. When Ragatz started the German New Church in 1854-55, the Joerndts may have had friends who left the Lutheran church to hang out with their Pastor Ragatz and his new-found adoption of Swedenborg’s spiritual offerings. It’s just a guess…

Aunt Harriet and Carl Kikkebusch were married in the Humboldt Park church in 1910, and at one point both my mother and her younger sister Eunice were sent to live with Harriet and Carl. Somebody in the Humboldt Park Society suggested and then managed my mother’s flight to Urbana, but I know none of the details.

Just to relieve the suspense, a few more bits of the story: after the divorce, William married again, one Augusta Knopf, who died in 1926. He then married (wait for it…) …Mary Joerndt in October 1926, in California… and both Harriet and Eunice were living in California in the early 1920s. The Mary Joerndt in the photograph

is physiognomically very similar to my mother when she was about that age.

While my mother was at Urbana, when she was perhaps 16, she had appendicitis and her father (by then a Christian Scientist) refused permission for the operation that would save her life. Alice Sturges, the Housemother, took responsibility and signed in loco parentis. Her father disowned her. Or so goes the story.

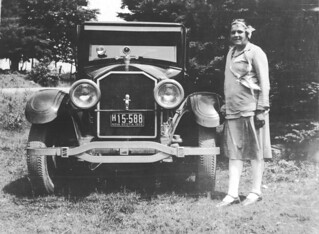

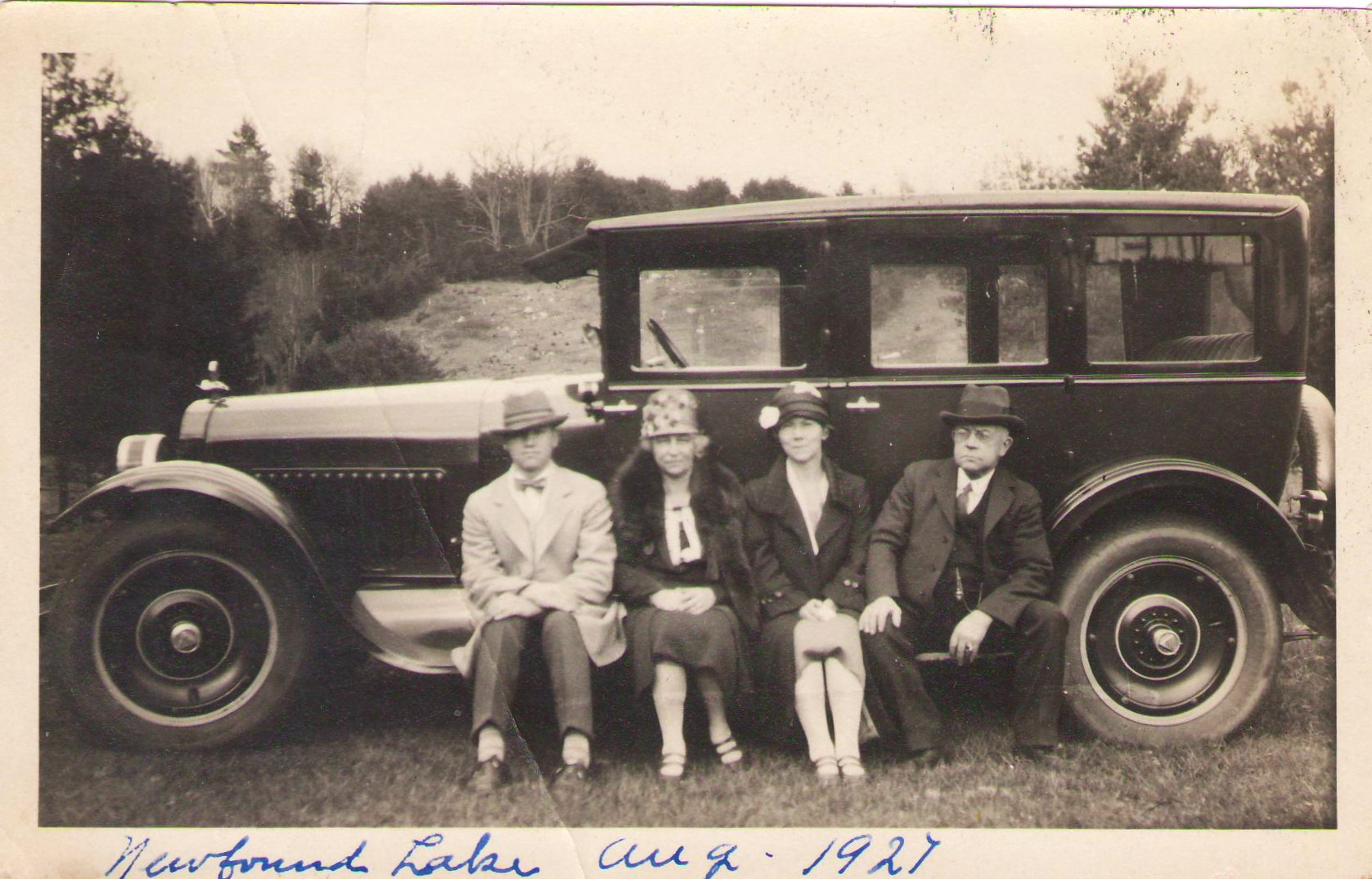

And here’s one of Mary Joerndt and Harriet in 1907: the year before Marshall’s death, when Harriet was 16:

This will probably be continued, so stay tuned.