The Fourfold Root of Stoic Virtue Steven Gambardella

(not sure what to include)

Between the Bauhaus and Bell Labs David Krakauer, Santa Fe Institute

The focus on thinking with all of one’s sense and sensibility was a dominant feature of the Bauhaus, where according to the art historian Magdalena Droste, “[t]hanks to their basic training on the hand loom, however, students were equally capable of running small, artistic crafts workshops” and “A profession was thus created within the textile industry which had rarely been found before — designer.”

Between the engineering design of Bell Labs and the artistic design

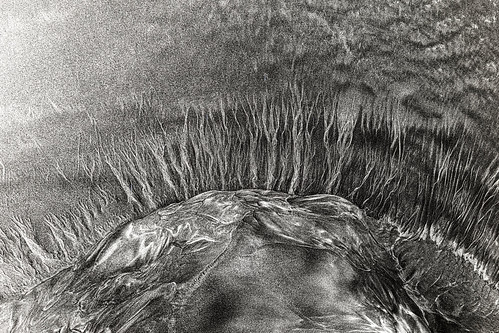

community of the Bauhaus, I like to position the Santa Fe Institute. Complex systems are that special part of the universe “designed” by natural selection and self-organizing dynamics or by human collectives: organisms, ecosystems, markets, computers, and cities. And all organizations dedicated to understanding design in this larger, distributed sense have no choice but to accommodate very different styles of thought.

…Our project is a radical one, which seeks to explore the frontiers of complex reality — the garden of machines, as it were — and emphasizes the precarious balance between individual iconoclasm, communitarian vision, and creative production.

Breathing Life into Bytes: The Enigma of Machine Consciousness Daniele Nanni

In the Western culture, thinkers like René Descartes championed the idea that our minds, distinct from our physical brains, hold our consciousness. His proclamation, “Cogito ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”), underscores that our self-awareness attests to our existence.

Following him, John Locke envisioned our minds as a tabula rasa (a blank canvas), gradually painted on by our life’s experiences. Contrastingly, David Hume saw consciousness as a mixtape of sorts, a collection of different experiences and perceptions. Immanuel Kant then threw in his two cents, suggesting our minds actively piece together our experiences into a cohesive narrative.

Fast forward a bit, and we find William James, a pioneer in psychology, proposing different “versions” of ourselves within our consciousness. And who can forget Sigmund Freud? With his iconic iceberg analogy, he illustrated our mind as largely hidden beneath the surface of our awareness.

As we mull over these Western theories, the East provides its own philosophical richness.

Ancient Indian Vedantic scriptures, such as the Upanishads, emphasize the concept of Atman or the inner self, and Brahman, the grand cosmic essence. They argue for a universal consciousness, where individual awareness is but a droplet in the vast ocean of existence.

Buddhism, with its profound insights from the Buddha, presents consciousness as ever-flowing. The doctrine of Anatta or “no-self” describes our conscious self not as a fixed entity but as an evolving stream of experiences.

Chinese philosophers weren’t far behind in their contributions.

Confucius rooted consciousness in relationships, emphasizing our interconnectedness. Then we have Daoism, with Laozi speaking of the Dao, suggesting that true consciousness aligns with the universe’s rhythm.

In juxtaposing these Western and Eastern thoughts, we discern a recurring theme: Consciousness is intricate, layered, and deeply connected to our experiences, surroundings, and perhaps even the cosmos.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Web3: The beginning of a digital renaissance? Jasvin Bhasin

(2010s)…a significant paradigm shift: the car was no longer seen as just a means of transport, but as a “computer on wheels” — a data machine equipped with lidar, radar and ultrasonic sensors. These sensors collected a wealth of data about the car’s environment. Enabled with deep learning and artificial neural networks the vehicles now made real-time decisions. Many car manufacturers also rolled out data intelligence platforms to implement next-best-action systems, that also used big data and predictive models. For example, to predict when a vehicle needs maintenance or provide recommendations for route changes based on traffic data. This capability to predict and plan actions based on data led to significant competitive advantage.

This era was also characterised by breathtaking visions where we imagined a future in which people owned electric vehicles that could drive themselves and recharge themselves. These vehicles were not only to be a means of transport, but also an integral part of our energy ecosystem. They could feed surplus energy into our homes and even offer the possibility to exchange this additionally generated energy via blockchain technologies in order to earn money with it…

…For a long time, the development of artificial intelligence was mainly seen as a sustaining and iterative innovation. But suddenly this perception has changed. Now, AI is seen as having a disruptive potential that is fundamentally changing our previous understanding of what qualifies as “work” and “creativity”. Another significant change was that during the era of the Internet of Things (IoT) and Industry 4.0, discussions focused mainly on the automation of factory workplaces. Now, however, the realisation begun to mature that knowledge workers could in fact be dispensable…

…Currently, a third of the world’s web traffic comes from just three companies: Google, Facebook and Twitter. At the same time, five companies — Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Meta — represent 50% of the total market capitalisation of the Nasdaq 100, a significant increase from a decade ago when their share was only 25%.

…Amara’s Law says: “We tend to overestimate the impact of a technology in the short term and underestimate the impact in the long term.”

Ambiguity Defines the Human Experience Douglas Rushkoff (from Team Human)

…we are mistaken to emulate the certainty of our computers. They are definitive because they have to be. Their job is to resolve questions, turn inputs into outputs, choose between one or zero. Even at extraordinary resolutions, the computer must decide if a pixel is here or there, if a color is this blue or that blue, if a note is this frequency or that one. There is no in-between state. No ambiguity is permitted.

But it’s precisely this ambiguity — and the ability to embrace it — that characterizes the collectively felt human experience. Does God exist? Do we have an innate purpose? Is love real? These are not simple yes-or-no questions. They’re yes-and-no ones: Mobius strips or Zen koans that can only be engaged from multiple perspectives and sensibilities. We have two brain hemispheres, after all. It takes both to create the multidimensional conceptual picture we think of as reality.

Besides, the brain doesn’t capture and store information like a computer does. It’s not a hard drive. There’s no one-to-one correspondence between things we’ve experienced and data points in the brain. Perception is not receptive, but active. That’s why we can have experiences and memories of things that didn’t “really” happen.

Our eyes take in 2D fragments and the brain renders them as 3D images. Furthermore, we take abstract concepts and assemble them into a perceived thing or situation. We don’t see “fire truck” so much as gather related details and then manufacture a fire truck. And if we’re focusing on the fire truck, we may not even notice the gorilla driving it.

Our ability to be conscious — to have that sense of what-is-it-like-to-see-something — depends on our awareness of our participation in perception. We feel ourselves putting it all together. And it’s the open-ended aspects of our experience that keep us conscious of our participation in interpreting them. Those confusing moments provide us with opportunities to experience our complicity in reality creation.

It’s also what allows us to do all those things that computers have been unable to learn: how to contend with paradox, engage with irony, or even interpret a joke. We don’t think and communicate in whole pieces, but infer things based on context. We receive fragments of information from one another and then use what we know about the world to recreate the whole message ourselves. It’s how a joke arrives in your head: Some assembly is required. That moment of “getting it” — putting it together oneself — is the pleasure of active reception. Ha! and aha! are very close relatives.