I was brought up short today by Alex Abramovich’s “Even When It’s a Big Fat Lie” in LRB, a review of Ken Burns’ Country Music, when I realized that I had been blithely ignoring the counterfeit nostalgia and encoded racism that clings to (or is perhaps at the core of) the genre. Music does carry multiple messages, serves various purposes, and is heard and interpreted in multifarious ways by different audiences and at different times. None of that should surprise—it’s just what Culture does, and there are cognate issues of the Dark Underbelly in Blues, in Rock’n’Roll, in the the various worlds of jazz, in “folk music” generally, and in High Culture musics too. There’s plenty of opportunity to descry the Emperor’s Clothes at work, and to call out various -isms on display, if that’s where one’s interests bloom.

My paths into these issues were via genres that might sustain the labels “ethnic” and “folk” and that partook of the early-1960s Harvard Square ferment so well documented in Eric von Schmidt and Jim Rooney’s Baby Let Me Follow You Down: The Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years. Robert Cantwell’s When We Were Good: The Folk Revival broadens the focus, and Scott Alarik’s Deep Community: Adventures in the Modern Folk Underground kicks out the jambs with a collection of 10 years of articles from The Boston Globe, which also ventures into English and Irish folk realms. Another dozen or so books on specific performers and groups clamor for inclusion in this canon, and may find their way in as we proceed.

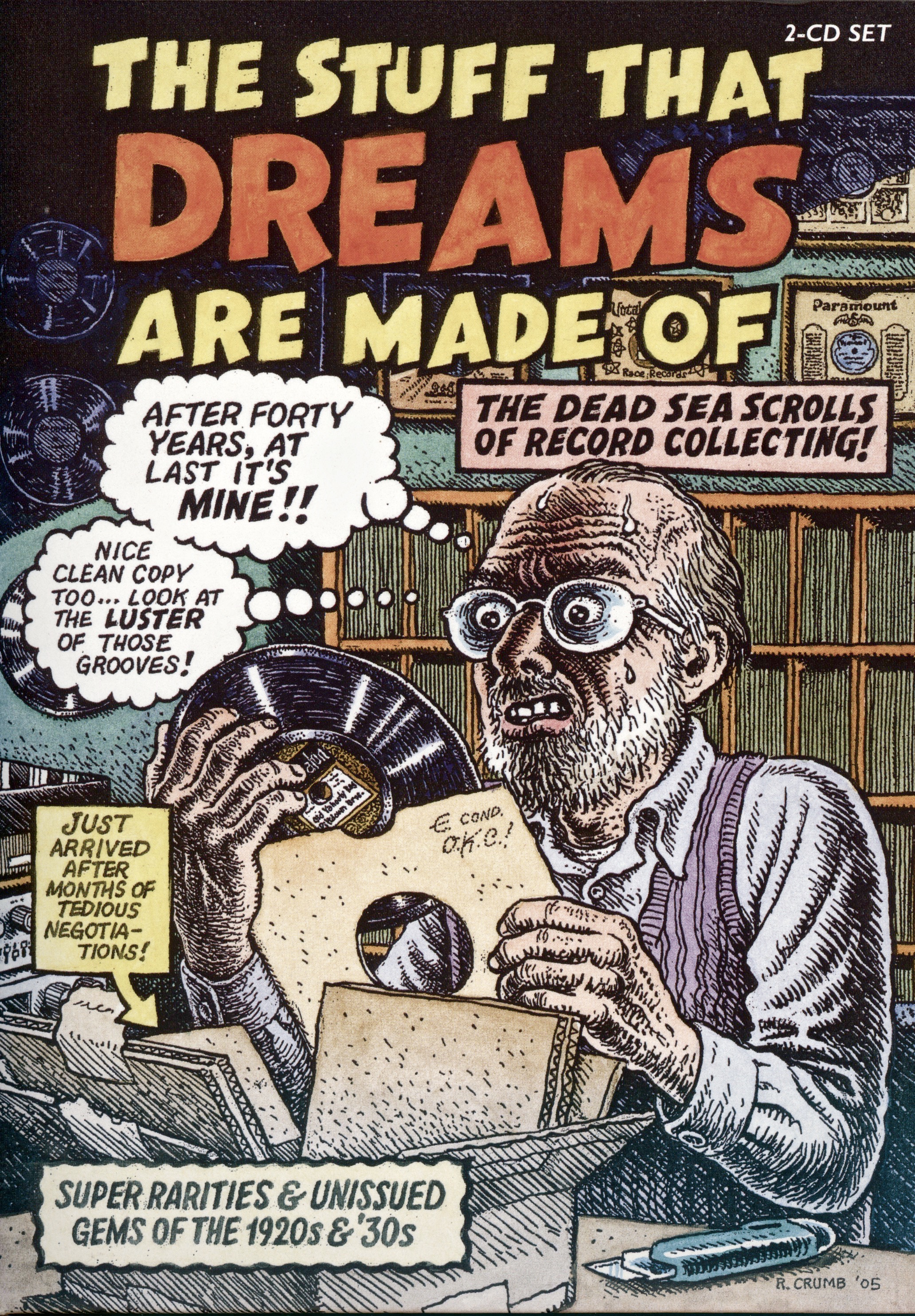

There are essential compilations of music, like Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music and its sequelæ and (most recently) American Epic (also a PBS video series). And scores of others, CD and vinyl, on my shelves. These are revenants of commercial 78RPM records from the 1920s and 1930s, remastered and alive again. Amanda Petrusich’s Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records is a fine introduction to the world of collectors, whose essence is skewered by R. Crumb (who is one of Them himself…):

Capturing the essence and visceral meaning of folk demands attack on multiple fronts, and John Szwed’s Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World is one port of entry.

…Alan’s public influence reached its peak between 1940 and 1960, when he was the single greatest force in bringing folksongs to American awareness… At times his influence can be seen in the distortions of the funhouse mirror of American culture, where a hard-fought idea can be perverted through the countervailing forces of social and technological interests and the discourse of fashion…

To those who knew Alan’s work only from his songbooks he seemed to be the pied piper of the folk, a kindly guide for a nostalgic return trip to simpler times.But he might have thought of himself as spokesperson for the Other America, the common people, the forgotten and excluded, the ethnic, those who always come to life in troubled times… those who could evoke deep fears of their resentment and unpredictability. At such times folk songs seemed not so much charming souvenirs as ominous and threatening portents. (pp 390-391; 3)

Robert Cantwell reflects on the experience of my own age cohort, we who were born during World War II:

…I remembered lovely Joan Baez, with her dark eyes and hair, her delicate shoulders, warbling to the plinking accompaniment of her guitar some British ballad in a voice somberly and exquisitely pure; images of Bob Dylan, the real inventor of punk, brazen, wasted, outrageous, excoriating racists and warmongers and capitalists in the drawling, swearing, muttering, doggerel-ridden songs we adored, and in the elliptic, visionary, lyrical ones that remade our world, but most of all felt again the defiant spirit in which we listened to them and the sense of strength and indomitability they gave us. (pg 15)

What wants explanation for me, and I trust to many of my readers, is the seven-year period between the release of the Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” and Bob Dylan’s appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 with an electric guitar and a blues band. These are artificial but not arbitrary points; by general agreement they mark the boundaries between which a longstanding folksong movement, with elaborate political and social affiliations, emerged out of relative obscurity to become an immensely popular commercial fad, only to be swallowed up by a rock-and-roll revolution whose origins, ironically, it shared. (pp 20-21)

[I] declare that folksong, whether high or low, old or new, traditional or original, survived or revived, refects the deepest and most persistent of human dreams, and marks the human face and human habitat with their power. Often it is poetically subtle and precise, melodically and harmonically striking and fresh, elegant formally and structurally sturdy and ingenious, in performance a source of lasting inspiration and intense joy. Within its basic simplicity there is, in execution especially, a complexity that will always defy analysis. (pg 44)

The tunes I still attempt to play, the recordings that moved me, this or that unforgettable performance, have assumed over time nearly the status of persons—like brothers or sisters, perhaps, in whom one inevitably catches the old family resemblance, with whom one can always become reacquainted, in whom time collapses in upon itself, and yet who must finally remain independent, other, unconquerable. We cannot, finally, abandon them—for as surely as we must relinquish our youth, so must we honor and sustain the life force that is the gift of youth. As in any youth movement, what drove the folk revival was sheer erotic magnetism and beauty, idealism and aspiration, personal, social, and political striving, forces that, perhaps more than any other art, music is capable of communicating. (pp 45-46)

And von Schmidt and Rooney capture the feeling in the Cambridge air at the start of the 1960s:

Listening to music and trying to play and sing a few songs started to become more important than whatever was going on in school. For some it became a passion that started to smoulder inside. It was at this point that certain individuals made a difference. Some were teachers, some were organizers, some were sources of energy, instigators, and others were simply talented, musically gifted.

So, where no scene had existed before, one came into being. What had been smouldering before burst into flames. Jan Baez was the most prominent member of a group whose numbers were growing daily, as were their abilities as musicians and performers. More important still was the fact that there was an audience for this music. People wanted to hear it. It filled some need that we all shared in common before we ever knew what it was. Whatever plans we might have had before were to be totally changed. (from the Foreword)

Quintessential for me has been the New Lost City Ramblers: Mike Seeger, John Cohen, Tom Paley (replaced in 1963 by Tracy Schwarz). The Early Years 1958-1962 is a good introduction, and the liner notes are an essential accompaniment. An extract:

The New Lost City Ramblers will leave barely a blip in the history of the entertainment business, as they predicted in their jokes about their “long-playing, short-selling” albums on the Folkways label. But they have nevertheless earned the touch of immortality for their central role in our discovery of the folkloristic riches preserved electronically in the early years of our century. As individual performers, Mike Seeger, Tom Paley, and John Cohen had during the 1950s become interested in performance style in American folk music, exactly that dimension of the music which recordings uniquely capture. In 1958 they formed The New Lost City Ramblers with the explicit intention of performing American folk music as it had sounded before the inroads of radio, movies, and television had begun to homogenize our diverse regional folkways.

They studied and learned from commercial 78 rpm discs of “hillbilly” musicians recorded in what has come to be called the Golden Age (1923–1940), from blues and “race” records of the same era, from the bluegrass recordings of the post-war period, from the field recordings on deposit in the Library of Congress. In turn, they began their own field trips to seek out and record and learn the music of older rural musicians who still played and sang in the old way. Over the next twenty years, the Ramblers poured forth a steady stream of their own performances live and recorded, albums of their field recordings, and festival performances and workshops in which they introduced musicians they had met in the South to urban audiences of the folk song revival of the 1960s. Their lasting influence was greatest upon a relatively small but important part of that urban audience—those few who wanted not only to study the music seriously, but who also wanted to learn to play the music themselves, actually to be the heirs of a musically rich American culture which by the 1960s largely existed only in the scratchy echoes found on primitive recordings, and in the memories of an ever-fewer number of elders.