Geoffrey Hughes’ Words in Time: A social history of the English vocabulary(1988) offers a different take on space-and-time and language, centered on the notion of semantic fields (“containing those words or meanings which cohere around a particular concept, topic, or thing”).

The book’s dedication says

all workers

at the alveary

It was the work of a moment to ask the online OED about ‘alveary’, and so to discover

Origin: A borrowing from Latin. Etymon: Latin alveārium.

Etymology: classical Latin alveārium...

1.

a. A repository, esp. of knowledge or information. Originally as the

name of a dictionary encompassing several languages. 1574—1983

b. A beehive. Also: the location where a beehive stands; an apiary.

Now rare. 1623—1918

†2. A hollow in the external ear in which earwax collects; (also) the

external auditory canal. Obsolete.

The book itself begins with a quotation from Owen Barfield (who was, with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, a member of the Inklings):

It has only just begun to dawn on us that in our own language alone, not to speak of its many companions, the past history of humanity is spread out in an imperishable map, just as the history of the mineral earth lies embedded in the layers of its outer crust. But there is this difference between the record of the rocks and the secrets which are hidden in language: whereas the former can only give us a knowledge of outward, dead things—such as forgotten seas and bodily shapes of prehistoric animals and primitive men—language has preserved for us the inner, living history of man’s soul. It reveals the evolution of consciousness.

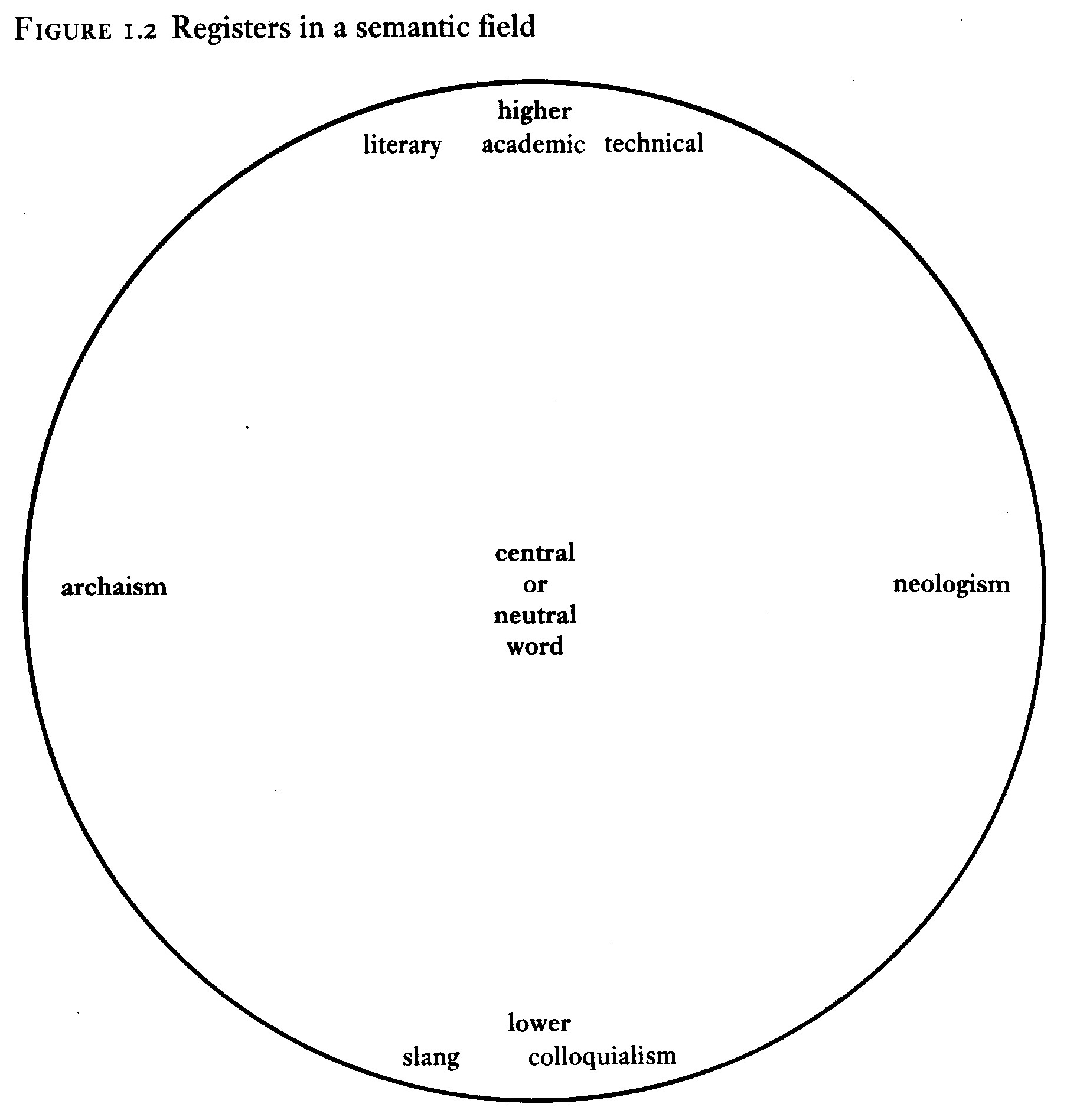

Hughes is primarily concerned with words as “semantic legacy” (e.g., of the Middle Ages, of the Growth of Capitalism, Journalism, Advertising, Ideology and Propaganda), and he presents words identified as belonging to semantic fields schematically, as circles showing registers of terminology:

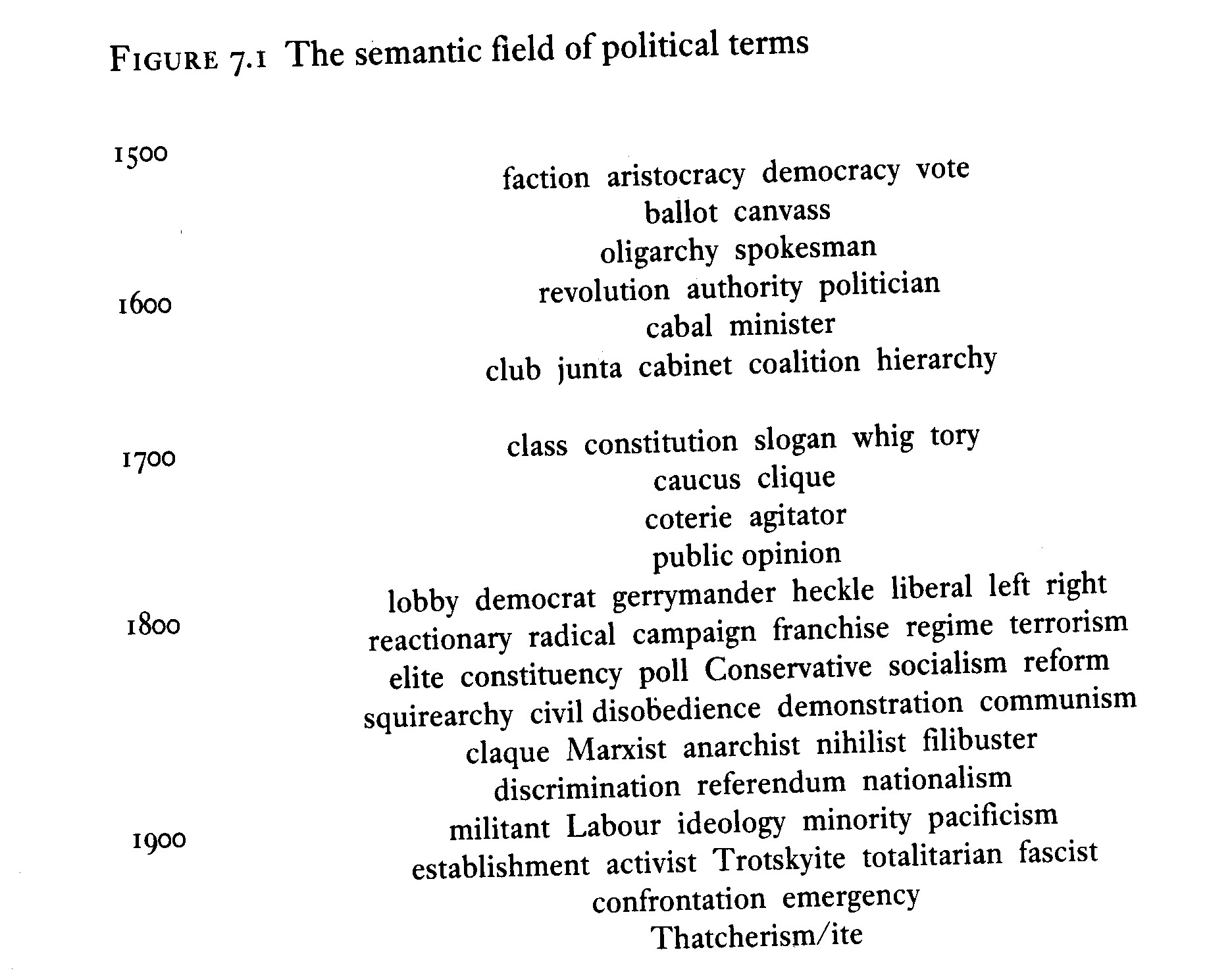

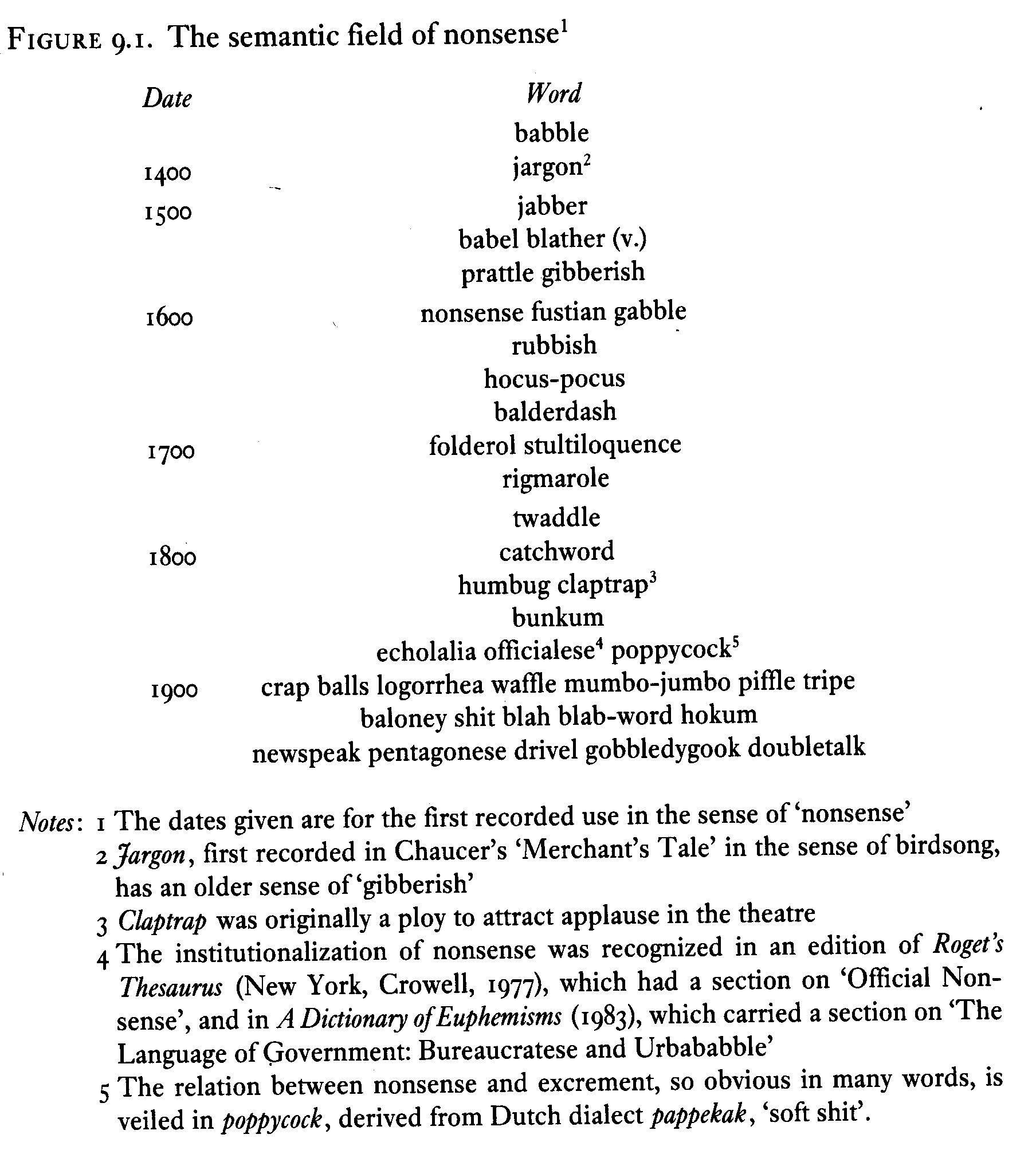

and, for example,

and in tabular and chronological form:

The last thirty-plus years is a long time in lexicographical evolution, and in 2020 Hughes’ approach seems rather fusty and even a bit pedestrian; the online version of the OED produces more detailed versions straight out of the box, with dates and quotations, and yields nicely built collocations of terms in the Thesaurus mode. It’s still a pleasure to sample the pages of Words in Time for the odd bits that delight word hounds, and for the discursive style of a bygone era:

For centuries purchase meant something far more rapacious and disorderly than the present transactional sense denotes. The old senses of purchase, dating in ME from c.1297, were derived from chase and revolved around the actions of hunting and taking by force, whether the object were prey, person, plunder, or pelf. (In Old French an enfant de porchas was not, as one might suppose, a child adopted or ‘purchased’ in slavery, but an illegitimate.) These meanings reflect an ancient, primitive time when de jure and de facto possession were often difficult to distinguish, more so than today. The original strong physical sense of purchase, we observe is still used in contexts of leverage in physics and engineering.

To appreciate that 30-plus years’ distance in register, compare with A “Let’s Circle Back” Guy.