What a magnificently English opening sentence:

Whether or no, she, whom you are to forgive, if you can, did or did not belong to the Upper Ten Thousand of this our English world, I am not prepared to say with any strength of affirmation.

What a magnificently English opening sentence:

Whether or no, she, whom you are to forgive, if you can, did or did not belong to the Upper Ten Thousand of this our English world, I am not prepared to say with any strength of affirmation.

I read a fair bit of the increasingly panicked College Disgruntlement/Higher Education Futures stuff, and there’s a vast gulf between the Now and what I experienced 50 years ago… and even a pretty deep canyon between the Now and what I retired from a decade ago. In the landscape of cutbacks and Queen Sacrifice I see nothing that evokes hopeful feelings, and much that suggests that the Way, once seemingly so clear, has been lost irredeemably. The latest case in point is John Warner’s The Problem ASU is Solving, which ends thus:

…we should be clear, in a culture of free-market competition, where education is increasingly viewed as a private, rather than public good, and states are moving to divest themselves of the responsibility to support their public institutions, this is the future for those of us who will not be able to afford entry into what we will come to think of as the “legacy[3]” higher education system.

ASU’s moves like the edX initiative, or Starbucks partnership, are absolutely rational, probably even savvy in the culture we have constructed. They will likely be cheered by Wall Street and Silicon Valley because they present more opportunities for markets that can be disrupted and monetized.

That’s what we should be most terrified about.

[3] I use this word to connote multiple meanings, including the notion that only the children of the already educated, the legacies, will likely have access to such places.

Being about to participate in a multi-day 50th Reunion event at which the glories of a (perhaps the…) premier institution will be trumpeted (and alumni contributions solicited), and where symposia on the menu include “The Awakening of Wisdom–How Do We Experience and Practice It?” and “The Challenge of Taking Collective Action–Societal Meaning” … well, I’m struggling to get the whole thing to come into focus. Maybe I’ll encounter some Wise classmates, and surely there are quite a few who still have faith in Collective Action, but I don’t aspire to membership in either category. Best I can do is to resolve to play at participant observation, making notes and gathering data.

The strangest things float through the mind unbidden. As we were driving back from a day at Acadia National Park, the phrase “he shot him into doll rags, naturally” drifted in and then out again. Mmmm, I thought, I know I read that somewhere sometime… but how could I find it again? 20 years ago it would have been impossible, but with Google a search for “doll rags naturally” got one single hit, a certified BINGO: IF Science Fiction March 1961, in a story by Julian F. Grow, “The Fastest Gun Dead” … I was a high school senior then, and must have happened on that issue of the mag (though I don’t remember doing so), or maybe I read it a couple of years later in 7th Annual Edition: The Year’s Best S-F (1963).

I don’t advise a Google search for “doll rags shot” (too many distressing results, pro- and anti-gun). Take it from me that the phrase means lots of little bits…

I’m still processing our visit to the Qu’est-ce que la photographie? exhibit at the Pompidou, and looking forward to the arrival of the catalog (ordered via Amazon) and the challenge of reading the French text that accompanies the images.

Consider two rather startling images, neither of which was familiar to me (and I’d never heard of the photographers either, which just goes to show my own insularity):

Neither is quite what it seems at first glance, and the viewer struggles a bit before catching on.

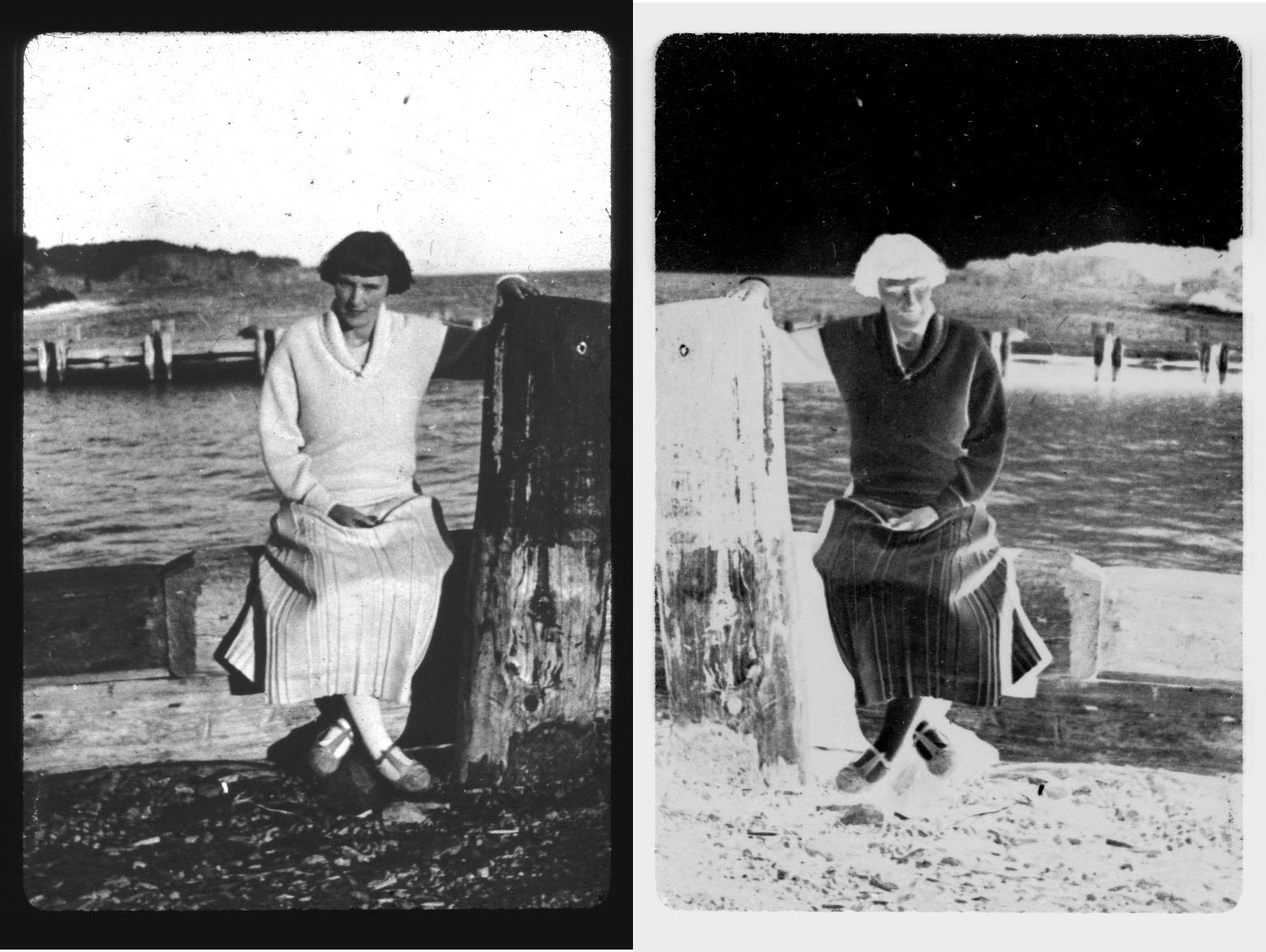

Mulas inverts tonalities and flips horizontally: one hand becomes two. Rautert tweaks a single negative to represent two different celestial bodies.

It’s interesting to explore the notion that multiple renderings of an image can disclose things hidden or obscured in any one version, and the kindred idea that any photograph is potentially many photographs. Where does ‘truth’ or ‘reality’ lie? Is our perception of an image all subjective prevarication?

Digital tools put these questions at the ends of our fingers.

Inversion of tonalities and mirror-imaging are two techniques that are easy to play with using GIMP, and I’ve done quite a bit of that as I’ve explored tessellations of Betsy’s and my own images (see some examples and a few more). Is such manipulation merely a gimmick, or is there something more to it? This is a question that comes up often in the world of Art, and I’m learning to enjoy the ambiguities and widen my purview.

An interesting challenge came my way shortly before we left for France, as I read through the announcement of an exhibit that will open soon at the deCordova Museum in Massachusetts: Integrated Vision: Science, Nature, and Abstraction in the Art of Len Gittleman and György Kepes. Len Gittleman was our teacher in 1963-1964, and we revere him, but the description of the show brought me up short:

Gittleman’s Lunar Transformation portfolio is a series of ten vividly colored serigraphs created from black and white photographs taken during the Apollo 15 mission to the moon in 1971. Gittleman’s discerning use of color transforms the craters and crevices of the lunar surface into vibrant, colorful abstractions which aesthetically parallel the art movement of Abstract Expressionism. The serigraphs’ strong graphic presence reflects the awe-inspiring nature of their source material.

Wait a minnit, I found myself thinking, that’s not photography… and then I heard myself and had to laugh at stick-in-the-muddism. Of course it’s photography, just maybe not the comfortable and predictable sort that I know I like…

As I’ve suggested in recent posts, visiting the Griffin Museum and Florence Henri and Qu’est-ce que la photographie exhibits has been ramifying across my own photographic life. This morning I woke up thinking about alternative presentations of an image that’s been a conundrum for me over more than 40 years: Poor Alice G.. I remembered that I’d once scanned a slide of the photo, but happened to reverse it, and I thought well why not? …and so

Remember to breathe…

All those years ago I was drawn to Anthropology because I thought it was a comprehensive and comprehensible way to MAKE SENSE of the world around me; and in my years as a prof I approached teaching Anthro in the same spirit, looking at the great variety of solutions to the practical problems of living that people had developed over the vastnesses of time and space (well, 10,000 years or so; and terrestrial space, but still…), returning again and again to the observed Fact that the Emperor was Naked. And now I find myself looking to one particular/peculiar strain of the discipline to, once again, [try to] make sense of the contemporary world.

Lately I’ve been reading a number of things that have fundamentally the same message. Much seems to emanate from David Graeber, and is concerned with bamboozlement in many forms:

…a kind of strategic pivot of the upper echelons of US corporate bureaucracy — away from the workers, and towards shareholders, and eventually, towards the financial structure as a whole… corporate management became more financialized, but at the same time, the financial sector became corporatized with investment banks, hedge funds, and the like largely replacing individual investors. As a result the investor class and the executive class became almost indistinguishable… (19)

…the last two centuries have seen an explosion of bureaucracy, and the last 30 or 40 years in particular have seen bureaucratic principles extended to every aspect of our existence… (27)

What was being talked about in terms of “free trade” and the “free market” really entailed the self-conscious completion of the world’s first effective planetary-scale administrative bureaucratic system. (30)

…public and private bureaucracies finally merged together in a mass of paperwork designed to facilitate the direct extraction of wealth. (35)

If one gives sufficient social power to a class of people holding even the most outlandish ideas, they will, consciously or not, eventually contrive to produce a world organized in such a way that living in it will, in a thousand subtle ways, reinforce the impression that those ideas are self-evidently true. (37)

…what we call “the public” is created, produced through specific institutions that allow specific forms of action — taking polls, watching television, voting, signing petitions or writing letters to elected officials or attending public hearings — and not others. (98)

(The above from The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. There’s much more I’d transcribe from Graeber’s writings, including Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology and of course Debt.

A similarly resonant voice: Tariq Ali in the latest London Review of Books:

The New World Disorder (Vol. 37 No. 7 · 9 April 2015)

But social democratic reforms have become intolerable for the neoliberal economic system imposed by global capital. If you argue, as those in power do (if not explicitly, implicitly), that it’s necessary to have a political structure in which no challenge to the system is permitted, then we’re living in dangerous times. Elevating terrorism into a threat that is held to be the equivalent of the communist threat of old is bizarre. The use of the very word ‘terrorism’, the bills pushed through Parliament and Congress to stop people speaking up, the vetting of people invited to give talks at universities, the idea that outside speakers have to be asked what they are going to say before they are allowed into the country: all these seem minor things, but they are emblematic of the age in which we live. And the ease with which it’s all accepted is frightening. If what we’re being told is that change isn’t possible, that the only conceivable system is the present one, we’re going to be in trouble. Ultimately, it won’t be accepted. And if you prevent people from speaking or thinking or developing political alternatives, it won’t just be Marx’s work that is relegated to the graveyard. Karl Polanyi, the most gifted of the social democratic theorists, has suffered the same fate.

and this announcement by William Arkin, via Gizmodo, of a Twitter feed covering a lot of the same dolorous but important ground:

o here’s what I plan to do: Expose. Explain. Secrecy and euphemisms are carpet-bombing us into submission. I’m sick of the parameters of the sanctioned debate. So instead I will try to treat the secret world like a sports league: There are coaches, players, commentators, bookies, and marketing geniuses. We’ll have something to say about all of them, something to reveal every week. The teams are the NSA, the CIA, FBI, Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, Department of Homeland Security, TSA, ICE; and that’s just Division I. There’s a Division II playing somewhere else, far more obscure but nevertheless influential and odious, populated by billion-dollar institutions like the Counter-Narcoterrorism Program Office or the Defense Threat Reduction Agency or U.S. Army North, real parasites on the American spirit, survivors because what they do festers in the dark. Each has a history and personality, a lineup, a budget cap, a general manager, a narrative to sell.

(much more and very worth reading)

Here’s another photograph that hits the mark. We were walking around Paris just as the sun was setting behind dramatic clouds and I looked up and there it was:

Sometimes it’s a bit of text, sometimes a phrase in a tune, sometimes a (photo-)graphic, but the experience is pretty much the same: a brief guffaw loosed at the sheer excellence/audacity/brio of the thing. Case in point, this from the end of a piece by Charles Simic, from New York Review of Books, which just rolled in via RSS:

Here, to give you an idea, is the beginning of a story called “Water Liars” from a collection of [Barry Hannah’s stories] called Airships:

When I am run down and flocked around by the world, I go down to Farte Cove off the Yazoo River and take my beers to the end of the pier where the old liars are still snapping and wheezing at one another. The line-up is always different, because they are always dying out, or succumbing to constipation, etc., whereupon they go back to the cabins and wait for a good day when they can come out and lie again, leaning on the rail with coats full of bran cookies. The son of the man the cove was named for is often out there. He pronounces his name Fartay, with a great French stress on the last syllable. Otherwise, you might laugh at his history or ignore it in favor of the name as it’s spelled on the sign.

I’m glad it’s not my name.

This poor dignified man has had to explain his nobility to the semiliterate of half of America before he could even begin a decent conversation with them. On the other hand, Farte, Jr., is a great liar himself. He tells about seeing ghost people around the lake and tell big loose ones about the size of the fish those ghost took out of Farte Cove in years past…

Having previously read the story and knowing what was coming, reading this far was all that was required for my purpose, which was to close my eyes and go to sleep with a smile on my face.

Maybe epiphany is a sufficiently weighty word to bear this freight of delight. I guess I could say that I live for such moments of glee, and this one sent me directly to Amazon to snag Hannah’s book on the Kindle.

A photographic example from the just-concluded trip to France is another suchlike, a scene I glimpsed for just a moment while ankling around in Pont-Aven (on the south coast of Brittany) and had the wit to capture:

addendum: it occurred to me to try a bit of manipulation, inspired by the Qu’est-ce que la photographie? exhibit:

Yesterday we visited the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester (the town in which Betsy grew up) to see the exhibit Photography Atelier 21. The photographs themselves were pretty inspiring, and the presentation was stunning, but the ‘artist statements’ accompanying the images were the real revelation for me. I’ve previously limited my image of such statements to introducing the photographer, rather than contextualizing the images, and the new perspective started me thinking anew about several of my own photographic projects.

I especially admired the work by Dianne Schaefer and James Hunt, both of which used infrared digital cameras (Schaefer’s Blurb book The Light You Cannot See really eponomizes the medium and technique).

We’re planning to visit a couple of photographic exhibits in Paris in the next few days: Qu’est-ce que la photographie ? at Centre Pompidou and Florence Henri at Jeu de Paume, and anticipate further inspiration.

I’ve just snagged Why It Does Not Have To Be In Focus: Modern Photography Explained which looks like it will further enlarge my thinking about what I’m doing with photography.

I found this grumble I’d written 11 years ago, as I followed links in the hypertext mentioned in the last post. Still find it relevant:

Innovation

at small liberal arts colleges

is all but dead

except for independently/externally funded efforts

and rogue actions.

Administrations have insulated themselves

behind a smokescreen of

‘strategic planning’

which privileges risk avoidance

in the name of ‘management’.

Add more deans,

institute performance reviews,

emphasize assessment of instructional objectives.

Distrust visionaries.

Reduce creativity and experimentation with unpredictable outcomes.

Recline upon past laurels.Faugh.

Every five years my Harvard class publishes a volume of Class Reports, and this year is the 50th. I sent a brief submission for the book and included a link to an expansion, a pretty elaborate hypertext document that I’ve been working on for the last couple of months. I have no idea if others will explore its labyrinthine wanderings, but somehow that matters less than that I’ve managed to piece together into quasicoherence all sorts of elements of what I’ve been doing and thinking about since 1965. Such things are never finished, and I keep going back to tuck in further links and add bits of text, so the document will continue to evolve. The Reunion itself in in late May, and [quite uncharacteristically] I’ve signed up to attend. I hope for something more than paunchy bonhomie with people I never knew back in the day, but many of those I did know are either dead or constitutionally averse to Reunions. We shall see…

Meanwhile, we’re about to depart for two weeks in France, one of them in Brittany. Many photos will doubtless ensue.