I’m reading Guy Tal’s More Than A Rock: Essays on art, creativity, photography, nature, and life and Richard Zakia’s Perception and Imaging: Photography – a way of seeing, in preparation for the workshop with Andy Ilachinski, and I’m currently embroiled with the vexed question of whether what I do with photography is art. On the one hand, it just doesn’t matter what the answer to that question is, since I’ll keep on doing it anyway, and don’t got to show no stinkin’ badge. But on the other hand, the answer might be NO, in that I don’t choose to wrap my doings in the garments of pretense, or engage in invidious comparison, by staking a claim as an Artist and seeking a public. I’ve been here before, with respect to my identity as a musician (I play mostly for myself, avoid performance, but take pleasure in being recognized as skilled), with many of the same insecurities.

Here’s a passage from Guy Tal that has me wondering if I could possibly live up to what he invokes:

Being an artist is about living passionately and deliberately, placing curiosity and awe and honesty and significance above social conventions, celebrity, and material spoils. It is not about finding interesting anecdotes, but about discovering them within, creating them anew, elevating and sharing and celebrating them in defiance of all that is corrupt and cynical and cruel and bigoted and shortsighted… (pg 37)

But if what I do is not art, what IS it? Most of my images have some narrative purpose, or seem to me to evoke stories of some sort; but generally the stories come from the images, or fit into some larger narrative project as exemplars (e.g., all those gravestones, or all those Abandoned Ancestors). Something prompts me to frame and click, and once I see the result in post-processing, a story may emerge that seems to explain something about the image. An example from the Acadia National Park adventure:

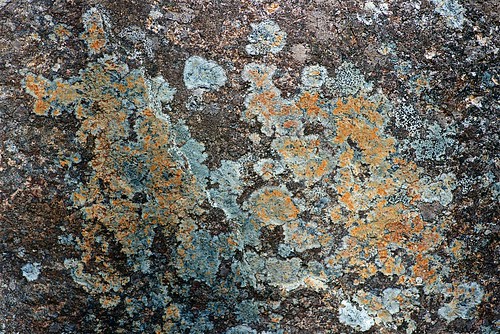

Lichen on rock. Just an interesting pattern that fit happily within the field of view of a 100mm macro lens, no obvious expository insight in the viewfinder. But as soon as I saw it on the computer screen, the notion of Pursuit couldn’t be unseen: the figure on the left side, sharply defined by a line of white sketching its back, with an outstretched arm showing the direction of movement, is obviously being chased by the marvelously indistinct figure on the right, whose whitish feet (in the lower right corner) are clearly running… T’ang Dynasty, perhaps? Susurrus of silken robes? The art might be in the happenstance of lichen growth on granite substrate [not MY circus, not MY monkeys], or in the accident of my framing [definitely MY circus], or it might reside entirely in the post-hoc tale-making [positively MY monkeys]. It’s difficult to imagine that a print of the image, matted and framed and hung on a gallery wall, would have any salience for viewers without the interpretation.

And just why does any of this matter? It’s those daunting but fascinating books, along with a bunch of others in realms of photographic history and aesthetics, that pile up around my reading chair. They keep nudging me to explore further, but also remind me that I’m in search of my own vision. Sure, Stieglitz photographed clouds and made them into Equivalents, connecting them to his own mental states:

A symbolist aesthetic underlies these images, which became increasingly abstract equivalents of his own experiences, thoughts, and emotions. The theory of equivalence had been the subject of much discussion at Gallery 291 during the teens, and it was infused by Kandinsky’s ideas, especially the belief that colors, shapes, and lines reflect the inner, often emotive “vibrations of the soul.” In his cloud photographs, which he termed Equivalents, Stieglitz emphasized pure abstraction, adhering to the modern ideas of equivalence, holding that abstract forms, lines, and colors could represent corresponding inner states, emotions and ideas. (from The Phillips Collection)

Doesn’t mean I should or shouldn’t photograph clouds, does it? Or see/not see things in them that aren’t “pure abstraction.”