Last week’s visit to Boston Museum of Fine Arts to see the Sheeler and Stieglitz shows, all images drawn from the MFA’s Lane Collection, reminded me of the book An Enduring Vision: Photographs from the Lane Collection which I bought a couple of years ago after an earlier visit to the MFA. I sat down to read Lyle Rexer’s introductory essay, “A Widening Circle: some images from the Lane Collection” and was brought up short by the eloquence of its first paragraph, which seems to directly address issues I’ve been thinking about:

Photographs are perhaps the most peculiar art objects because their invitation, apparently so literal, is really open-ended. Severed from the flux of temporal experience in which they originate, increasingly cut off from the rich context of historical meanings as the moments and situations they capture recede in history’s rear-view mirror, all photographs are orphaned, telling us, as Diane Arbus once remarked, everything and nothing. At the same time, the simple fact of putting a frame around a scene can suddenly invest its contents with urgency, demanding we pay attention to a set of visual relations that might otherwise have gone unnoticed—or that in truth did not even exist until time was stopped and they were framed. In a photograph it can seem as if the world is speaking to us directly of some truth, but that truth is obscure and hard to decipher, like an oracle. In the presence of a mystery that hides in plain sight, photographs solicit us to provide captions, to invest our own surmises and explanations, our own stories. (pg. 25)

Rexer goes on to tie together a number of the dominant figures of 20th century American photography, and points to a Bullock image I’ve never had occasion to study before:

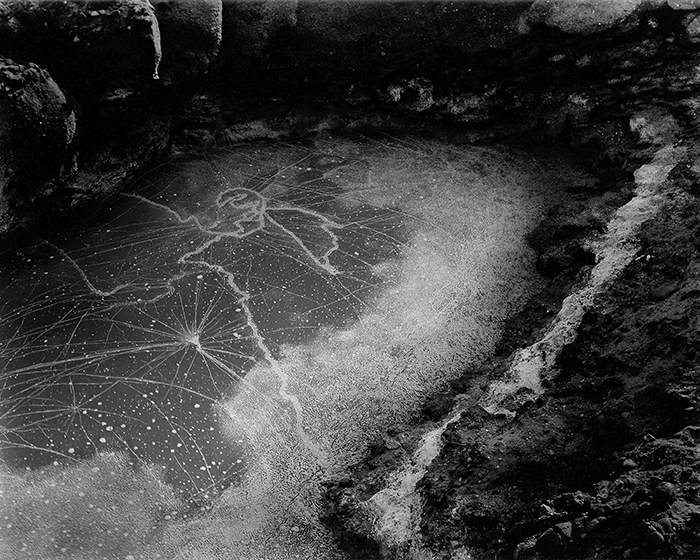

(Adams, Weston, White, Sommer, Bullock, Sheeler) …all shared the notion that form is a universal constant of the world and our experience, the expression of a fundamental principle of order uniting all levels of phenomena. Form is inherent in the nature of things but obscured by circumstance. It is identified by the intuition of the photographer and fixed objectively in the composition and attributes of the photograph. The expressive photograph, then, is one that mediates a recognition of connectedness between the viewer and the greater order of the world through the artist’s artistic sensibility. The meaning of the photograph is open-ended in that it suggests connections that can be both psychological and natural, if not spiritual, as in Wynn Bullock’s famous Tide Pool (1957), an image that sets up a chain of associations from the microscopic to the heavenly. Specific place and time, the anchors of photographic reference, are only points of departure. (pg. 26)

(snagged at

http://wynnbullockphotography.com/featured/2013-01/images/pointlobostidepool700.jpg)

This photograph reminds me that I’m forever finding new photographs and photographers to explore, and thus greatly complicating the question of what/who my favorites might be. This is a good thing, and not a bad thing.

Another realization: I’ve always been mostly interested in photographs and their social and historical context, and never had occasion to think much about collectors of photography, who these days pretty much have to be deep-pocketed high-rollers. I begin to see that I might owe a debt of gratitude to those who underwrite my pleasures by their support of artists and the museums that acquire their works.

So I googled Lyle Rexer and found The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography, and (almost needless to say) ordered a copy. Will it ever end?