A couple of days ago I awoke with the question of just who is responsible for the idea that a sculptor liberates a figure from within a block of stone by removing material. It turns out to be Michelangelo:

Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.

(photo by Jörg Bittner Unna, Wikimedia Commons)

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

For Michelangelo, the idea was already there, inside the hunk of stone,

whether by divine providence or his own imagination.

His eyes and hands were merely the vessels by which that idea—the art—was brought forth

into the physical world as he or God (or both) originally intended.

(https://medium.com/@nilsaparker/the-angel-in-the-marble-f7aa43f333dc)

*****

And a few days ago I ordered Chris Rainier’s new book Mask, thinking that it would assist in threading together elements I’ve been juggling as I assemble materials for the next Blurb book. Pico Iyer’s Introduction has some very useful perspectives:

(of an owl mask he had bought in Bali) It wasn’t just a mask… It carried a whole universe, a swarm of roiling forces, within. I really couldn’t tell if the spell it cast was happy or malign… All I did know was that it belonged to the realm of the spirit, the world of transformation…

…an agent of transfiguration, which allowed whoever wore it to become something other, belonging to the sphere of angels and demons.

In Africa, I knew, different kinds of masks signified the ways in which another world could enter our own, liberating our minds from the conscious realm into something no less real but much less easily tamed.

Masks are not just a portal to another world, but a reminder of the fact that our lives are defined by amazement and terror and silence. Just to see a mask is to travel out of the everyday into another, a more secret realm.

I’m still trying to figure out in what way my life might be “defined by amazement and terror and silence”, but the rest is surely pure gold, and suggests to me some new ways to think about the rocks I’ve been photographing: they are in a sense sculptures, and they have some of the Powers that are built into masks.

*****

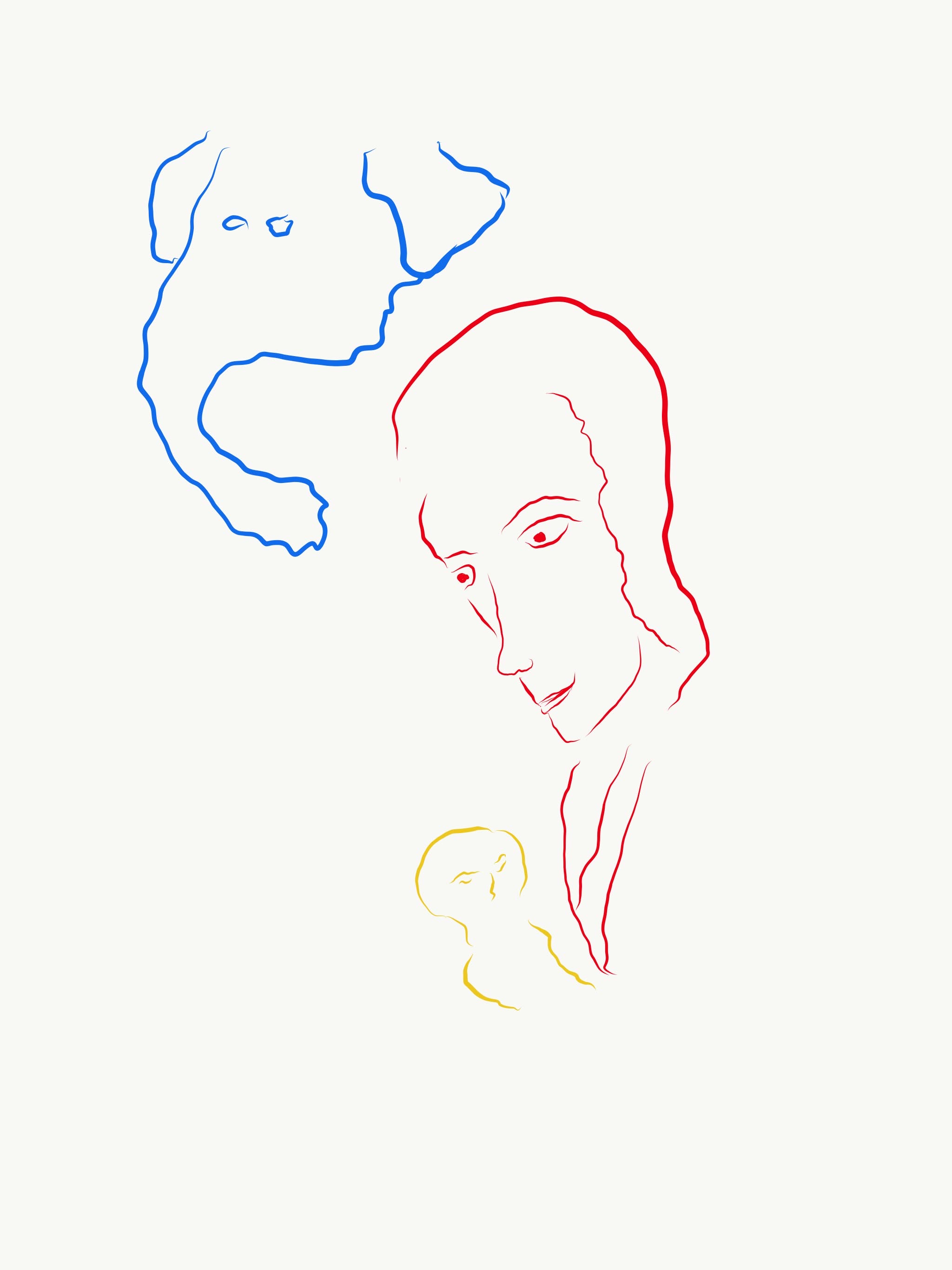

A story in this morning’s New York Times, Mythical Beings May Be Earliest Imaginative Cave Art by Humans, surfaced the word Therianthrope just when I needed it:

In the story told in the scene, eight figures approach wild pigs and anoas (dwarf buffaloes native to Sulawesi). For whoever painted these figures, they represented much more than ordinary human hunters. One appears to have a large beak while another has an appendage resembling a tail. In the language of archaeology, these are therianthropes, or characters that embody a mix of human and animal characteristics.

***

Therianthropy is the mythological ability of human beings to metamorphose into other animals by means of shapeshifting. It is possible that cave drawings found at Les Trois Frères, in France, depict ancient beliefs in the concept. The most well known form of therianthropy is found in stories concerning werewolves.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Therianthropy)

Quite a few of my rock creatures occupy territory between human and creature, and it occurred to me that

Therianthropes guard the bridge

between the risible and the numinous

a formulation that is just too delicious as a description of part of the landscape I’m dealing with. So now I need to find some examples. And today being the first day it was cold enough for ice to form on the ponds at Drift Inn, we went to see if there were photographs to be made. Indeed:

and one from the recent Nova Scotia trip:

I won’t attempt to calculate the risibility and numinosity quotients of these, and only the lattermost seems to rise to the level of full-on therianthropy (and it’s probably a dryad anyway).