J.R.R. Tolkien filled a yawning gap in the Lexicon by rescuing and repurposing the Old English word maðm (see Michael Quinion’s explication):

Anything that Hobbits had no immediate use for, but were unwilling to throw away, they called a mathom. Their dwellings were apt to become rather crowded with mathoms, and many of the presents that passed from hand to hand were of that sort.

(The Fellowship of the Ring, pg ?)

Many are they who have appropriated the term for their own use, for the very good reason that it’s an efficient descriptor for a universal household problem –indeed, for an information management quandary that is an inescapable facet of ubicomp. A lovely instance of hackerspeak exemplifies:

This file contains mathoms, various binary artifacts from previous versions of Perl. For binary or source compatibility reasons, though, we cannot completely remove them from the core code. (Rafael Garcia-Suarez).

Gardner’s Dispatch from EDUCAUSE has been echoing in the halls of my mind all day:

There is indeed a “delight in social archiving.” A very fine phrase from Dr. Alexander. My reflection: we can all make not only civilization’s library, but civilization’s magic attic, the place where the intimate, uncanny cabinet of wonders stands in the corner, awaiting our exploration.

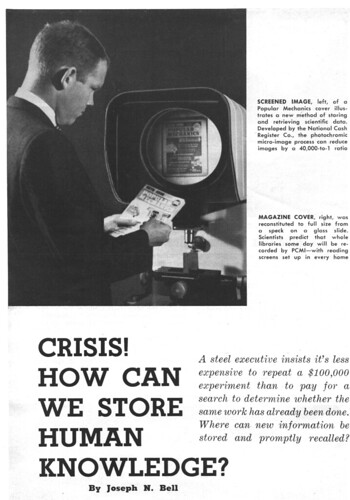

…but it was a chance encounter with an article in the November 1962 issue of Popular Mechanics

that nudged me to realize how mathoms fit into the picture. The article is a real hoot of clumsy technologies, which I remember all too well:

Micro-images could also be used to revolutionize libraries as we know them today. With micro-images, an entire library could be reduced to a single filing cabinet of three-by-five cards. These cards are expected to be so inexpensive to reproduce that the reader could afford to keep them. (pp. 109-110)

and I can’t resist quoting the penultimate paragraph for its oystery Cold War ethos:

A good many thoughtful Americans are wondering whether or not we still have the prerogative of proceeding slowly in the area of data storage and retrieval. Allen Kent, associate director of the Center for Documentation and Communication at Western Reserve University, said recently, “The Soviet Union has mounted a massive effort to ‘brainpick’ the world’s recorded literature in order to assure a more effective scientific and technical effort on their part. We, too, must go in this direction, and our ‘brainpicking’ efforts have been desultory.” (pg. 224)

…and how can I possibly resist adding this illustration?

So hobbits and Bryan and Gardner and brainpicking. Where is all this headed? We are, in our fumbling and semi-conscious ways, building that “intimate, uncanny cabinet of wonders” and figuring out what its uses might be. For me this is an adventure in sorting out a lifetime’s accumulation of STUFF, of THINGS that need to be arrayed, identified, glossed, indexed, tagged, narrated, contextualized, interpreted, juxtaposed …in short, Made Accessible. The tools seem to be at my fingertips, though the overall Scheme still eludes me –or perhaps there doesn’t need to be a Scheme for the Mathom House. And I can’t help but wonder: is there any reason to think that our efforts won’t look just as silly 45 years hence?