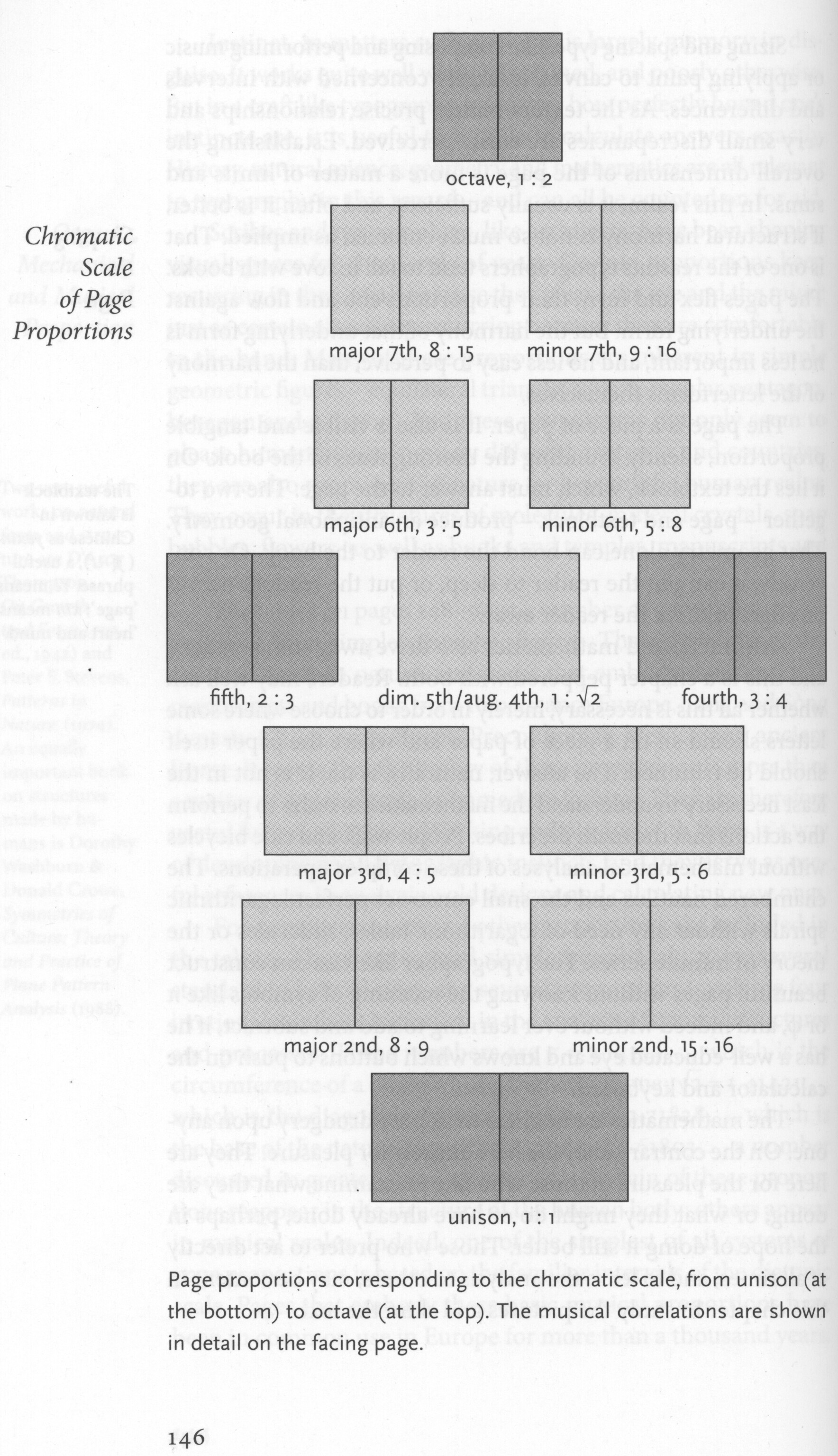

Some photos seem promising in the viewfinder, but once displayed on the computer screen turn out to be underwhelming. I can see what I was after (but didn’t achieve) with this one, but didn’t process it further in the first round:

It was only later in the day, when I was considering possible symmetrical unfoldings among the day’s photographs, that it occurred to me that this one might be a candidate for the GIMP copy-flip-join treatment. I observe that my previsualization of the effects of this procedure is chancy at best, in that I’m usually surprised at what the transformation reveals, and I don’t often make exposures with the intent to produce symmetrical arrays of the resulting images. The products are mostly serendipitous.

Anyway, the result of the transform opened a whole new world of interpretation for the image, and my first thought (and hence the title of the image) was “empty wings”.

Now, wings don’t usually have the property of emptiness or fullness; they may adorn the backs of angels and mythological beasts, and be integral to birds and bats and insects, and might be glorious or workaday or fluttery or super-aerodynamic, but empty? Not so much. But this pair of wings seems to have a life of its own, their sweep echoed in the snow-like pattern to either side, and they almost seem as if they might be donned, tried on by a wing-shopper for fit and sartorial effect, taken out for a run around the block to assess their loft and effulgency.

The image partakes of the myffic, because there aren’t really any wing haberdashers in our world. Looking at “empty wings” we are led to imagine that there might be, and imagine that angels might wish to rotate through a wardrobe of wings for different occasions, and that somehow a photograph has transported us thither. Or the viewer might say “humph, seaweed on the beach, just twice as much of it” and pass along to some other image.

I’m trying to pull together the vocabulary to think and talk about the effects and affects and applied aesthetics of photography—about how and why some photographs work in the sense of transfixing the viewer with an epiphany, and in the sense of spawning a feeling of unforgettability for the image. We all have our own catalogs of such images, and there’s not necessarily a lot of agreement among appreciators of photography about what truly belongs in the canon. It’s subjective and personal, and that’s basically a good thing, in the many-mansions sense.

One of the writers who has put systematic effort into exploring these matters of photographic essence is Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida. I’ve read through the book several times, with each pass assimilating a bit more terminology and Barthian viewpoint, but it’s very French and demands a lot of a North American reader. I am no expert but…

Barthes does something very clever, while disclaiming any expertise (or, indeed, interest) in technical photography. He uses 25 photographs (many of them not familiar to most readers) to exemplify aspects he discourses upon. Who, for example, has ever given much thought to this image of Queen Victoria sitting on a horse?

(Queen Victoria, photographed by George Washington Wilson, 1863)

Barthes uses the image to introduce the idea that the photograph has a clear studium, an aboutness, something that it relates about its subject: it’s Queen Victoria, in the flesh (well, shrouded in a vast black dress) sitting on a horse. That’s what it’s a photograph of, its “historical interest” and identity in the wider world. But Barthes then points out that for him the photograph also has a punctum, an element that grabs the viewer and makes the image into something with a personal and memorable significance. Barthes’ punctum:

…beside her, attracting my eyes, a kilted groom holds the horse’s bridle: this is the punctum; for even if I do not know just what the social status of this Scotsman may be (servant? equerry?) [in fact he’s John Brown… and the horse’s name is Fyvie], I can see his function clearly: to supervise the horse’s behavior: what if the horse suddenly began to rear? (pg.57)

For me the unforgettable punctum of the photograph is John Brown’s sporran, that which marks him as a Scotsman in full folkloric costume. That’s where MY eye is drawn when I look at the image.

So here we have a couple of tools to help us talk about those effects and affects and applied aesthetics of photography to which I referred above. Barthes offers a number of others that I haven’t decoded yet myself, so another pass through Camera Lucida is on the docket.

And, going back to the “empty wings”, for me [and for sure Your Mileage May Vary] the image has a punctum in the homunculus that seems to form the point of attachment of this set of wings to our imaginary angel’s back:

As so often before, I wonder aloud if the wings and the homunculus were there before I unfolded the original image. Or did I create them? Or are they purely imaginary? When we read a photograph, are we just projecting a personal and idiosyncratic interpretation? Is a photograph a document whose significance is contestable, or maybe even fungible? Deep waters.