I was listening to a recent (July 14 2016) episode of Open Source as I walked yesterday, in which Greil Marcus was interviewed by Max Larkin about three songs (Dylan’s Ballad of Hollis Brown, Geeshie Wiley and LV Thomas’ Last Kind Words Blues, and Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground) that Marcus has written a book around (Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations). A short segment seemed especially relevant to issues of art and creativity that I’ve been thinking about lately, so I transcribed it when I got home:

To me, works of art, whether they’re songs, whether they’re novels, whether they’re paintings, whether they’re movies, are fictions: they’re imaginative constructs that people create and then they inhabit and then they tell you stories from that position, as if they’re true. But they’re making things up, they’re lying. These things didn’t happen. And so the fact that Geeshie Wiley and LV Thomas were from here as opposed to there, that they lived at this time as opposed to that time, all of that is interesting and will tell you something about how these songs came to be musically as part of a tradition, but will not tell you anything about why the recordings they made, and especially Motherless Child Blues and Last Kind Words Blues, are absolutely unique, why there is nothing like them. That is because they had the tools and they had the will and the desire and the genius to be able to turn that into an artifact that we can listen to and say “who ARE these people?” and when we say “who are these people, we don’t mean “are they really from Houston?” which is where they were from, was LV Thomas really a lesbian, which she was was. That’s not what we mean by “who are these people?”. It’s like, “what is this ABOUT?” How can people DO these kinds of things? It’s our sense of awe in the face of great art. It’s a sense of coming to grips with our lack of understanding of how something so beautiful, so preordained, so unlikely, has come to be.

click to hear:

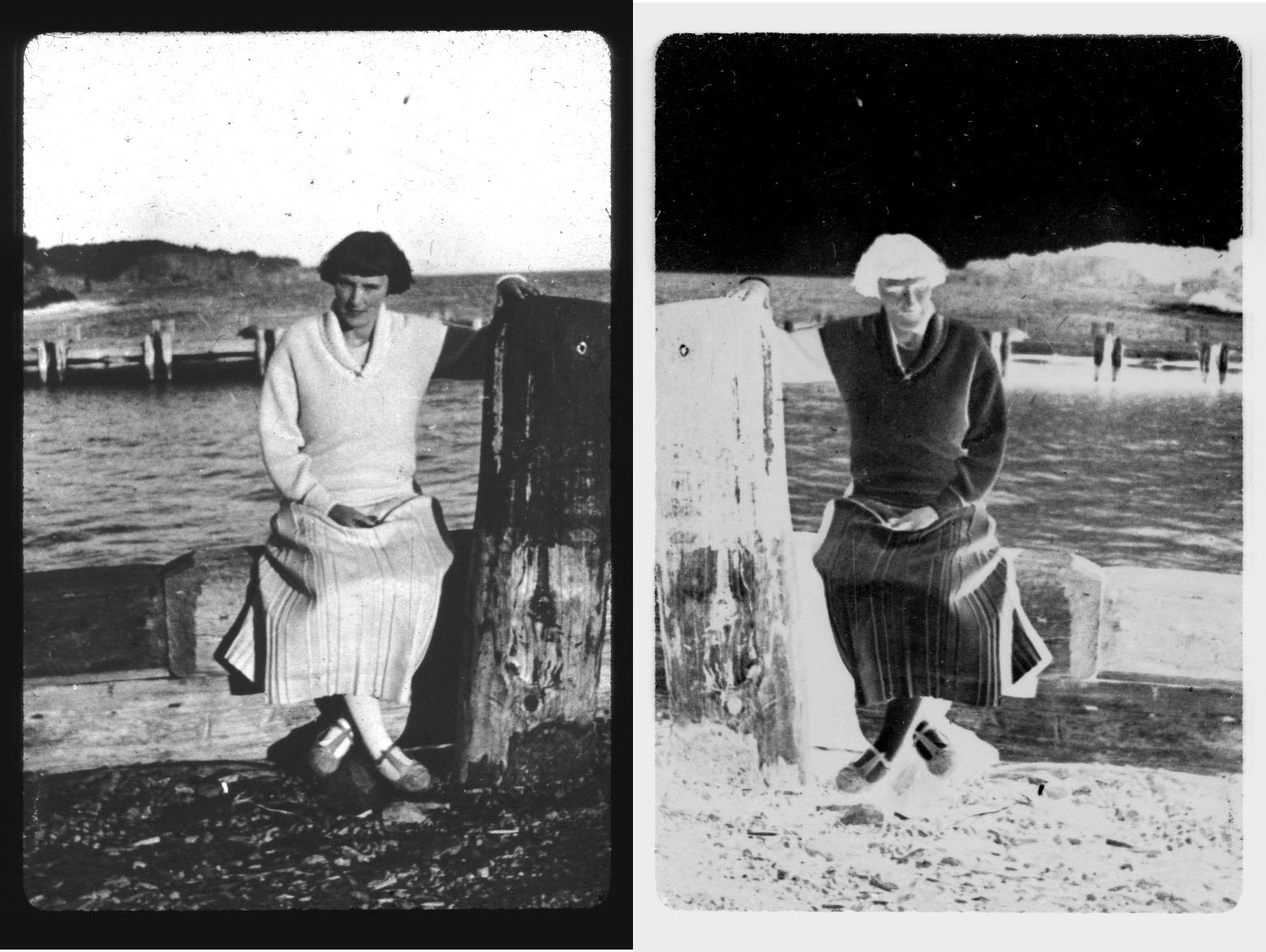

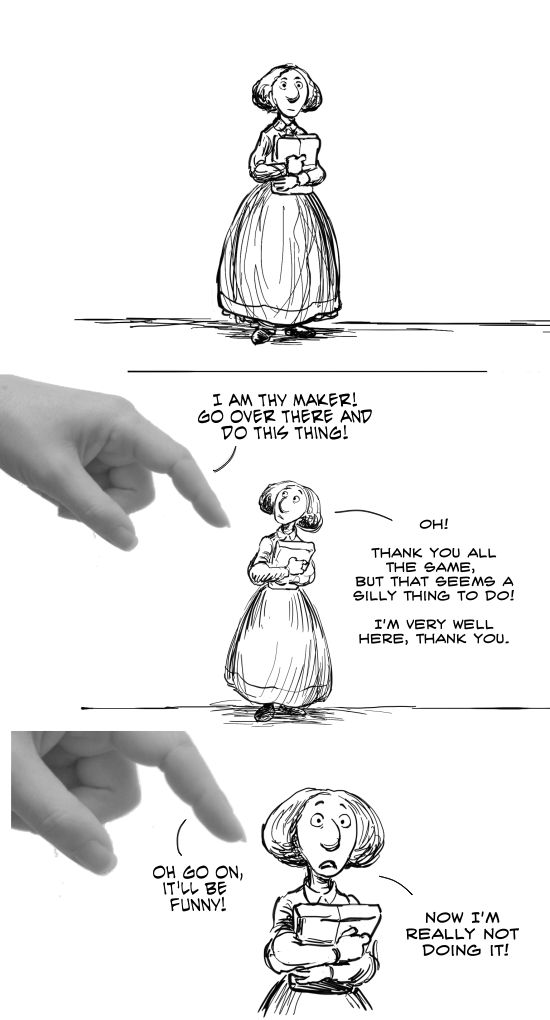

The sense of the sublime that inhabits the art that moves us (musical, graphic, narrative, photographic, whatever) is hard to pin down or distill into words. We knows it when we sees it, and that sense of knowing may or may not be transitive: others may not feel or apprehend or catch or get it. I’m aware of this feeling with every batch of photographs I process and put into my Flickr photostream—there’s an ineffable something that inhabits some images, often because of some imaginative construct that I’ve put onto them in capturing or processing. Sometimes there’s a story, either manifest or lurking under the surface. Sometimes it’s just a portent, or an allusion that only comes into focus within a set of images. Here’s one that produced that sort of frisson, though I haven’t yet imagined the narrative into which it might fit: