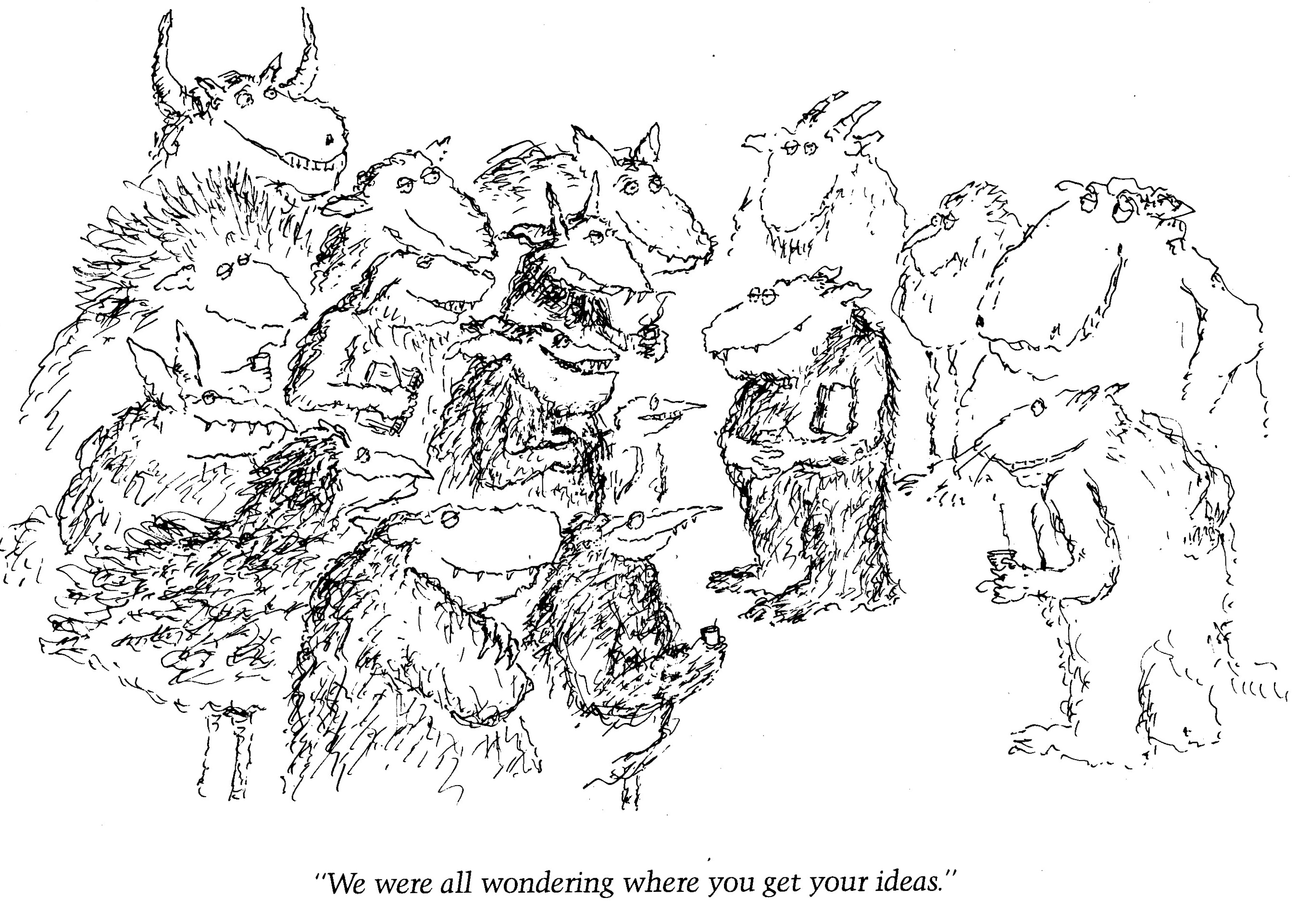

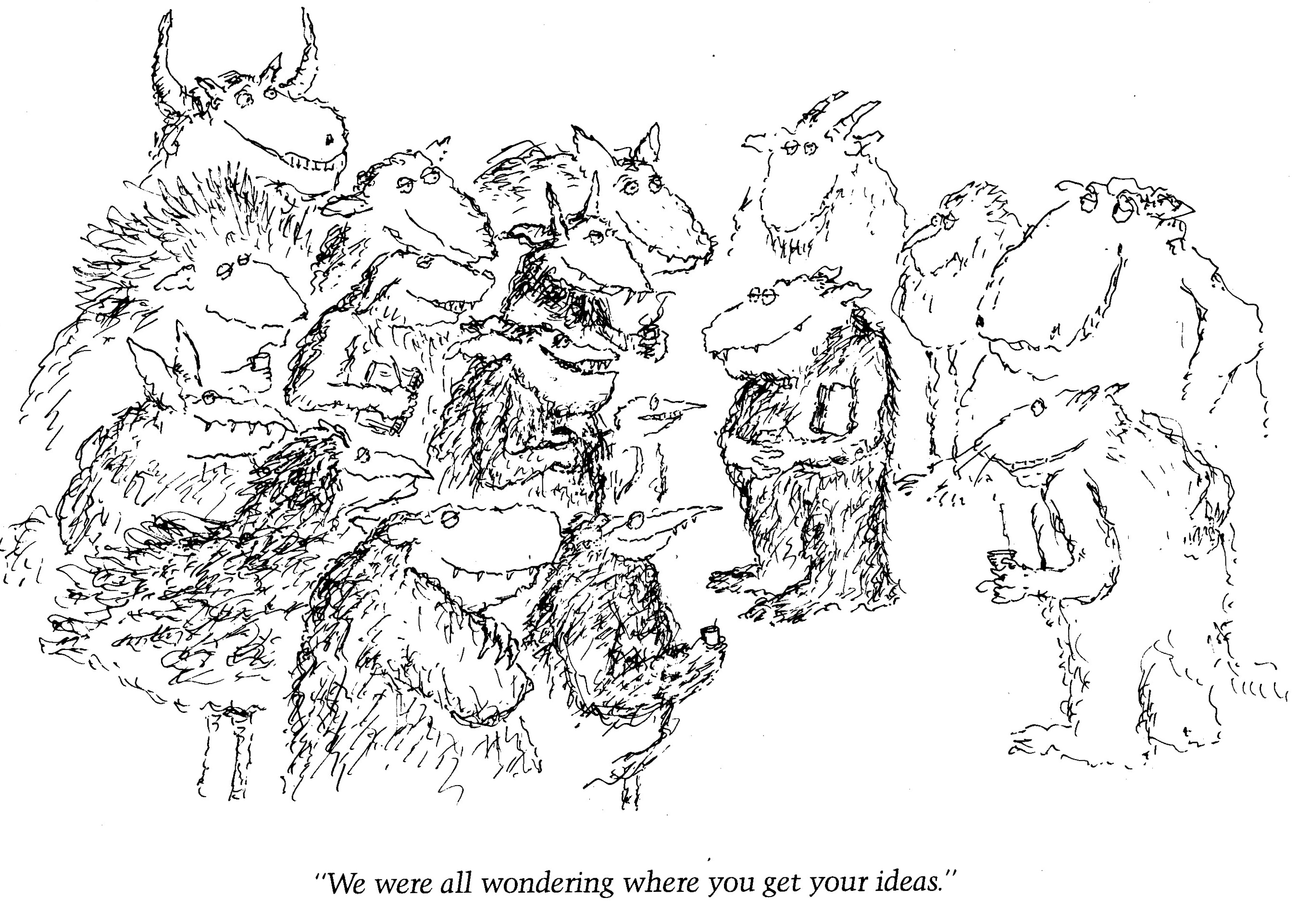

...Creativity is that marvelous capacity

to grasp mutually distinct realities

and draw a spark from their juxtaposition

(Max Ernst)

...Creativity is that marvelous capacity

to grasp mutually distinct realities

and draw a spark from their juxtaposition

(Max Ernst)

In 1958-9 I was in a Plane and Solid Geometry smart-kids class, the instructor of which was Phil Coyle, a recent Dartmouth graduate. He assigned us an expository paper/project. One person did topology, another explored graphing coordinates... and I chose to explore creativity. What was I thinking? The choice was certainly inspired by Brewster Ghiselin's The Creative Process (1952), which I had bought in a bookstore in Berkeley (another long story). I don't remember what I made of what I read, or what form my submitted paper took, but I held on to Ghiselen 1952 right down to now.

And picked it up again, admired the breadth of authors of brief essays (Henri Poincaré ... Max Ernst ... DH Lawrence ...Coleridge ... Henry James ... Henry Miller ... Katherine Anne Porter ...), read bits passim., and gave a careful reading to Brewster Ghiselin's Introduction. His style is a fascinating study in itself, very mid-20th c. academic-erudite, inimitable by any LLM I would think. Did I osmose anything from my first encounter? Now the words seem preternaturally wise...

Here are the bits I found especially eloquent:

...For the creative order, which is an extension of life, is not an elaboration of the established, but a movement beyond the established, or at least a reorganization of it and often of elements not included in it. The first need is therefore to transcend the old order. Before any new order can be defined, the absolute power of the established, the hold upon us of what we know and are, must be broken. New life comes always from outside our world, as we commonly conceive that world (4)...Stephen Spender's expression is exact: "a dim cloud of an idea which I feel must be condensed into a shower of words." Alfred North Whitehead speaks of "the state of imaginative muddled suspense which precedes successful inductive generalization," and there is much other testimony to the same effect. (4)

...More often it defines itself as no more than a sense of self-surrender to an inward necessity inherent in something larger than the ego and taking precedence over the established order. (5)

...The faithful formalist has no chance of creating anything. Hence a certain amount of eccentricity, some excess, taint, or "tykeishness" is often prized by creative minds as a guarantee of ability to move apart or aside, outside. Drugs or alcohol are sometimes used to produce abnormal states to the same end of disrupting the habitual set of mind, but they are of dubious value... (9)

...the desirable end is not the refreshment of escape into whatever novelty may chance to offer or impose itself, but the discovery of some novelty needed to augment or supplant the existing possessions of the mind. (9)

...The end to be reached, then, in any creative process, is not whatever solid or silly issue the ego or accident may decree, but some specific order urged upon the mind by something in its own vital condition of being and perception, yet nowhere in view. (10-11)

...it is likely that if Coleridge had only shut the door in the face of the man "from Porlock" who interrupted the composition of "Kubla Khan" he would have been able to continue the writing. But avoiding such fatal interruptions is a minor difficulty, scarcely illustrative of the problems of management. Conrad was able to leave the matter entirely to his wife. (11)

...only on the fringes of consciousness and in the deeper backgrounds into which they fade away is freedom attainable. (12)

...But in the unconscious psyche and on the fringes of consciousness, change is easier because there the compulsive and inhibiting effect of systems sustained by will and attention is decreased or ceases altogether. Though the system does not dissolve into nothing, it decreases in importance, becomes only an element in the unconscious psychic life, which might therefore be called the nonschematic in contrast to the conscious, which is dominated by system. The term "nonschematic" is suitable, further, for the unconscious and fringe activity, because much of it is so lacking in apparent organization that it seems altogether chaotic. (12-13)

...Subordination of everything to the whole impulse of life is easier for the innocent and ignorant because they are not so fully aware of the hazards of it or are less impressed by them, and they are not so powerfully possessed by convention. (14)

...The man who comes to depend on alcohol, or on paper of a specific size, or on some one favored environment in order to get his work done has narrowed his freedom of action and he may be resorting to automatic controls or to magic instead of relying on his skill, ingenuity, and sensitiveness. It is best to avoid idiosyncrasy and to cultivate the central disciplines. (16)

...Plan must come as a part of the organic development of a project, either before the details are determined, which is more convenient, or in the midst of their production, which is sometimes confusing. (17)

...To select a subject against inclination and force the mind to elaborate it is damaging and diminishing. (17)

...Every genuinely creative worker must attain in one way or another such full understanding of his medium and such skill, ingenuity, and flexibility in handling it that he can make fresh use of it to construct a device which, when used skillfully by others, will organize their experience in the way that his own experience was organized in the moment of expanded insight. (19)

...The secret developments that we call unconscious because they complete themselves without our knowledge and the other spontaneous activities that go forward without foresight yet in full consciousness are induced and focused by intense conscious effort spent upon the material to be developed or in the area to be illuminated. (19)

...Every new and good thing is liable to seem eccentric and perhaps dangerous at first glimpse, perhaps more than what is really eccentric, really irrelevant to life. And therefore we must always listen to the voice of eccentricity, within ourselves and in the world. The alien, the dangerous, like the negligible near thing, may seem irrelevant to purpose and yet be the call to our own fruitful development. This does not mean that we should surrender to whatever novelty is brought to attention. It does mean that we must practice to some extent an imaginative surrender to every novelty that has even the most tenuous credentials. Because life is larger than any of its expressions, it must do violence to the forms it has created. We must expect to live the orderly was we have invented continually conscious of the immanence of change. (21)

(full text of the book via Internet Archive)

Ghiselin's mention of The Man from Porlock inspired some digging into Coleridge:

The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1957)...For about forty years, from the time of his first walking tour in Wales in 1794 until within a few weeks of his death in July 1834, Coleridge wrote in notebooks. (xix)..."This line and the following are involved in an almost Lycophrontic tenebricosity", Coleridge once wrote in a letter. It must be admitted at once that if what was intended to be understood by a correspondent is not always clear, its Lycophrontic tenebricosity is limpid daylight compared with some of the "dark adyta" (to use Coleridge's own word for human inscrutability) of a notebook [adytum: the innermost sanctuary of an ancient Greek temple]. Nevertheless an accurate text has been regarded as the chief editorial obligation, and the text is therefore presented as nearly as possible as Coleridge wrote it (xxix-xxx)

...Annotations, emendations, and indexes, it need hardly be said, will never explain Coleridge; they are here offered by "a partial, prejudiced and ignorant historian" who wishes to suggest that a great deal of pleasure can still be had by anyone who participates in this endlessly rewarding game of hares and hounds in which the excitements of finding or scenting the trail through arduous country are not less because the chief quarry will always get away.

Editing Coleridge's Marginalia George Whalley elaborates

Maria Popova: