The Science Librarian's oversight of the Information work in each section would be a valuable addition, but the question is how the Science Librarian's contributions could be integrated, and what he/she will look at to exercise that oversight. The Web page element that was so central to Bio182 isn't really feasible in the several sections, since few Biology faculty are likely to see teaching those skills as a facet of their pedagogy. In any case, librarian participation in the Fall 2005 iteration is problematic: there will be no Science Librarian in the office.

Maryanne told me that she wants how-to units for

- PubMed

Strengths: extensive biomedical coverage, frequent updates, some links to full text [via Links ==> LinkOut], Related Articles, Review articles identified as subset, link to OMIM search --also protein and nucleotide databases

Very easy entrée, to a vast literature, via a Google-like search box. Links to full text for many journals.

Limitations: many obscure journals and highly specialized biomedical research - Web of Science --see screencast

Strengths: Cited Reference searching, ability to limit to Reviews, wide-ranging coverage, frequent updates, citation alerts, Cited References button, Related Records button

Limitations: 1990-2005 coverage, only most-cited journals, limited links to full text (we have access to many more) - Cambridge Scientific Abstracts [Illumina]

Strengths: multiple databases, tabs for conferences, Web sites, "peer-reviewed journals", limit to PT=review, Full Text button for some (not all) of our holdings

Limitations: WebBridge buttons for all, not just our holdings, are displayed ...confusing to students(may be fixed soon) - Basic BIOSIS [though I wonder why...]

Strengths: indicates Leyburn Library for holdings (WebBridge button, holdings summary under "See more details for locating this item")

Limitations: limited to 350+ "core" journals, indirect linkage to full text

- Google Scholar

Strengths: familiar interface, 'Cited by' in results (default order), links to full text for many

Limitations: not all links to full text are correct [doesn't know that we have Virology 1999, formerly Academic Press and now Elsevier]; and unclear just what sources are included/excluded (it is after all a beta product) - HighWire

Strengths: "the largest repository of free full-text life science articles in the world, with more than 850,000 free, full-text articles online", about 25% of titles have some or all full text free, Citation Map feature

Limitations: limited to 850+ titles - OMIM

Strengths: essential source for genetically-linked diseases

Limitations: - BioOne

Strengths: non-profit aggregator of society publications, " full-texts of high-impact bioscience research journals",

Limitations: 90+ journals - ScienceDirect

Strengths: 7 million articles

Limitations: Elsevier journals only, many accessible only via ILL or "$Order document" at about $25 - Scirus

Strengths: journal/Web results, suggests refining terms, links to PubMed Central full text [e.g., PNAS], sort by Relevance or Date

Limitations: "Full text available from ScienceDirect generally leads to "$Order Document" - We may have SCOPUS in the Fall, but I can't get to it now.

Some of the above are especially useful in certain circumstances (e.g., when you NEED the full text of a primary or secondary article...)

It's really worth asking what it is we want students to be able to do, in the broadest sense. My answer: they should be able to engage with the literature[s] of Biology, and have a clear idea of where to look, and what to do with what they find. Primary and Secondary literatures are part of the shorthand I've used to introduce them to practical methods in the textual and documentary side of research.

I recently ran across an interesting version of the research process, well worth repurposing to fit the circumstances of a searcher in a scientific field (though it's cast in Venture Capital terms), from Tim Oren's The Art of the Fast Take (emphasis added):

...every technology and market has a private language. It's built of terms of art, but also names of landmarks such as products, famous papers and projects, labs, and researchers and other experts. To begin to understand the market you need to learn this language. Fortunately, such a distinctive use of language and interlinkage of people and information artifacts is the very best thing you can have to feed Google or other modern search tools.The posting is about a page and a half, really worth the time to read and cast to fit one's own purposes. A few more bits:

You are looking for reviews or survey articles, as recent as possible. Skim them. Make sure these guy's idea isn't obviously misfit or already common knowledge. But you're mostly looking for more names, particularly of analysts, technologists or researchers who are commonly quoted... You're looking for competitive analysis, and also for corporate white papers. The latter will be 'spun', of course. What you're trying to extract are the key competitive issues, current and envisioned, and the code phrases used by the various competitors to tout their advantages and diss the opposition. You may strike out on the analysts if it really is a nascent area... With luck, you'll know someone on the list, or have a mutual friend. Buy a couple of lunches... Somewhere, there is a good argument going on in this field. Go find it. It may be on blogs, mailing lists, or at conferences, but it's likely to have an online presence and perhaps an archive. Read as much as you can handle, taking careful note of people and company names... Get a big piece of paper, your various lists of terms, people, products, etc., and make a network graph, cluster chart, or whatever works for you, noting central issues and people. You're not an expert, but you've now got some of the fundamentals of the technology and the market structure laid out.OK, so scholarly research isn't business, still less VC activity, but there's a lot here that's just exactly what we'd like our students to internalize as they start to figure out a field or a research area.

A central point here: linguistic problems lie at the heart of any inquiry. Collecting and exploring terminology, and mapping the interrelations of concepts, is an essential step and might as well be made explicit.

Another: interlinkage is really worth exploring, whether it's viewed in terms of researchers, articles, subdisciplines... Who has been influenced by whom? Where have people studied and done postdocs? With whom have they published?

And 'arguments' aren't always disputes: sometimes they may reflect different ways of mapping/visualizing/parsing the same reality, or different evaluations of salience.

This list of Biology journals was compiled for the 2002 serials review and is still pretty much accurate (a few have been added since the list was last tended, and it's no longer being updated). The titles are linked to their Annie records, and thence to electronic access, where available. The list also includes serials that lead to the Review literature, which I've considered really important for students to encounter.

So the question for me is: what can I leave that would be a truly useful legacy? Maryanne says "Wisdom of Dr. Blackmer", but I'm not sure how to define that commodity, or how to break it into the most digestible/useful components. Webpages and screencasts are surely the appropriate media, but even the best of those need context to make them comprehensible.

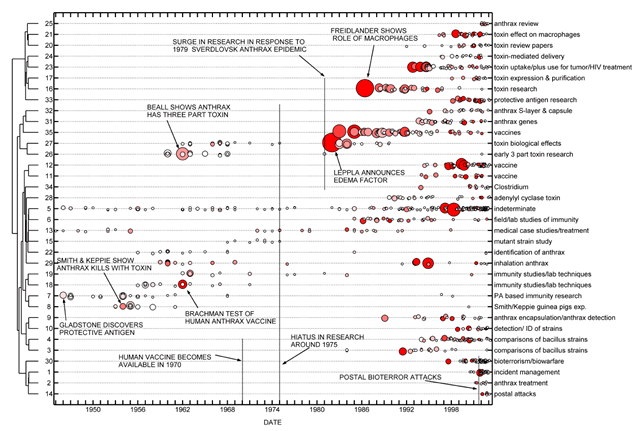

I happened upon a very nice example of visualization of a literature:

...see more details ...and see the PNAS SupplementMapping Knowledge Domains (2004) for much more!