(snagged from http://www.dlib.org/dlib/june02/shabajee/06shabajee.html)

(from a google image search)

I want to disclaim expertise in these areas, and claim instead the honorable mantle of a student of emergent technologies generally, and digital information systems in particular. I continue to discover and read and try to absorb the implications of a wide range of materials, and I'm perpetually at or beyond the edges of my own safety/comfort zones. In two weeks or two months I'll probably see many of the issues differently...

Building a digital library for Web distribution is potentially hazardous to your institution, and not just because there may be questions about ownership rights for items. Any materials you put onto the Web are there to be found and repurposed by anybody who finds them. The term "mashup" may be new to you, but more than 12,000 Web pages mention the word (see mashmix.com FAQ for one take) and the remix culture is remarkably active in the blogosphere. I think it originated in a UK music scene of the 1990s, which figures in King Rat, a novel by China Miéville... but that's a digression. See Wired "atlas of the intellectual property world" for an interesting graphic treatment. For more education in new media, take a look at Peter Halley's WebTake on Paul Miller's Rhythm Science, and the Supplement to M. Katherine Hayles' Writing Machines ...and Eric Loyer's WebTake on Hayles' book... my mind is still reeling.

Point is, digital information is really different from the analog print and image formats we all grew up with. Some of the metaphors and definitions from the paper-based libraries of our youth simply don't fit very well with the emerging realities of digital libraries, and it's we who have to change, especially if we're aiming to build effective digital collections. We have to learn a new vocabulary ('repurposing' is just the beginning) and cope with the implications of technologies that are a struggle to understand.

The extremes in the realms of copyright are clear enough: the RIAA, MPAA and other "industry" organizations are busily suing "pirates" who swap music files and download bootlegged video, and ownership in the world of publishing has become more and more concentrated in a few [greedy] hands... but on the other hand, some authors are releasing material onto the Web under Creative Commons licenses, and U.S. government publications are explicitly in the public domain and not copyrighted (see Information About Reprinting U.S. Government Publications from the GPO) --one sometimes encounters the term copyleft (cf Wikipedia article, and consider also Copyfight, a blog about "the nexus of legal rulings, Capital Hill policy-making, technical standards development and technological innovation..."). In between lies a very complicated landscape of law and custom and legal activities, and libraries (and educational institutions) inhabit a special zone.

(If you are interested in copyright as a battle line in the Culture Wars, I know of no better current example of the power of the blog medium than Cory Doctorow's June 17th 2004 talk to Microsoft's Research Group on Digital Rights Management (DRM) --a beautifully written piece, worth attending to for how the message is conveyed as well as for its content. See also an annotated version, or listen to an audio version. Three days later, more than 9000 Google links...)

All of us are far more interested in the practical details than in the philosophical or legal niceties. What can we do? What must we do? What mustn't we (or those under our tutelage) do? How should we protect ourselves (and our institutions) against the unknown? There are some rules of thumb, and some procedures. I draw heavily on Mary Minow's presentation at School for Scanning, summarized in her PowerPoint slides (from http://www.librarylaw.com/SFS.ppt where they will be until 30 July). The basic steps to go through as one contemplates a digitizing project:

Is the material in Public Domain? (if so, digitize at will)Also useful:

If not Public Domain, can it fit under the archival in-house terms of Sec 108? (digitize if comfortable with limitations)

If not Sec 108, under Fair Use? (digitize in good faith)

If not under Fair Use, seek permission... but recognize that it's often DIFFICULT to locate rights holders --see How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work from Library of Congress --and also note U. S. copyright renewal records search (Michael Lesk)"Any book published during the years 1923-1963 which is found in this file is still under copyright, as are all books published after 1964 (although until 1989 they still had to have proper notice and registration). Books published before 1923, or before Jan. 1, 1964 and not renewed, are out of copyright. This file does not contain listings for music, movies, or periodicals."

AuthType Basic

AuthName "Limit by IP or Domain"

satisfy any

order deny,allow

deny from all

allow from 137.113. .wlu.edu

17 U.S.C. 108(h), essentially permits a nonprofit library, educational institution or archive to reproduce or distribute copies of a work, including in digital format, and to display or perform a work during the last twenty years of the copyright term as long as that work is not commercially available.

The Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania is holding a conference this weekend on the growing copyright problems facing scholars using digital media. "Knowledge Held Hostage: Scholarly Versus Corporate Rights in the Digital Age" examines the overlap of creative use of technology with (often inadvertent) copyright infringement.(links well worth exploring...)

Collections consist of items, and the most basic task (once 'item' is defined --sometimes a non-trivial hurdle) is organizing them: sorting into categories, naming the sets and subsets. The basic reason to do this: you want to enhance access --to make it EASY for your users to find what they're seeking, and grouping like things together is a good basic strategy.

A good general background resource on classification is Bowker and Star 2002 Sorting Things Out: Classification and its consequences

my extracts include a lot of the essential general points. The book provides extended examples from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC).

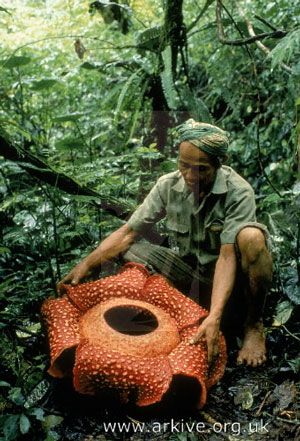

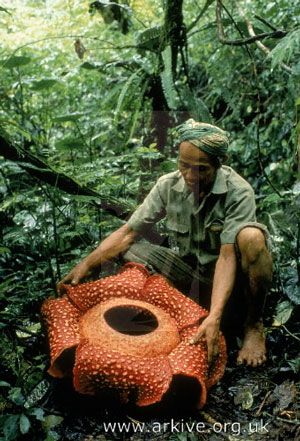

Here's a nice example of a Problem: the items here are some images of ...xxx...

In this case the items are separate images, jpg or gif files. We can say pretty clearly what these images are about (Rafflesia spp, the largest flower in the world, found in Malaya, Sumatra, and Borneo), but handling them as a collection of images presents some problems. How are they likely to be retrieved? What needs to come with them (explanatory text, pointers to related resources, attribution, geographical coordinates...?), and [therefore] what data should be associated with each? Are they part of larger collections, so that their records need to conform to an established format? It's much easier to build a usable collection if those questions are addressed at the outset.

Another example: I have an enormous collection of recorded music, in vinyl, CDs, cassette tapes, and now some MP3s. If I wanted to build a digital library to house records about my records, how should I set about it? Is the item a single disk or tape... or is it a cut/track that can be named and located as a subpart of the single disk or tape? The decision has dire implications for the scope of the data entry task AND the usability of the resulting database/library. If I want to retrieve the many versions of a single song, or the songs on which a particular musician plays, I need to have made the 'item' decision at the level of the cut/track, and not the disk/tape. (For this example, consider the possibilities implied by the existence of musicbrainz.org --see also TunePimp Library, and recognize that many domains have similarly useful utilities)

For any collection, it's a good idea to think through these questions before going on to the question of how to organize and classify the component items:(this is a good moment for a hands-on exercise, to discover where the problems may lie with specific collections and projects)

- what are the ITEMS in your collections?

- Are there different types of items that have different characteristics?

- What are the elements of each type of item?

- What elements are mandatory/optional?

- Will items have pedagogical notes? Annotations?

- Will items be developed by your team, or accessed from other locations?

- Will you need to track multiple exemplars, i.e, masters and copies for use?

- How will inclusion in your library add value to items?

Increased access through more users?

More detailed access (for example full-text search)?

New use through associations not possible before?- What subsidiary information will be tied to items?

- How do copyright laws pertain to your items?

Once the requirements and intentions are clearly established, the organizational tasks can begin. In most cases, we work primarily with words: our problems are to a considerable degree lexical and syntactical. Indexes are a basic way of taming the lexical, by creating and populating categories.

There are indexing methods with various degrees of constraint:

For some domains the choices of terminology seem pretty clear, because existing thesauri, controlled vocabularies, and ontologies may be appropriate sources for standardized and consistent (and authoritative) sets of terms appropriate to items and collections. See

A-Z of Thesauri from the High Level Thesaurus ProjectThe overwhelming advice, quoted and requoted, is to use an existing controlled vocabulary if at all possible. When no single controlled vocabulary seems appropriate, it's necessary to construct a pragmatic terminological/organizational system that can handle the variety to be classified. If nobody but the creator ever uses the classification, it can be idiosyncratic... thus, I can [usually] find the books and records in my own collections, but nobody else can. If a collection is ever to be used by others, it may eventually become necessary to transform an ad hoc and personal classification into a standardized one. Some would argue that one should begin with an orderly system... but that's a matter of personal style.

and

Taxonomy Warehouse

and

Traugott Koch's Controlled vocabularies, thesauri and classification systems

for some examples (alas, some links don't work...).

See also

'Selected Schemes' on Candy Schwartz's "Subject Analysis - Vocabularies" page

(the obvious exercise: explore the linked resources to find possibly-relevant controlled vocabularies... and articulate why they aren't sufficient)

If one needs to consider building a classification system, or adapting an existing system to one's own materials, some of these resources from the Web may be helpful:

What is a Controlled Vocabulary, and how is it useful? (basics, primarily for image collections --but links are worth following)Arguably the quintessential book on building thesauri: Thesaurus Construction and Use: A Practical Manual (Aitchison, Gilchrist and Bawden) Europa 2000 --but Anderson and Nicholls quote Aitchison's advice: "whenever possible, 'adopt in toto, with minimal alteration' an existing thesaurus"Flow of work in thesaurus construction (diagram)

Keywording systems fall into either one of two styles.Most commonly used, although not always the best, is the open vocabulary. If you look at an image and use whatever words it inspires for the keywords, you're using an open vocabulary. One day you may keyword an image as Ship, Harbor. Entered on another day, you might have keyworded the very same image as Boat, Port. Another time you might use Watercraft and Harbour.

When searching for this sort of image, who knows what youíll find or overlook because of inconsistencies in an open vocabulary. Of course, you can look for all entries that contain Harbor or Port or Anchorage or Boat or Ship or Vessel, but itís hit or miss proposition that requires a vast patience or a good memory. If you find no entry for Boat, you must keep looking, trying other words in your keywords. When you discover Ship, you move on, never discovering all the others that got listed as Watercraft.

In a controlled vocabulary your keywords are limited to a specific set of words. Ideally this list of words is printed in an index or available on a computer for your reference as you apply keywords to images.

Converting a controlled vocabulary into an ontology: the case of GEM [Gateway to Educational Materials] (Jian Qin & Stephen Paling)

The Role and Use of Controlled Vocabulary in Increasing the Sharing and Use of Ecological Data Information International (PowerPoint presentation, 1998 conference)

===

here's the sort of problem we face:

Suppose a multimedia producer used still images in an animation project. Let's say he or she pastes elements--a clock, a castle, or clouds--from photos into certain frames. Who holds the copyright to the final product? Most experts agree that the original copyright holder and the multimedia producer share the rights. No one seems sure how to handle the sharing in practice.

(http://www.timestream.com/stuff/neatstuff/license.html --1994)