...Douglas ak Naong Rh. Naong Jumbit, Melugu Scheme,...Telah dibantu dengan projek ternakan ikan keli dalam tangki PVC di bawah program 1AZAM pada tahun 2010. Input seperti tangki PVC, jaring, benih ikan dan makanan ikan diberi pada bulan April 2011.

Selepas ikan mencapai berat badan kurang lebih 200 gm setiap ekor selepas 4 bulan, ikan itu kemudian dipindahkan ke dalam sistem ternakan sangkar di dalam kolam berdekatan untuk dipelihara selama 2 minggu supaya menghilangkan bau. Ikan keli yang masih hidup dijual pada harga RM8.00 sekilo.

Beliau juga memproses ikan keli salai yang sangat popular di kalangan penduduk tempatan. Ia dijual pada harga RM10 sebungkus seberat 500 gm. Isterinya yang menolong menjual ikan keli salai di pasar Lachau. Beliau juga ada buka sebuah gerai depan rumahnya untuk menjual ikan hidup dan ikan salai.

Sebelum bantuan, pendapatan beliau sebagai seorang petani adalah RM250 sebulan. Kini dengan bantuan 1AZAM, purata pendapatan daripada menjual ikan sahaja adalah RM500-600 sebulan.

PROJEK TANAMAN SAYUR-SAYURAN

Resat ak Gaek Rh. Chek, Melugu Scheme

Those settlement schemes Borneo Post online 8i17

...In Malaya, rural areas were being developed for the poor Malays; in Sarawak, one way of reducing poverty especially among the rural people was the development of their land for agriculture....In the early years of Malaysia, Sarawak began to get organised in terms of land development. There were seven schemes sited in all the five Divisions of the State.

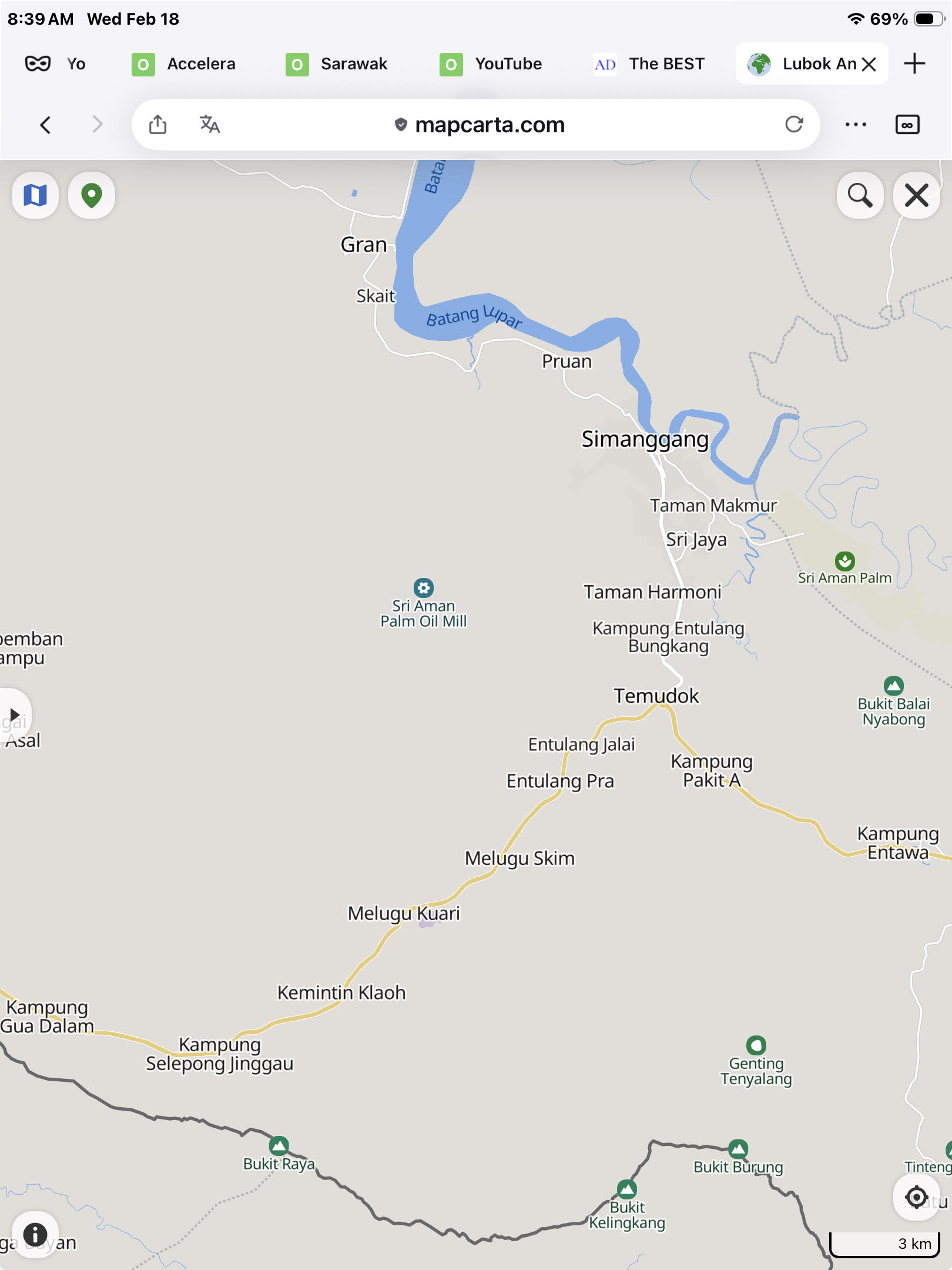

For instance, Triboh in the First Division, Melugu and Skrang in the Second Division, Maradong and Sebintek in the Third Division, Lambir in the Fifth Division and Lubai Tengah in the Fifth Division.

All of these projects were funded by the state government; they were earmarked for people without land, especially the Chinese farmers and for the Natives to learn how to become sedentary farmers instead of being shifting cultivators year in, year out.

...Melugu

Most of the settlers were landless people from around the area in the Simanggang District but priority for settlement was given to the people who had surrendered their NCR land for the development of the scheme.

All expenses connected with the infrastructure were borne by the government through the Sarawak Development Finance Corporation.

Each family was obliged to pay for the house built for them and upon the full settlement of housing loan, they would get a Mixed Zone title for the land together with their other property (rubber garden) which might be a distance away from the house.

Skrang

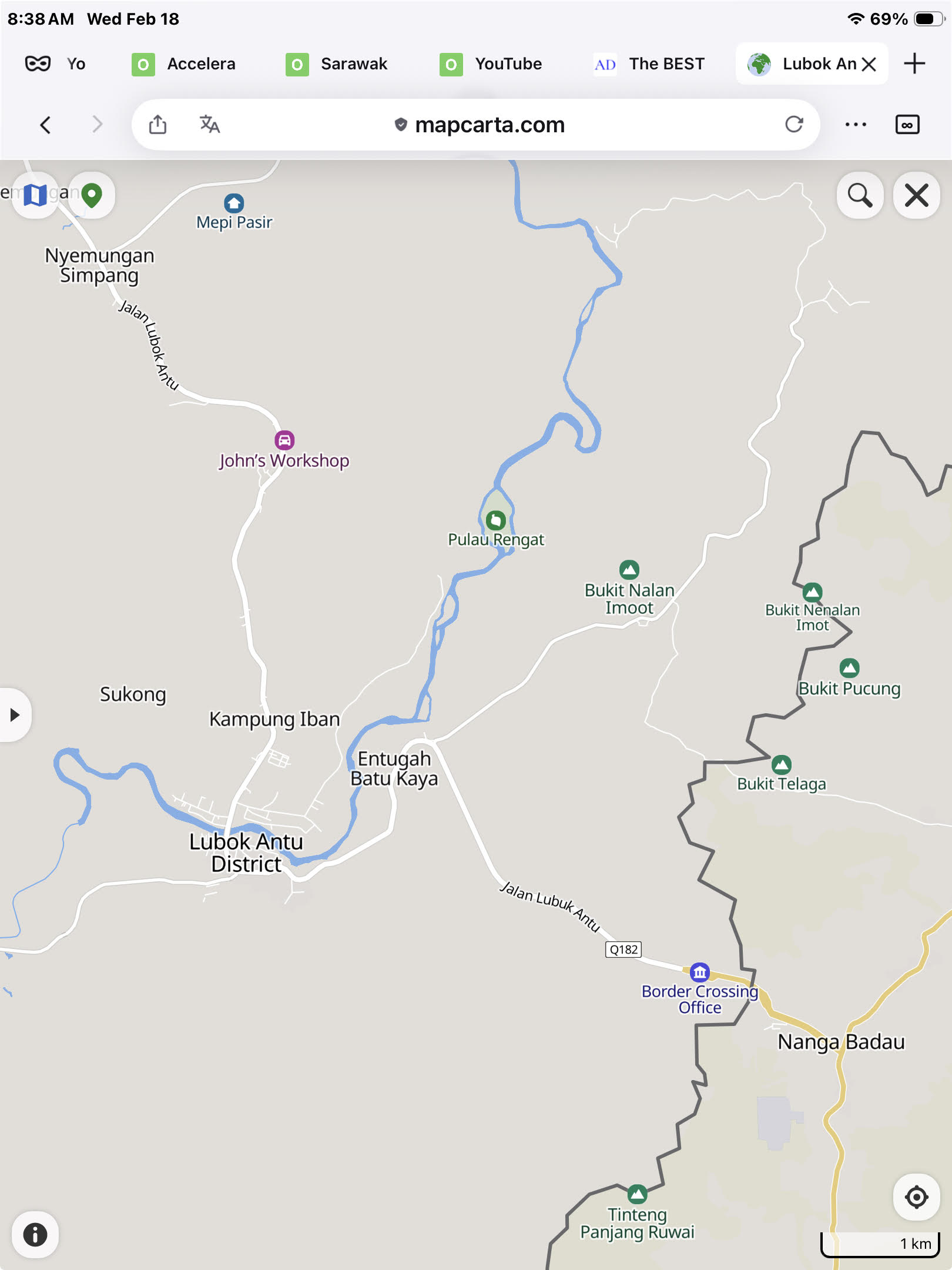

This scheme was specially created for the settlement of people near the Indonesian border. They had been subjected to harassment by the communists; the government was concerned that the Iban might join the commies who were bent on pulling down the government of the day.

The same concept of development for Melugu was applied to Skrang except that the land for the latter scheme (Skarang) was surrendered or given by the locals to the government for the benefit of the people from Lubok Antu under Penghulu Upok.

...After so many years of the existence of these rubber schemes, I am wondering if any of them can be called a success story.

No one can really say they are a success or failure by watching from the roadside in a passing vehicle.

Are there any more rubber trees left in those rubber schemes? Are the houses still standing or new houses built in their places? How many house lots and rubber lots have been purchased by outsiders?

It's high time the government undertook the study of each and every scheme that I mention above to see if they have served the purpose for which they were intended —s to give land to the landless; how many Natives have really practised sedentary farming; what were the problems encountered by the settlers as a result of the mistake made by the planners or the implementers/mangers of the projects?

Contradictions in land development schemes: the case of joint ventures in Sarawak, Malaysia Dimbab Ngidd Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 43, No. 2, August 2002

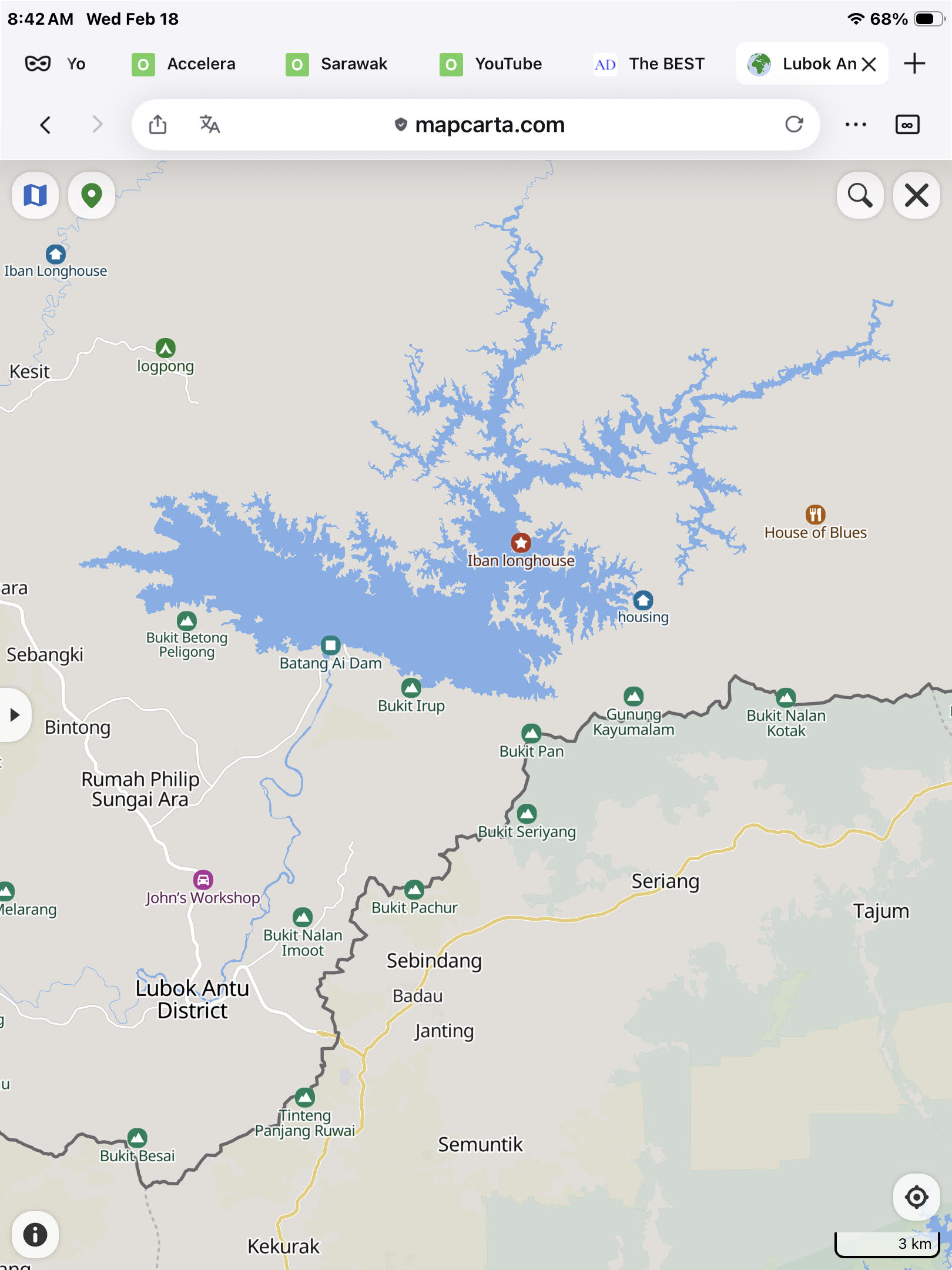

...The rubber-based resettlement schemes were a failure due to falling rubber prices in the 1960s, and also because the schemes failed to guarantee employ- ment security to settlers (Salleh, 1986). Many settlers simply left the schemes for more lucrative jobs in the logging and construction industries. Managing the rubber schemes was also problematic because many settlers chose to sell their rubber sheets to middlemen instead of to SLDB as a way of to evading loan repayment. Breaching of agreements over the standard field maintenance was also commonplace and this caused many rubber lots to be neglected and/or abandoned. In 1982 the government decided to abandon all these rubber schemes, and left the settlers to look after their own welfare....In 1982, a hydropower-based resettlement scheme was established at Batang Ai, Sri Aman Division. The resettlement scheme was necessitated by the construction of the hydro-electric power dam project across Wong Irup in Batang Ai, which created a reservoir of 8,650 hectares. Despite strong resist- ance to the resettlement scheme, the government went ahead with the relocation exercise (King and Jawan, 1992). This caused the displacement of 25 Iban longhouse communities with a population of 3,600 individuals. A total of 1,595 families were resettled at the land scheme. Each family was given 4.5 hectares of farmland, 1.6 hectares less than originally proposed (Cramb, 1979, Ngidang, 1991). The farmland consisted of 2 hectares of rubber, 1.2 hectares of cocoa and 0.4 hectare for a garden plot. Another 0.8 hectare of rice land, has yet be given to the settlers as promised. As in the two previous land resettlement schemes, settlers in the Batang Ai scheme were mainly hired as labourers in the cocoa and rubber plantations managed by the Sarawak Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (SALCRA). When cocoa prices plunged in the 1980s, cocoa was abandoned.

...Relocating Iban populations to new environments ‘forced' them to adopt mono-cropping farm schemes, and prevented them from diversifying their agro-economic activities. Unlike in their former long- houses, their employment security was not guaranteed in the schemes because they did not have access to and control over land resources. No doubt the schemes provided cash incomes, but in the absence of land for growing food crops to meet household subsistence requirements people have had to buy food using the limited income derived from the schemes. When prices of agricultural commodities such rubber, pepper and cocoa plunged, the effect was disastrous on the settlers. They had nothing to fall back on that could cushion such an effect. The problem was compounded by poor management and organisation, the unwillingness of settlers to adhere to the disciplined lifestyle required by the standard practice of plantation management (Salleh, 1986), low productivity, high labour turnover and shortage of labour (King, 1992: 82).

...In contrast to the resettlement schemes run by SLDB, SALCRA's in situ con- cept of land development was designed to bring development to the door of Iban longhouse communities themselves instead of relocating them to entirely new and different environments. SALCRA started its first oil-palm project at Merindun, Lemanak, in the Lubok Antu district, a poor area which had first been inhabited by Iban shifting cultivators about 400 years ago when their pion- eering ancestors migrated from the upper Kepuas in Kalimantan to Sarawak. SALCRA's projects subsequently expanded to the Kalaka-Saribas districts, Pakit/Undop, Melugu and Jaong in the Sri Aman Division. Todate, out of 41,889 hectares of estates developed by SALCRA, 40,648 hectares are oil palm, 1,053 hectares are in rubber and 188 hectares are in tea. About 54 per cent of the total area planted is in Iban-dominated areas, while the remaining 46 per cent of the plantations are located in predominantly Bidayuh areas. A total of 6,412 Iban families are currently involved in the projects.

...Managing a workforce of Iban, who are known for their relatively carefree lifestyles, and moulding them into a regimented and discip- lined labour force for an oil palm plantation, has been a formidable task for SALCRA.

...From sociological and psychological viewpoints, those in situ land develop- ment schemes are better suited to the Iban way of life because people are not uprooted as they have been in resettlement schemes. Landowners do not experience the stress and shock of being moved from their original longhouses to unfamiliar locations away from relatives and friends. They can continue to grow their subsistence crops for household consumption and cultivate cash crops such as pepper and cocoa on the lands not being utilised by the planta- tions. This arrangement actually helps to speed the rate of commercialisation of agriculture among the Iban longhouse communities because native custom- ary lands which are not taken by the plantations are available for cash-crop diversification. The in situ arrangement therefore provides both an employ- ment safety-net and food security for affected communities. But there is an associated problem: landowners do not want to work in the schemes because of the low wages. And for those that do, with a greater percentage of their household income coming from other economic activities, income from the schemes contributes only marginally to their household income. SALCRA is no longer able to attract the younger generation to work in the farm schemes and as a result the existing Iban workers consist mostly of older people. In a further irony, it is this acute labour shortage which has lead SALCRA to hire foreign workers.

... The focus of attention has shifted from the develop- ment of the Iban rural communities to ensuring productivity and profits from a joint-venture private sector oil-palm projects using cheap labour from the longhouse. Several important questions arise from these contradictions. How does the joint-venture oil-palm project reconcile its social responsibility or obligation to the people whom it supposedly assists when the profit motive overrides social issues associated with the economic pursuit? How can the poor people retain and/or access land resources when such resources are under the control of the private sector?

...The joint-venture concept (JVC) of native customary land development, which is currently being implemented in Sarawak is conceived as a joint partner- ship between the private sector, landowners and government agencies. It is described as a marriage between capital, land, labour and expertise. The Iban longhouse communities provide the land and labour; the private sector pro- vides the capital and expertise, and the government agencies act as the trustees or play the role of managing agents for the join venture project.

...Why did the landowners agree to the joint venture arrangement with the private sector if the majority of them did not understand the joint venture concept? In answering this question it is important to stress that these pilot projects were initiated not by the longhouse communities, but were the result of the usual government top-down intervention decisions in development. However, what was more unusual in this particular decision-making process was that the decision to form a joint venture with the private investors was made by Iban political leaders themselves and that those community leaders were prepared to accept the proposal without question, regardless of whether such a decision may harm or benefit their communities. The reasons lie in the wider context. The decision-making through co-optation which characterised this process by-passed the normal institution of randau, the Iban version of a dialogue or open discussion, where a community-wide consensus is obtained from the members. Thus, the consent to allow the private sector to develop their lands was not necessarily based on a majority decision or community-wide con- sensus. Some community leaders grudgingly went along with the decision for fear of being labelled ‘anti' government. Similarly landowners appeared to demonstrate antagonistic co-operation towards the authorities because of the fear of losing their lands in the future.

...Communication between ‘friendly' longhouse communities and officials was apparently of a patron-client form. These officials, who played the role of a patron, selectively interacted with their clients along party lines, and excluded some community leaders and other members of the longhouse com- munities. For this reason, certain community leaders were relatively more informed than others. Also these officials have had very limited communica- tion or contact with other longhouse

...When ‘unfriendly' longhouse communities raised certain issues or pertinent features of JVC which they did not understand, these communities were often construed as ‘anti-development' or ‘anti govern- ment' by officials. But when ‘friendly' communities raised the same issues, these ideas would be appreciated and/or tolerated. While officials were able to tolerate the critics from ‘friendly' longhouse communities about the project, they tended to label the viewpoints of ‘others' as offensive, although both parties said the same thing. This caused ill feeling among certain community leaders and longhouse communitie

...The institution of randau, the Iban version of participatory dialogue and the decision-making mechanism in a longhouse, can play an important role in creating awareness of, and sanctioning or legitimatising the projects. In this case however it was relatively under-utilised; community leaders by-passed the norm of randau in their rush to implement the JV projects, and doing so failed to take into account the viewpoints of the majority of members of the longhouse communities. Informal and intra-community communications also broke down. This was exacerbated by the infrequent visits from MRLD and MA officials and the problem associated with selective preferential communication exhibited by community leaders themselves.

The communication problems that developed between officials and long- house communities were compounded by the low level of formal education of longhouse communities.

...Landowners were also anticipating social problems associated with the influx of outsiders into the project area and feared that these outsiders might deprive locals of jobs in the plantations. If left unchecked, this would lead to unhealthy social relations where outsiders could possibly ‘control' local com- munities. This occurs against a background of plantations in Sarawak not employing locals because of the low salaries. The policy has always been to provide employment for local people, but the cost of hiring outsiders is less, so plantation companies often end up hiring foreign workers as cheaper labour.7

The second main concern was over security of land tenure. Slightly more than one-third (37 per cent) of landowners we interviewed in Ulu Teru and Kanowit were worried about the implications of the memorandum of consent, which they had signed earlier but had very little knowledge of. Such a docu- ment, according to the managing agents' officials, records the official consent of the landowners to allow the government to earmark the area and declare the locality a development area, prior to the implementation of the joint-venture oil-palm plantations. Their fear of losing their lands was highlighted by the fact that they had not signed any agreement with the government and/or private investors. They were not convinced that their native customary lands would be handed back to them after the expiry of the 60-year lease and they were also concerned over what would happen to their lands if the joint-venture company went bust.

...Examining the concept and practices of the projects thoroughly, it is hard not to believe that they are designed – whether intentionally or unintentionally – to prevent the Dayak community from having too much power over land resources in Sarawak. When their land resources are put in the hands of a trustee and then leased to the project for 60 years, these ‘landlords' will automatically become minority shareholders in the project in favour of an economic elite. While it is true that the rural Iban are one of the stakeholders, they are also labourers on their own land.

SALCRA: ITS CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SARAWAK RURAL AREAS DAYANGKU NORASYIKIN AWANG TEJUDDIN and NWANESI PETER KARUBI Oil Palm Industry Economic Journal (2023) pdf

Melugu adalah sebuah kampung pada asalnya. Usaha kerajaan ketika itu adalah untuk membuka sebuah perladangan. Ketika itu penanaman komoditi utama ialah getah. Dari hanya sebuah perkampungan yang sunyi ia bertukar wajah menjadi sebuah estet getah. Dari semasa ke semasa ia terus menjadi medan pertumbuhan penduduk dengan penempatan rumah-rumah peneroka yang disediakan oleh pihak perladangan. Tiada sesiapa pun yang menyangka dari hanya sebuah kampung yang sunyi menjadi satria penyumbang ekonomi.Ledakan penduduk mempengaruhi kemudahan fizikal kampung Melugu dan sekitarnya. Kemudahan asas seperti sekolah menjadi salah satu agenda utama selain pembangunan. Sebuah sekolah rendah perlu dibina untuk menampung limpahan kanak-kanak yang sama-sama berhijrah dengan ibu bapa mereka yang ingin merebut peluang pekerjaan di ladang getah. Menyedari hakikat ini, sebuah sekolah rendahtelah dibina untuk keperluan pendidikan anak-anak peneroka di perladangan getah pada 07 September 1959 dan dinamakan Melugu Primary School. Sekolah tersebut telah dibina dan diurus oleh majlis daerah tempatan.

Fasa kedua sekolah ini telah berpindah ke lokasinya yang baru 17 km dari pekan Sri Aman (sedia ada ketika ini) dan telah ditubuhkan pada 01 Januari 1965 memandangkan lokasi yang lama sudah tidak sesuai lagi kedudukannya kerana terletak di tengah-tengah kampung. Sekolah ini juga menampung murid-murid yang datang dari sekitar kampung yang berdekatan. Lebih 80% penduduk tinggal di kawasan rumah panjang. Oleh kerana jarak sekolah ini agak jauh dari kampung-kampung maka sekolah ini menampung murid-murid yang bersekolah di sini sebagai murid asrama. Sekolah ini dapat menampung sejumlah 200 orang murid asrama lelaki dan perempuan dari tahun 1 hingga tahun 6. Sekolah ini terdiri dari tiga blok bilik darjah, sebuah blok pentadbiran, sebuah dewan makan, dua buah pra sekolah, sebuah makmal komputer, satu blok asrama lelaki dan satu blok asrama perempuan.

Lubok Antu District Wikipedia

A History of Sarawak under Its Two White Rajahs 1839-1908 by S. Baring-Gould et al. Gutenberg and full text

CHAPTER IV THE WHITE RAJA OF SARAWAK from 19thc Borneo: A study in diplomatic rivalty

pdfs from JSTOR

PLANNED VILLAGES AND LAND SETTLEMENT SCHEMES IN SARAWAK Y. L. Lee Ekistics (1969) pdf

Land Settlement Schemes and the Alleviation of Rural Poverty in Sarawak, East Malaysia: A Critical Commentary Victor T. King Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science (1986) pdf

The Last Swiddens of Sarawak, Malaysia Ole Mertz et al. Human Ecology (2013) pdf

Borneo through the Lens: A.C. Haddon's Photographic Collections, Sarawak 1898-99 Cosimo Chiarelli and Olivia Guntarik (2013) pdf

Hornbill Carvings of the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia William H Davenport RES (2000) pdf

Good Governance and Human Security in Malaysia: Sarawak's Hydroelectric Conundrum Brendan M Howe and Nurliana Kamaruddin Contemporary Southeast Asia (2016) pdf

Pirates, Squatters and Poachers: The Political Ecology of Dispossession of the Native Peoples of Sarawak Marcus Colchester Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters (1993) pdf

Lessons from the oil palm sector in East MalaysiaFadzilah Majid Cooke et al. IIED (2011) pdf

Ethnic Language Use and Ethnic Identity for Sarawak Indigenous Groups in Malaysia so-Hie Ting and Louis Rose Oceanic Linguistics (2014) pdf

Indigenous People, the State and Ethnogenesis: A Study of the Communal Associations Tan Chee-Beng Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (1997) pdf

RAJA JAMES BROOKE AND SARAWAK: AN ANOMALY IN THE 19TH CENTURY BRITISH COLONIAL SCENE Leigh R Wright (1972)

The Partition of Borneo Graham Irwin 19th century Borneo

The Pirate Controversy Graham Irwin 19th century Borneo

Contradictions in land development schemes: the case of joint ventures in Sarawak, Malaysia Dimbah Ngidang Asia Pacific Viewpoint (2002) pdf

Michael Dove via JSTOR

Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: Implications for Theories of Agricultural Evolution in Southeast Asia

Environmental Anthropology: Systemic Perspectives

The Agroecological Mythology of the Javanese and the Political Economy of Indonesia

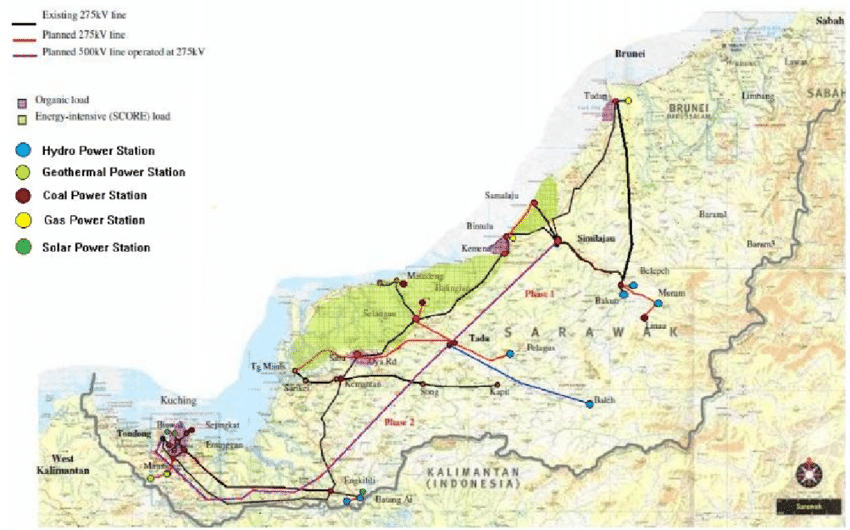

...the RM2.7 billion 500kV backbone to provide Sarawak with a second transmission grid. This massive state infrastructure was completed in 2017, stretching for over 500km from Similajau to Kuching Division. The second backbone has doubled capacity of the network and enhanced reliability particularly in the more densely populated southern region.

Project Gutenberg eBook of A History of Sarawak under Its Two White Rajahs 1839-1908

History of Sarawak Brooke Trust

19ii26

Hiding in the dark: Local ecological knowledge about slow loris in Sarawak sheds light on relationships between human populations and wild animals Priscillia Miard et al. Human Ecology (2017)

Rajahs and Rebels: The Ibans of Sarawak under Brooke Rule, 1841-1941 Robert Pringle

On and off the ethnic tourism map in Southeast Asia: The case of Iban longhouse tourism, Sarawak, Malaysia Sallie Yea Tourism Geographies

...This paper examines how some communities come to be 'put on' and 'taken off' the ethnic tourism map in Malaysian Borneo through a case study of two Iban longhouses in the state of Sarawak. The negotiations that occur when a potential destination is identified by a tour operator and those that occur when a community is threatened with the loss of destination status are important points to consider in this relationship since destination communities throughout Southeast Asia continue to 'slip off' the tourist map as outside agents deem them no longer traditional or exotic enough for touristic consumption. This threat to destination status can mean loss of a community's major source of income simply at the whim of tour operators.

Iban as a koine language in Sarawak Chong Shin Wacana (2021)

Culture Summary: Iban Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr. and John Beierle HRAF

Iban Mythology folklore.earth

Facing the Bulldozers: Iban Indigenous Resistance to the Timber Industry in Sarawak, Malaysia Matek Geram Human Rights Watch (2025)

...Malaysian logging company, Zedtee Sdn Bhd (Zedtee), a member of the timber giant Shin Yang Group.The Sarawak government granted Zedtee a lease to establish a timber plantation, Anap Belawit Management Area LPF 0039, that overlaps with the eastern half of Rumah Jeffery's territory. The operations require clearing the natural forest and replacing it with a tree farm. Zedtee also has a logging concession that overlaps with the western half of Rumah Jeffery, Anap Muput Forest Management Unit

POLITICS IN SARAWAK 1970-1976: THE IBAN PERSPECTIVE Peter Searle and Leo Moggie (review)

...The author tries to understand why the Ibans as the largest single ethnic group and signifi- cantly the largest bumiputera community in Sarawak failed to preserve its poltical power in 1963 and how the Ibans struggle to recapture the lost glory....Among the important factors put forward are historical antecedents of Brooke's policy of divide and rule. Tò the Brookes the Malays were fit to be administrators; the Chinese for commerce while the Ibans were only suitable to be warriors and 'noble savages'. The nature of Iban society adds further divisive elements. The author finds the Iban society is egalitarian and almost formless in terms of political institutions.

IN WHICH SENSE ARE THE IBAN INDIGENOUS? RE-IMAGINING INDIGENEITY IN THE CONTEXT OF DOUBLE-TIERED STATEHOOD MOTOMITSU UCHIBORI Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies (2020) pdf

Percentage population of Iban in Sarawak, 2020 Wikimedia Commons

Rural-Urban Migration of the Iban of Sarawak and Changes in Long-house Communities Soda Ryoji Geographical Review of Japan (2001) pdf

The Iban in Sarawak (1840-1920)Jürg Helbling

Violent Conflicts Within River Groupings

The Government of the Brooke Rajahs and their Strategies

The Suppression of Coastal Piracy

The Pacification of the Skrang and Saribas Iban