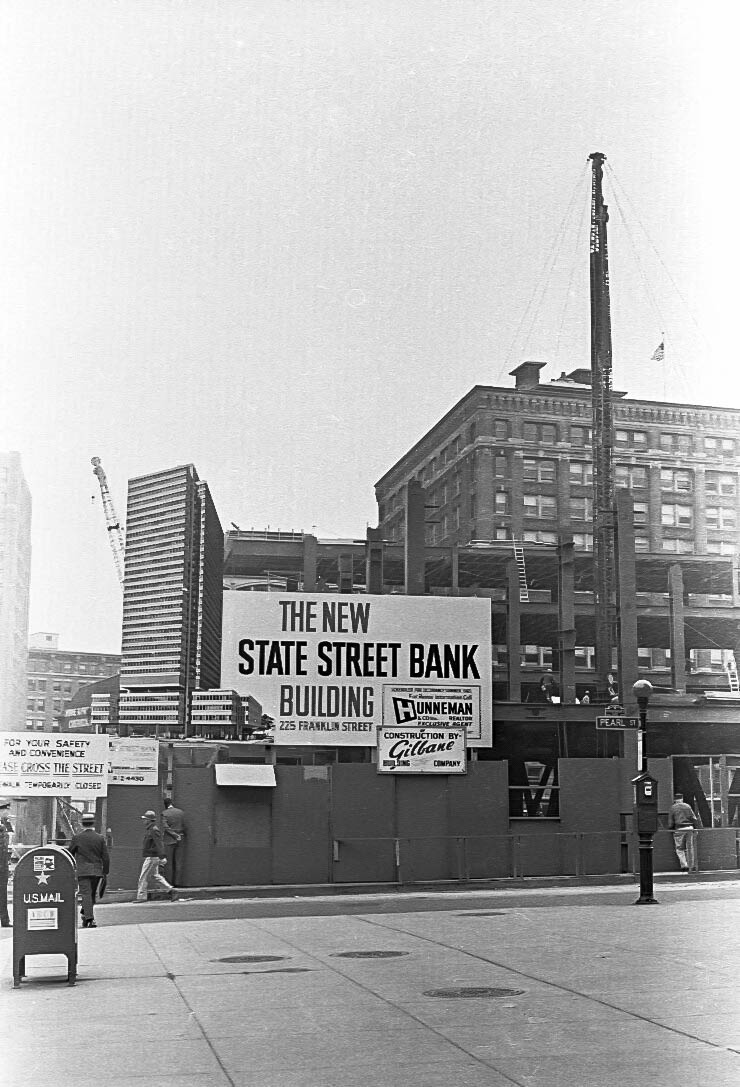

Where and how does a building begin? How should I approach the backstory of the State Street Bank building, in order to build the context for my first photos of its construction, which were taken in March 1964? The vital elements (or anyhow the ones I've thought of so far) include the decision to build, the financing, the site acquisition, the design, the choice of general and specialist contractors, the zoning changes and permitting, the overall plan of the project, site preparation (demolition, excavation), organizing the supply chain of materials and the scheduling of their delivery, the management of the site itself (security, safety, police, traffic, etc.). Each of those involved a great many organizational steps and decisions, long before any activity began on the site itself. I'm not sure how much of that complexity could be reconstructed more than 50 years later, or where to look. I did find commentary by the building's chief architect, and some later descriptive material as well:

see further detail from Heroic: Boston Concrete 1957-1976(Tad Stahl was the founder of Stahl Associates Architects and currently serves as Executive Architect of Burt Hill in Boston.

His career has spanned five decades, and he was the principal architect of the State Street Bank tower)At the time of my return [from London in 1957], Boston suffered from a depression-era mindset with a pervasive lack of confidence, especially in real estate. I believed strongly that great urban centers do not die, and recognized an enormous opportunity in Boston. In 1959, several colleagues and I formed a team to create the project eventually known as the State Street Bank Building at 225 Franklin Street. Working with a London property company, we acquired the site for $20 per square foot. By 1960, the team included Bill LeMessurier, my principal collaborator, and the Gilbane Building Company of Providence.

We sought to create structural efficiency and simplicity. The original design included cast-in-place frame and flat-plate floor systems with post-tensioned beams, and only twenty-eight columns. These planning efforts achieved an increase of three percent efficiency over the norm, essentially the equivalent of one additional floor at no additional cost. Despite our client's enthusiastic approval, the State Street Bank refused to become the prime tenant in a high-rise concrete building. Based on the advice of its New York real estate consultants, they demanded a steel frame building.

The new thirty-four-story scheme employed an efficient and logical steel structure. Refinements included cambered beams, elevated cantilevers, and the first comprehensive computer analysis of a high-rise steel structure conducted at MIT under Bill LeMessurier's direction. The guiding architectural concept was one of interpenetrating independent cantilevered volumes, with re-entrant corners to provide multiple exposures for offices. The exterior was developed using pre-cast concrete units to form a series of interlocking frames.

I wanted something of the substantive spirit of Boston's traditional waterfront granite warehouses in the façade detail, while expressing the reality of the cantilevered structure. The façade balances an appropriate and weighty density of concrete with geometrical precision, clarity, and a hierarchy of scale—all dramatically revealed in light and shadow.

(from http://www.overcommaunder.com/heroic/essays/tad-stahl/)

The physical facts via https://www.emporis.com/buildings/119256/225-franklin-street-boston-ma-usa :

Height: 477.00 ftFloors (above ground): 33

Construction end: 1966

Elevators: 24

Parking places: 210

An Office building with 1.082 Million square feet.