There's no exact translation, and Japanese people are likely to say that only the Japanese can understand this quintessential aspect of Japanese culture. Leonard Koren's Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers (1994, reprinted 2008) was one of the first introductions to wabi-sabi in English (there's also a sequel Wabi-Sabi: further thoughts (2015)), and he declared it to be

a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete; a beauty of things modest and humble; a beauty of things unconventional ...one of the defining aesthetic sensabilities of Japanese civilization.Originally, the Japanese words wabi and sabi had quite different meanings. Sabi originally meant 'chill', 'lean' or 'withered'. Wabi originally meant the misery of living alone in nature, away from society... Around the 14th century, the meanings of both words began to evolve in the direction of more positive aesthetic values. ... Over the intervening centuries, the meanings of wabi and sabi have crossed over so much that today the line separating them is very blurry indeed.

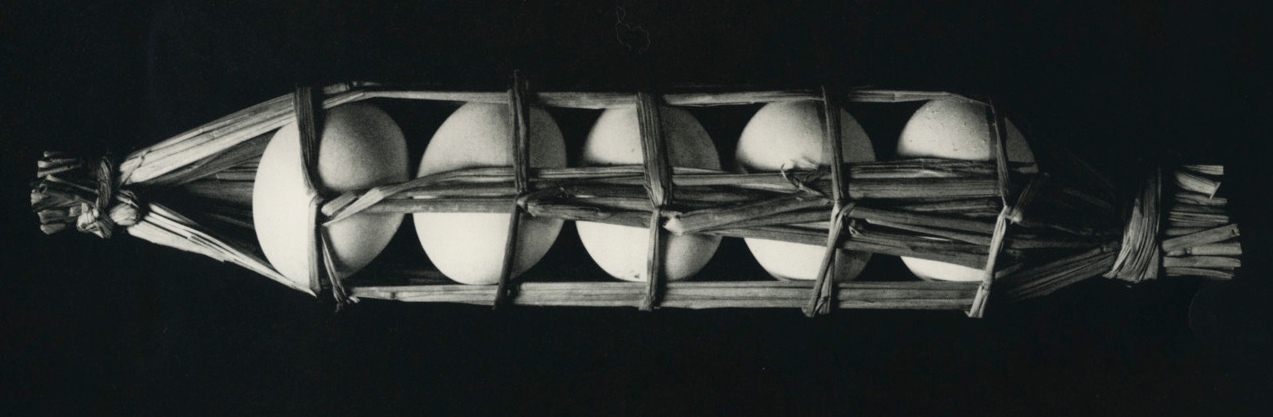

My own introduction to this complex of ideas came through How to Wrap Five Eggs: traditional Japanese packaging (1967), but there are lots of photobooks that cover the same basic ideas in other media: carpentry, textiles, ceramics, painting, garden design, flower arranging.

I recently stumbled across Andrew Juniper's Wabi Sabi: the Japanese art of impermanence (2003), which at $2.39 for the Kindle edition was just too cheap to pass up. It's an excellent English take on the subject, and discusses wabi-sabi as an aspect of Zen practice.

...an aesthetic ideal that uses the uncompromising touch of mortality to focus the mind on the exquisite transient beauty to be found in all things impermanent ... refrains from all forms of intellectual entanglement, self-regard, and affectation in order to discover the unadorned truth of nature ... (from the Introduction)And here's a passage that seems to me to speak directly to photographers, though it describes woodworkers:

A Japanese carpenter for instance will treat his tools and the materials he uses with an intense reverence. His function is to try his best to bring out the wood's inner beauty in a harmonious way. When his work is done he will not be seeking praise or gratitude for the work, for he has a personal sense of satisfaction that he has done his best and can do no more. This sense of modesty is the lifeblood of wabi sabi and saves the work of artists from being tainted by the pretensions or ambitions of an artist. Wabi sabi art must have this essential element of humility if it is to retain the purity of its spirit. (pp. 56-57)

And another:

For those inspired by the sentiments of wabi sabi and the potential it offers, there are no hard-and-fast rules on what is and what isn't wabi sabi. If something evokes feelings of an intangible yearning, then that something has wabi sabi for the person concerned. (pg. 123)

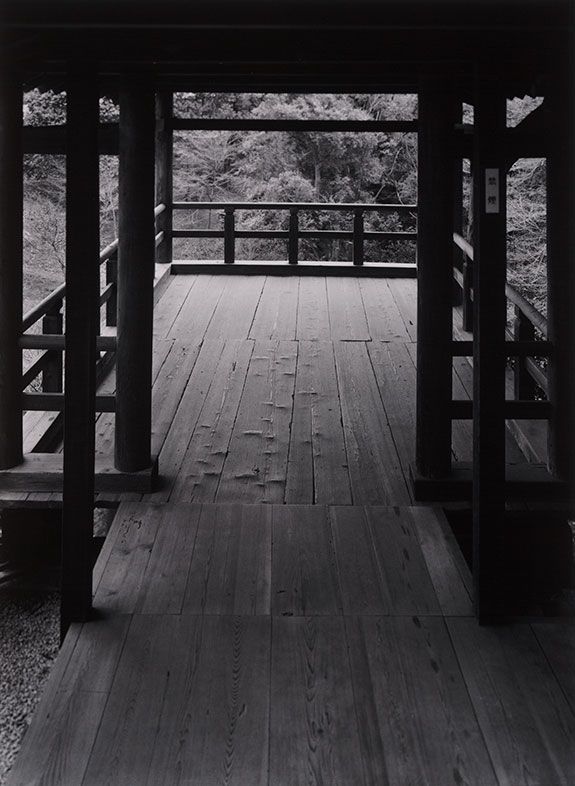

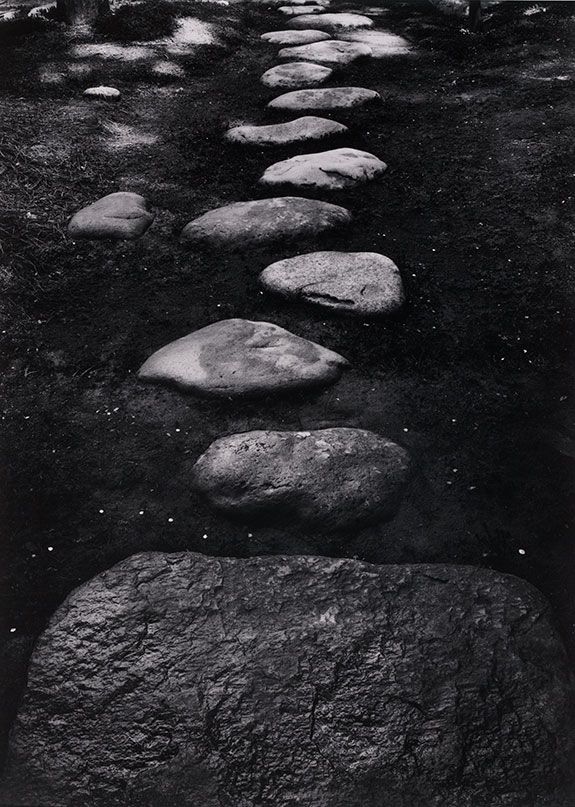

Among American photographers, the work Paul Caponigro and Michael Kenna did in Japan clearly embodies wabi sabi:

Kenna:

Literally "an intense feeling of things." An ancient term that enshrines the Buddhist idea of ephemerality. Used in art criticism to convey a sense of beautiful sadness or gentle melancholy. Its links with the beauty of impermanence make it a very close relative of the term wabi sabi. (Juniper pg. 159-160)

What is the future of wabi sabi in the modern Japan of bullet trains and digital technologies? The sad fact about wabi sabi seems a mirror image of the sad fact about black and white photography: their day is pretty much done, and they are the resort of specialists and mouldy-fig aesthetes (like some of us...) who are ageing rapidly but are still invested mightily in the mystiques of their younger days. That might be ineffably sad if one thought it important for the world to go on as we imagine it used to be.