|

|

|

Home / Authors

/ Ralph Doolin

| |

|

| Sailing through a

Waterspout |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

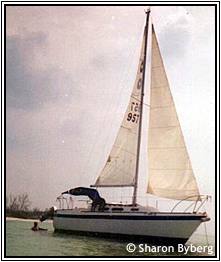

| | We were

on the Intracoastal Waterway in southwest Florida on July

15 of this year. Heading out for our normal

Saturday daysail on our 1988, 25-foot O'Day, we had a

large crew of seven on board. We had noted that it was very

stormy north of us, but the clouds seemed to be moving east

and our route was taking us to the south. We were only about

half an hour into our sail when we noticed the storm was in

fact moving toward us and was catching up to us quite quickly.

As we discussed what to do next, a waterspout touched down

about 200 yards to our north. I had never seen a tornado or a

waterspout before—it had us all mesmerized! The spout was

about 50 feet across and it came toward us very fast. Even

though there were other boats on the Waterway, we got hit. The

only thing we had time to do was let out the sails and hang

on—that was it! The jib got hung up and we couldn't free it.

When the spout hit the boat, it instantly tore our bimini top

off and with the jib still hung up, the mast went right into

the water and stayed there for what seemed like 30 seconds.

The captain, another crew person, and I were in the bow while

the remaining four crew were scattered from amidships to the

stern during the initial onslaught, and how they hung on, I

don't know—but one man didn't, and he went overboard. As the

center of the spout passed over us, the boat righted itself.

Fortunately, the man in the water was only a few yards away,

which gave him a front-row seat to watch what happened next.

| |

|

| | The

back side of the spout hit us and down we went—again! We got

turned around and headed west. The wind was so powerful this

time that it broke our standing rigging off the boat and bent

the mast. This whole episode from beginning to end lasted

about five minutes.

The waterspout was an experience I will never forget. It

was only by the grace of God that no one on the boat was

injured. We later heard reports that three waterspouts had

touched down in the vicinity of our daysail, but we only saw

the one—that was enough. I have nothing to offer to other

sailors that could help them if they are caught in this

situation except to say that if you see a spout near you, drop

your sails and pray!

Sharon's

experience seems to be a fairly typical account of

encounters between sailboats and waterspouts. In a somewhat

more famous event, John Caldwell was sailing on his

boat, The Pagan, somewhere in the mid-Pacific on a

July morning when he saw a waterspout. Having heard that

spouts have hurricane-force winds inside, whirlpools at their

bases that could suck a ship under, and a solid wall of water

that shoots up into the clouds, Caldwell did a truly

remarkable thing—he headed directly for the spout in an effort

to get under it. Most people would consider that Caldwell was

either very brave or very stupid, especially given his

location in the mid-Pacific.

Caldwell tells his tale "On Sailing through a Waterspout,"

in the Journal of Meteorology, 11:236, 1986.

"Pagan was swallowed by a cold, wet fog and

whirring wind. The decks tilted. A volley of spray swept

across the decks. The rigging howled. Suddenly it was dark as

night. My hair whipped my eyes, I breathed wet air, and the

hard, cold wind wet me through. Pagan's gunwales

were under and she pitched into the choppy seaway. There was

no solid trunk of water being sucked from the sea; no

hurricane winds to blow down sails and masts; and no whirlpool

to gulp me out of sight. Instead, I sailed into a high, dark

column from 75 to 100 feet wide, inside of which was a damp,

circular wind of 30 knots, if it was that strong. As suddenly

as I had entered the waterspout, I rode out into bright, free

air. The high, dark wall of singing wind ran away. For me,

another mystery of the sea was solved."

What is a waterspout? Obviously it is similar in nature to

a tornado over land and many sailors think of it in those

terms. But the waterspout is a unique weather phenomenon that

occurs over a body of water—no water, no spout. It is much

like a dust devil in that its formation is enhanced by

unstable weather conditions. These conditions are usually

created by warm water temperatures and high humidity in the

first few thousand feet of the air above the water's surface.

Because of these requirements, waterspouts are most likely to

occur near the coastline in the summer, though sometimes a few

form as early as mid-spring or as late as mid-autumn, and at

least according to John Caldwell, they can occur in the

mid-Pacific.

If you think that these funnel clouds are reaching down

from above, you are not alone. Many people perceive lightning

as traveling from cloud to ground, but we now know that both

waterspouts and lightning emanate upward from the ground,

rather than descending from the base of clouds, as is the case

with a tornado. There is also a difference between a true

waterspout and the case of a land-based tornado that moves

across a body of water such as a large lake. Stories of it

raining fish and frogs are not totally inaccurate with the

latter, and tornados formed in this way can be just as

devastating as their counterparts on land.

I have personally seen many true waterspouts off the coasts

of South Carolina and Georgia in the summer. One time I

actually saw three, what you might call triplets, side by side

on the leading edge of a squall line off Folly Beach—very

impressive. These true waterspouts that form over water are

defined as an intense, vertical column, or whirlpool, of low

pressure that develops on the sea surface and extends upward

to a cloud base. Waterspouts have the potential to be

extremely dangerous, with an average life cycle ranging from

two to 20 minutes. They travel at an average speed between 10

and 15 knots, with maximum wind speeds of hurricane force or

greater, however briefly realized. John Caldwell was very

lucky, if we can believe his story.

| |

|

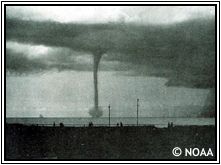

| | One of

the largest and most famous waterspouts was observed in

Massachusetts on August 19, 1896, and was witnessed by

thousands of vacationers and several scientists. It is likely

that it looked much like the spout in the old photo to the

right, which was taken of an equally famous waterspout near

Martha's Vineyard. The height of this waterspout was estimated

to be about three-quarters of a mile and its width 750 feet at

the crest, 120 feet at the center, and over 200 feet at the

base. The spray surrounding the funnel near the water's

surface was about 600 feet wide and 360 feet high. This famous

spout lasted about 35 minutes, disappearing and reappearing

three times, but most waterspouts are smaller with much

shorter life spans. This exceptional spout is an example of

those that are spawned by squall conditions associated with

thunderstorms, and in this way are similar to those same

conditions that produce tornadoes over land. The highest

waterspout ever recorded reached a height of over

one-and-a-half kilometers (about one mile)—more than four

times the height of the world's tallest building.

| |

|

| | A

recent waterspout in Tampa, FL, on June 19 made history in a

unique way. As Tiger Woods was smashing golf records,

including one that had stood since 1862, to win the US Open

Golf Tournament in Pebble Beach, CA, local Tampa TV station

WFLA-Channel 8 cut away to a weather bulletin. While Woods was

missing his birdie putt, golf fans in Tampa Bay were looking

at a picture of a waterspout over their home waters. Viewers

were so irate at missing Wood's historic finish after nearly

24 hours of network coverage that they telephoned and e-mailed

more than 3,000 complaints to the television station and local

newspapers. The waterspout did no damage, but it did put the

TV station in the Sports Broadcasting Screw-up Hall of Fame.

What should you do to avoid waterspouts? You can begin by

staying well informed about the weather. If you do not have

VHF on board, a portable weather radio designed to receive

NOAA weather broadcasts should always be aboard your boat—and

you should listen to it regularly.

Since

waterspouts tend to come from clouds with dark, flat bottoms

when there is just the first hint of rain, you should be extra

vigilant when these conditions develop. If a waterspout heads

your way, try to escape by going at right angles to its path.

The greatest danger, if you are enveloped by a waterspout, is

from personal injury caused by flying debris, just as with a

tornado. Going below, getting low in the boat, and possibly

even getting into the water might be a good practice.

Definitely put on a PFD, in the event that you do end up in

the water, and as protection against flying objects. You

probably shouldn't take your cue from John Caldwell and his

mid-Pacific exploits aboard Pagan.

|

Five Stages of Waterspout

Development

| |

|

| | Meteorologists

have been studying the formation of waterspouts for

years. NOAA Senior Scientists have distinguished five

stages of waterspout development:

- The "dark spot" phase is one in which a

prominent, circular/light-colored disk appears on the

surface and is surrounded by a larger dark area of

indeterminate shape. While not visible to the mariner

at sea level, the presence of a dark spot and an

associated funnel cloud overhead indicate that a

complete funnel is present.

- The "spiral pattern" phase represents a

pattern of light and dark-colored bands spiraling out

from the dark spot that develops on the sea surface.

- The "spray ring" phase creates a dense,

swirling ring of sea spray appearing around the dark

spot with what appears to be an "eye." When the wind

speeds reach approximately 40 miles per hour, they

begin to disperse the spray upward in a circular

pattern known as the spray vortex.

- In the "mature vortex" phase, the

waterspout, which is now visible from the sea surface

upward to the overhead cumuli-form cloud base,

achieves maximum organization and intensity.

- With the "decay" phase, the funnel and

spray vortex begin to dissipate as the inflow of warm

air into the vortex weakens. Frequently, rain showers

that develop nearby create a downdraft of cooler air

that accelerates the progression of the decay phase.

Mariners whose vessels have been hit by waterspouts

during the decay stage have reported being drenched

with a combination of salt and rainwater.

—courtesy of NOAA

|

| |

|

|

| |

|