September 26, 2010

links for 2010-09-26

-

yup. A good use of 13:45 of your time, and I TOLD you so...

September 23, 2010

September 22, 2010

links for 2010-09-22

-

a general-purpose tool, this conversion/paraphrase thing (see http://labs.slate.com/articles/plain-english/ for more, ignoring the annoying illiteracy of "it's" unless you can convince yourself that it is itself PLAIN English now grumble grumble...)

-

my dear friend Daniel Heikalo's new venture

September 19, 2010

Judt on Milosz

I don't think I had read anything of Tony Judt's writing until I revived my long-lapsed subscription to NYRB a year ago, just in time to catch his riveting last pieces. I've begun his Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, and it'll take a while to absorb its immensity. In the most recent NYRB there's a piece on Milosz's Captive Minds (fortunately not behind the paywall and well worth reading in its entirety) that reminds me of things I should have been paying attention to, or should at least have encountered. Judt unpacks the (originally Arabic) concept of 'Ketman':

The second image is that of “Ketman,” borrowed from Arthur de Gobineau’s Religions and Philosophies of Central Asia, in which the French traveler reports the Persian phenomenon of elective identities. Those who have internalized the way of being called “Ketman” can live with the contradictions of saying one thing and believing another, adapting freely to each new requirement of their rulers while believing that they have preserved somewhere within themselves the autonomy of a free thinker—or at any rate a thinker who has freely chosen to subordinate himself to the ideas and dictates of others.Ketman, in Miłosz’s words, “brings comfort, fostering dreams of what might be, and even the enclosing fence affords the solace of reverie.” Writing for the desk drawer becomes a sign of inner liberty. At least his audience would take him seriously if only they could read him...

Judt describes his own history of teaching Milosz to American students:

And indeed, when I first taught the book in the 1970s, I spent most of my time explaining to would-be radical students just why a “captive mind” was not a good thing. Thirty years on, my young audience is simply mystified: Why would someone sell his soul to any idea, much less a repressive one? By the turn of the twenty-first century, few of my North American students had ever met a Marxist. A self-abnegating commitment to a secular faith was beyond their imaginative reach. When I started out, my challenge was to explain why people became disillusioned with Marxism; today, the insuperable hurdle one faces is explaining the illusion itself.

At this point I started to anticipate his argument, thinking "but isn't this just what they've done themselves?", but I was unprepared for the clarity with which Judt sums it up:

Today, we can still hear sputtering echoes of the attempt to reignite the cold war around a crusade against “Islamo-fascism.” But the true mental captivity of our time lies elsewhere. Our contemporary faith in “the market” rigorously tracks its radical nineteenth-century doppelgänger—the unquestioning belief in necessity, progress, and History. Just as the hapless British Labour chancellor in 1929–1931, Philip Snowden, threw up his hands in the face of the Depression and declared that there was no point opposing the ineluctable laws of capitalism, so Europe’s leaders today scuttle into budgetary austerity to appease “the markets.”But “the market”—like “dialectical materialism”—is just an abstraction: at once ultra-rational (its argument trumps all) and the acme of unreason (it is not open to question). It has its true believers—mediocre thinkers by contrast with the founding fathers, but influential withal; its fellow travelers—who may privately doubt the claims of the dogma but see no alternative to preaching it; and its victims, many of whom in the US especially have dutifully swallowed their pill and proudly proclaim the virtues of a doctrine whose benefits they will never see.

Above all, the thrall in which an ideology holds a people is best measured by their collective inability to imagine alternatives. We know perfectly well that untrammeled faith in unregulated markets kills: the rigid application of what was until recently the “Washington consensus” in vulnerable developing countries—with its emphasis on tight fiscal policy, privatization, low tariffs, and deregulation—has destroyed millions of livelihoods. Meanwhile, the stringent “commercial terms” on which vital pharmaceuticals are made available has drastically reduced life expectancy in many places. But in Margaret Thatcher’s deathless phrase, “there is no alternative.”

September 18, 2010

Two eloquent passages from the day's reading

I've had Dwight Macdonald's Parodies: An Anthology from Chaucer to Beerbohm --and After (1960) for years, and nibbled at it betimes. The September 20th issue of The New Yorker has a Louis Menand review of The Oxford Book of Parodies (2010) which has this beautifully clear --indeed, all but anthropological-- summary of what HAPPENED in the 50 intervening years:

In 1960, though, Macdonald was pushing on a door where there was still some resistance. Since then, literature has ceased to be the dominant middle-class cultural preference, and the barrier between the authentic and the parodic has collapsed. A "diffused parodic sense" is everywhere. The culture is flooded with ironic self-reflexivity and imitations of imitations: travesties, spoofs, skits, lampoons, pastiches, quotations, samplings, appropriations, repurposings. This has happened at the low end (television commercials that are parodies of television commercials) and the high (postmodern fiction). And since 1960 a giant continent of mainstream entertainment has emerged of which parody is the foundation, from National Lampoon, Monty Python, and "Saturday Night Live" to Spy, Weird Al Yankovic, "The Simpsons," and The Onion....even the members of reading clubs could use some guidance making sense of a culture in which almost nothing is taken seriously unless it first makes fun of what it is. This practice may be partly self-protective: it is harder for someone to subvert you if you are already subverting yourself. But self-parody can also convey authority. The "Daily Show" is a parody of a news program, and a lot of people rely on it for news.

Still, anthologically speaking, where to start? When everything is quasi-parodic, when everything presents itself with a wink of self-conscious exaggeration, then it may be that parody is finished as the kind of genre you can represent within the confines of an Oxford Book... (pg 80)

And an hour or so later I found myself immersed in Joshua Clover's "Busted: Stories of the Financial Crisis" from September 20 issue of The Nation, staring at another brilliant bit of analytical abstraction:

...When one converts, say, collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps into a folksy story about the neighbors and their home insurance, the crisis appears more legible than its components, those acronymic phantasms of fictitious capital traded by the blind protocols of shell companies hoping to arbitrage a few billion pennies from minuscule imbalances in a great global system.

What those two passages share is an exemplary clarity of analysis and expression, to which I wish I could rise myself. Still, I know it when I see it.

September 14, 2010

links for 2010-09-14

-

various bits of Latin revealed, a fascinating puzzle

September 13, 2010

links for 2010-09-13

-

"Besser kein rohes Fleisch essen!" indeed

-

Bruce Sterling is nothing if not prescient

September 12, 2010

September 10, 2010

September 09, 2010

links for 2010-09-09

-

(just when I was getting a bit jaded with podcasting)

September 06, 2010

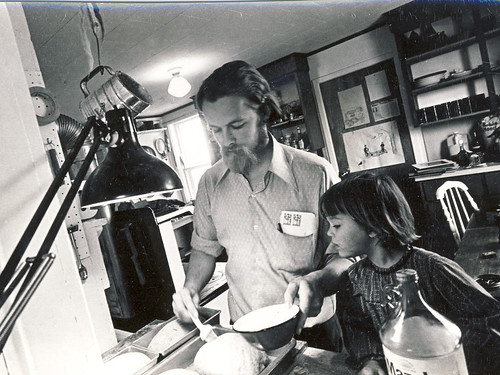

Photographic ruminations

What part does equipment play in what a photographer is able to do? Clearly, in the last 6 months Betsy's 60mm macro lens has taken her into almost magical realms of vision and transformed her capability to capture what she could see. My own fascination lies with ultra wide angle perspective, ever since the adventures in the 1970s with the 21mm Zeiss lens on the now-defunct Nikon rangefinder camera.

While there are ultrawides for digital cameras (I'm actively considering the Tokina 11-16mm), they're pretty large and not so very portable, but tempting nonetheless.

At the moment I find myself lusting after a smaller and less obtrusive solution, Voigtländer's Color-Skopar 21mm on a Bessa R4A body, a 35mm film camera. I happened upon a FlickRiver pool for that lens, and I continue to slaver. My birthday is approaching...

September 05, 2010

Sandburg vs. Frost

Harper's put this up today:

The policeman buys shoes slow and careful; the teamster buys gloves slow and careful; they take care of their feet and hands; they live on their feet and hands.…and I was reminded of Robert Frost's sentiments re: Carl Sandburg, as disclosed in a letter to Lincoln MacVeagh (quoted in Paul Muldoon's essay on The American Songbag, in the Marcus and Sollors New Literary History of America, pp 609-610):The milkman never argues; he works alone and no one speaks to him; the city is asleep when he is on the job; he puts a bottle on six hundred porches and calls it a day’s work; he climbs two hundred wooden stairways; two horses are company for him; he never argues.

The rolling-mill men and the sheet-steel men are brothers of cinders; they empty cinders out of their shoes after the day’s work; they ask their wives to fix burnt holes in the knees of their trousers; their necks and ears are covered with a smut; they scour their necks and ears; they are brothers of cinders.

–Carl Sandburg, Psalm of Those Who Go Forth Before Daylight, first published in Cornhuskers (1918)

We've been having a dose of Carl Sandburg. He's another person I find it difficult to do justice to. He was possibly hours in town and he spent one of those washing his white hair and toughening his expression for his public performance. His mandolin pleased some people, his poetry a very few and his infantile talk none… I heard someone say he was the kind of writer who had everything to gain and nothing to lose by being translated into another language.

Some balance is restored, perhaps, by this from Christian Wiman in his essay on Frost in the same New Literary History of America (p 540):

Of course, there are more shoals than poems, more confusion than the songs that seem, briefly, to contain and control it. This is particularly true for modern poets and their inheritors. With this in mind, the buffoonery and bluster of Frost's public persona become, perhaps a bit more explicable, as do all the cutesy, folksy poems that seem to have been written solely in the service of this persona.Honors about even, don't you think?