wabi-sabi and Japanese aesthetics

from Donald Keene "Japanese Aesthetics" in Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: a reader (BH221 .J3 J37 1995):

Some years ago, while writing an essay on Japanese tastes, I chose four characteristics that seemed to me of special importance: suggestion, irregularity, simplicity, and perishability. These still seem to me a valid way to approach the Japanese sense of beauty, though I am fully aware that they do not cover everything. Generalizations are always risky. If, for example, one says of the No drama that it is a crystallization of Japanese preferences for understatement, muted expression, and symbolic gesture, how is one to explain why the Japanese have also loved Kabuki, which is characterized by larger-than-life poses, fierce declamation, brilliant stage effects, and so on? (pg. 29)The Japanese have been partial not only to incompleteness but to another variety of irregularity, asymmetry. This is one respect in which they differ conspicuously from the Chinese and other peoples of Asia... Japanese writing that is not specifically under Chinese influence avoids parallelism, and the standard verse forms are irregular numbers of lines --five for the tanka, three for the haiku. This is in marked contrast to the quatrains that are typical poetic forms not only in China but throughout most of the world... (pg. 32)

Japanese children are taught in calligraphy lessons never to bisect a horizontal stroke with a vertical one: the vertical stroke should always cross the horizontal one at some point not equidistant from both ends. A symmetrical character is considered to be 'dead'. The writing most admired by the Japanese tends to be lopsided or at any rate highly individual, and copybook perfection is admired only with condescension... (pg. 33)

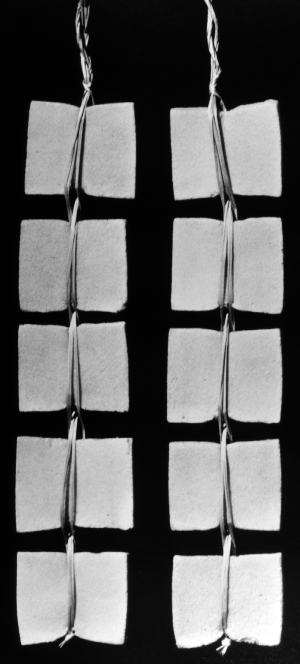

Irregularity is also a feature of Japanese ceramics, especially those varieties that are most admired by the Japanese themselves... The Japanese have produced flawless examples of porcelain, and these too are admired, but are not much loved. Their perfection, especially their regularity, seems to repel the hands of the person who drinks tea from them, and flowers arranged in porcelain vases seem to be challenged rather than enhanced... (pg. 33)

(quoting Kenko [1282-1350])

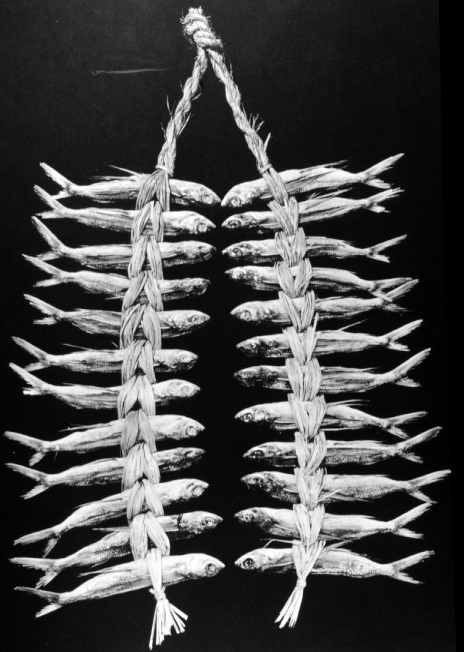

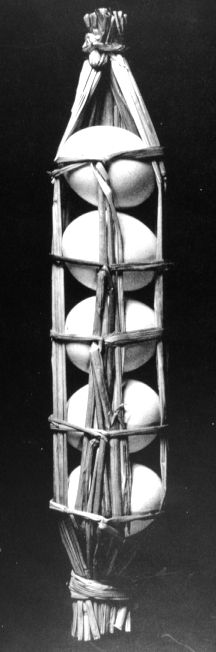

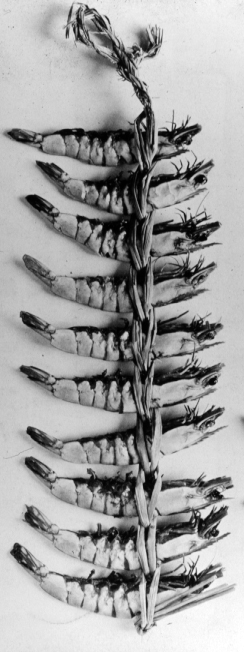

The intelligent man, when he dies, leaves no possessions. If he has collected worthless objects, it is embarrassing to have them discovered. If the objects are of good quality, they will depress his heirs at the thought of how attached he must have been to them. It is all the more deplorable if the possessions are ornate and numerous. If a man leaves possessions, there are sure to be people who will quarrel disgracefully over them, crying, "I'm getting that one!" If you wish something to go to someone after you are dead, you should give it to him while you are still alive. Some things are probably indispensable to daily life, but as for the rest, it is best not to own anything at all. (pg. 35)Japanese food lacks the intensity of flavor found in the cuisines of other countries of Asia. Spices are seldom used, garlic almost never... the barely perceptible differences in flavor between different varieties of raw fish are prized and paid for extravagantly. The taste of natural ingredients, not tampered with by sauces, is the ideal of Japanese cuisine; and the fineness of a man's palate is often tested by his ability to distinguish between virtually tasteless dishes of the same species... (pg. 37)

(quoting the novelist Natsume Soseki [1867-1916]):

When I was in England, I was once laughed at because I invited someone for snow-viewing. At another time I described how deeply the feelings of Japanese are affected by the moon, and my listeners were only puzzled... I was invited to Scotland to stay at a palatial house. One day, when the master and I took a walk in the garden, I noted that the paths between the rows of trees were all thickly covered with moss. I offered a compliment, saying that these paths had magnificently acquired a look of age. Whereupon my host replied that he soon intended to get a gardener to scrape all this moss away. (pg. 40)