“Hm.” I remember thinking. “Need to provide entrée to the collectors who found, preserved, annotated, packaged, released, and loved this music. And to the venues and mass media outlets that brought it to broader publics…” and the more I look into the background, the more stuff I find to explore and include, so more searches get done, more stuff gets ordered and read and heard. Case in point:

Just flew in through the transom: The Harry Smith B-Sides (“the flip side of 78-rpm records that Harry Smith included on the Anthology of American Folk Music”).

Who needs this? Certainly the music-obsessed, those who have grown up with the Anthology (1952, reissued on CDs 2007… and download !!liner notes!!) and its sequelæ Anthology Of American Folk Music Volume 4 (Revenant Records 2000) and The Harry Smith Project: The Anthology Of American Folk Music Revisited (2006), and the lucky few who followed gadaya’s labor of love MY OLD WEIRD AMERICA An exploration of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music blog when it was alive for downloads of the Variations.

The B-Sides are fully as revelatory as the 84 cuts on the original Anthology:

a mirror image of the Anthology… a way to hear the complete statement of each 78RPM disc… as they were originally released in the 1920s and 1930s…

Most people interested by the Smith Anthology will agree that it stands as an esoteric beacon outside the whole dysfunctional culture system. Just like when it was first issued in 1952, you still won’t hear the music of the Smith Anthology on the radio, on TV or on the front pages of the internet…

By releasing his Anthology to the audience of Folkways Records, Harry Smith dropped an extraordinary rural working class culture bomb on a New York City world of artists, bohemians, radicals, and city musicians… (Eli Smith, B-Sides liner notes)

A New York Times story on the B-Sides: How to Handle the Hate in America’s Musical Heritage

The 1927 Bristol recording sessions (the Big Bang of country music) captured 76 songs, recorded by 19 performers or performing groups, including the Carter Family.

The saga of recording Black musicians in the 1920s was somewhat more haphazard. There was a booking agency for the Black vaudeville circuit, the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA, referred to by Ma Rainey as ‘Tough On Black Asses’) that dealt with jazz, comedians, dancers and (mostly female) blues acts (Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith). Country blues artists were mostly too small-time and local for TOBA, and were recorded in studios outside the South (e.g., “Paramount Records, based in Port Washington, Wisconsin. The company was a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company, who also made phonographs…”) but the musicians were recruited by

“field scouts” [used] to seek out new talent, though this is a somewhat grand name for men the likes of HC Speir, who ran stores in the South and simply kept an eye out for local musicians. Through Speir they recorded Tommy Johnson and, most importantly, Charley Patton. It was Patton that took Son House, Willie Brown and Louise Johnson to Paramount’s new studios in Grafton WI in 1930.

Several record companies had catalogs of “Race Records” made for a specifically Black rural public, and it is these disks that were rescued by record collectors in the 1960s.

Thinking about mass media and Nacirema musics, one of the constants for most of the last century has been Grand Ole Opry, which was first broadcast from Nashville in 1925 and came to blanket the rural South with versions of aural and, eventually with TV, visual imagery of regional culture. Separating the authentic and vital from the stereotyped and bogus is challenging, and just how accurate and inclusive the picture was/is/can be argued endlessly. The intrusions of commercial elements are everywhere, and might as well be acknowledged while we hunt for whatever purity they blanket. Resort complexes like Opryland USA and Dollywood and Branson MO and Graceland have drawn crowds seeking ‘authentic’ experiences, and have provided income for entertainers.

The cultural complexity of the Showcase experience is exemplified by Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973), who was a lawyer, performer, researcher, field collector, impresario, and tyrant for the cause of what he spoke of as “mountain music.” His Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville NC (first in 1928) was the paradigm for many other folk festivals.

Lunsford himself despised the commercialism and cultural nonsense he saw in Asheville’s Rhododendron Festival, and opposed the stereotyping of mountain folk as backward and ignorant. Still, as a performer he could produce material as bogus as Good Old Mountain Dew

A documentary on Lunsford, This Appalachian Music Man Lived A Beautiful Life, in which Alan Lomax shows up:

and David Hoffman’s Bluegrass Roots 1965 was filmed in a mountain tour conducted by Lunsford:

John (1867-1948) and Alan (1915-2002) Lomax are giants in the history of discovering and recording Nacirema music in the field. A site from the Musical Geography Project offers maps of Lomax travels. John Szwed’s biography of Alan Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World is excellent, and Duchazeau’s Lomax: Collectors of Folk Songs is a charming graphic-novel portrayal of a 1933 Lomax collecting foray into the South. Among the interesting videos on Alan Lomax:

Cultural Equity has a vast collection of Alan Lomax field materials

Wikipedia lists more than 50 American folk song collectors, and American Folklife Center has a page of women collectors, including Frances Densmore (1867-1957), Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle (1891-1978).

Mike Seeger’s fieldwork in Appalachia brought Dock Boggs (1898-1971) to modern audiences and covered a wide range of southern styles of music and dance. Just Around The Bend: Survival & Revival in Southern Banjo Sounds was his last documentary film, and there are several documentary CDs and DVDs: Close to Home: Old Time Music from Mike Seeger’s Collection, 1952-1967, Mike Seeger Early Southern Guitar Styles, Early Southern Guitar Sounds, Southern Banjo Styles #1 Clawhammer Varieties & more, Southern Banjo Styles #2-Early 2- and 3-Finger Picking, Southern Banjo Sounds, besides his work with the New Lost City Ramblers, his sister Peggy, and various other musicians.

Art Rosenbaum’s Art of Field Recording (1 and 2) (available via Dust to Digital) offers a wealth of field recordings made 1959-2010.

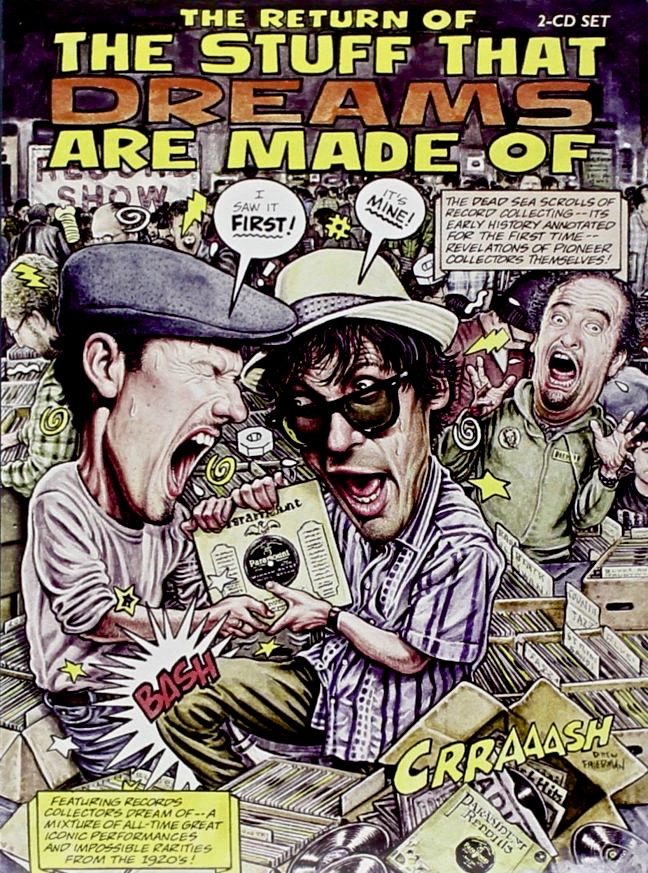

Record collectors inhabit a separate documentary world, well described in Amanda Petrusich’s Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records.

…an intense, competitive, and insular subculture with its own rules and economics—an oddball fraternity of men (and they are almost always men) obsessed with an outmoded technology and the aural rewards it could offer them. Because 78s are remarkably fragile and were sometimes produced in very limited quantities, they’re a finite resource, and the amount of time and effort required to find the coveted ones is astonishing. The maniacal pursuit of rare shellac seemed like an epic treasure hunt, a quest story—an elaburate, multipronged search for a prize that may or may not even exist. (pg. 4)

Among collectors of 78s, Joe Bussard stands out as a National Treasure. A Fretboard Journal profile introduces his rather unique personality:

Joe Bussard has an interesting theory: Musical forms seem to lose their value when the electric bass is introduced. “That goddamn electric bass ruined everything!” he shouts. “I went to Trashville—I mean Nashville—in ’57 to see the Opry, and I asked for my money back, I’ll tell you that right now. They didn’t have shit I wanted to hear. Garbage! When rock come in, I didn’t have any interest in anything that damn dumb! Elvis and all that bullshit! I already knew better than to fall for that, buncha goddam shit for retarded 4-year-old kids!”

but its essence is best appreciated in videos:

Joe has been very open-handed with his collection, making tapes for people and contributing to a vast array of compilations. There’s a video Desperate Man Blues: Discovering the Roots of American Music that I’d love to get my hands on. Looks like I had it in 2007 from Netflix, and I’ve requested it again.

Besides his Fonotone Records recording business which ran for a decade or so and lately produced a remarkable compilation

Massive 5CD set of American Primitive music unearthed for the first time (in various styles: Jug Band, Country, Old Time, Blues and Bluegrass), recorded and documented by Joe Bussard’s 78-RPM Fonotone label, 1956-1969 — not one track previously on CD before. Incredible package featuring 131 tracks over 5 discs, 160-page perfect-bound book, 17 full-color postcards, 3 record label reproductions in souvenir folder and a nickel-plated Fonotone Records bottle opener(!) — all packaged in a deluxe cigar box.

Joe Bussard recorded the young John Fahey in 1959-1960.

John Fahey deserves mention under Collectors for his part in the rediscovery of Bukka White and Skip James (both of whom had made mighty 78s in the 1920s), described in detail in Dance of Death: The Life of John Fahey, American Guitarist, and for the research he did on Charley Patton, and other Revenant Records collections American Primitive, Vol. 1: Raw Pre-War Gospel (1926-36) and American Primitive Vol . 2 – Pre-War Revenants (1897 – 1939).

Fahey’s life was a trainwreck, with occasional bright interludes, and is perhaps best discussed under Guitar Heroes.

The fraternity of collectors is nicely documented via Mainspring Press (“Information and Resources for Historic-Sound Enthusiasts”, including Discographies). Their blogroll provides links to Excavated Shellac (mostly concerned with non-US sources) and Sound of the Hound (“dedicated to the story of how recording came into being and how it conquered the world”). See also Amanda Petrusich on John Heneghan and The Great 78 Project at the Internet Archive.

Some collectors have specialized in “ethnic” 78s (a whole other subset of my musical world), including Dick Spottswood (who grew up near John Fahey) and Ian Nagoski (of Canary Records and Fonotopia) and Karl Signell. See also 78rpm Collector’s Community (“a social network for collectors of 78rpms recordings, phonographs, memorabilia, recording machines and the history of the 78 rpm recording era”)

Experiments with recording at 78 RPM include American Epic (and accompanying CD and book).