n.b. that this posting owes a lot to my reading of Juan Cole’s 31 July “What is Hizbullah?”, and particularly to this paragraph:

Thus, a very large number of the Pushtuns in Afghanistan are sub-nationalists with a commitment to Pushtun dominance. They deeply resent the victory of the Northern Alliance (i.e. Tajiks, Hazara Shiites, and Uzbeks) in 2001-2002. A lot of what our press calls resurgent “Taliban” activity is just Pushtun irredentism. There are approximately 14 million Pushtuns in Afghanistan and another 14 million or so in Pakistan.

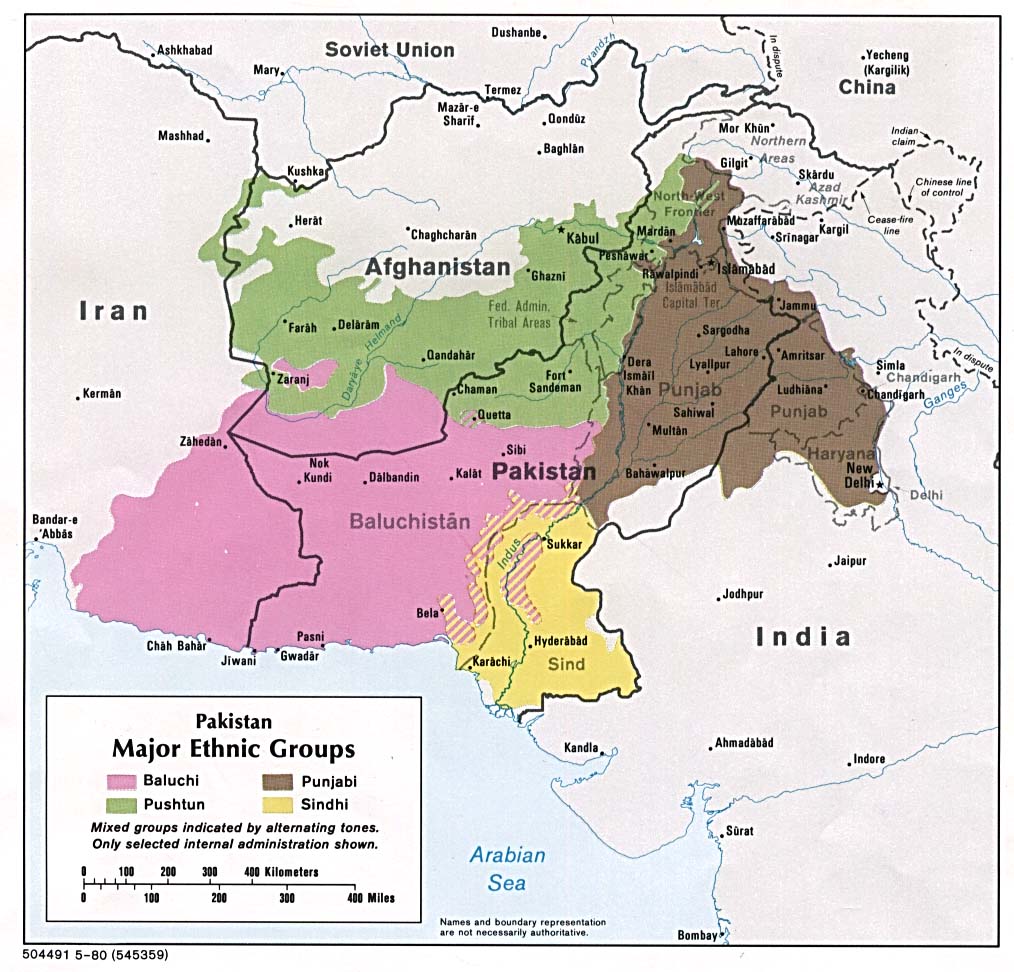

Consider this approximation to territory of ethnic groups in and around Afghanistan, and focus on the green ‘Pushtun’ territory:

(from Wikipedia, and the Perry-Castañeda Library)

Now reflect on the struggles of the British Raj (and its successors) on the North West Frontier Province, mostly with Pathans/Pakhtuns (and sub’tribes’ like the Afridis of the Khyber Pass area). I think back to my own fascination of 35 or so years ago with Frederik Barth’s work on the Swat Pathan (Political leadership among Swat Pathans, 1965 or is it 1959?), from whence a bit of googling took me to David B. Edwards’ “Learning from the Swat Pathans: Political Leadership in Afghanistan, 1978-97” (American Ethnologist, Vol. 25, No. 4. [Nov., 1998], pp. 712-728), which includes this interesting springboard into rethinking yet again my own trajectory as an anthropologist (some emphasis added):

The 20 years of civil war in Afghanistan–20 years that have also seen an Islamic revolution in Iran, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and myriad tribal and ethnic conflicts– have been a time in which cultural anthropology has immersed itself in a series of insular debates over the nature and validity of the anthropological enterprise. And while the discipline as a whole has gained by being more self-conscious about modes of representation and how it ascribes authority, the debates about how anthropologists create texts have had pernicious effects, first, of isolating anthropology from other disciplines and larger international concerns and, second, of constricting research within anthropology by making some researchers leery of declaring anything in too authoritative a manner for fear of representing those among whom they have lived and about whom they write in a way that others might deem culturally insensitive, politically suspect, or simply naive.

The debates I have been discussing in this article predate the postmodern turn in anthropology, and I must admit that I have found it bracing to reread these works that I last read in graduate school in the early 1980s. There is a seriousness about anthropology’s ability to analyze events in the world, as well as a quality of nonironic engagement –with the people being studied and the potential larger significance of the debate itself– that I find missing in much anthropology today. (pp 726-727)

This excursion resulted from thoughts about the depths (or is it shallownesses) of misunderstanding of complexities and historical background that are endemic to the US government’s every move in the current unpleasantnesses. Daniel Levy (in a piece in Haaretz, “Ending the neoconservative nightmare”, 4 August) summarizes clearly: “An America that seeks to reshape the region through an unsophisticated mixture of bombs and ballots, devoid of local contextual understanding, alliance-building or redressing of grievances, ultimately undermines both itself and Israel…”

Our mass media and political creatures talk of “the Taliban” as if they were simply freedom-hating medieval fundamentalist fanatics, and tar them with the “terrorist” brush and the label of “bad guys” –no effort is made to understand from whence the movement springs, or to examine its historical precedents.

There are some useful correctives: Wikipedia on Taliban is a pretty good summary, especially taken (as Wikipedia articles generally should be) with the Discussion and History. The link to Wikipedia’s Pashtun article notes that “The Pashtuns are the world’s largest segmentary lineage (patriarchal) tribal group in existence…”, a fact not unrelated to the resilience of Pashtun/Pathan/Pushtun/etc in the face of what they see as outside interference in their affairs.

I have no interest in being an apologist for Taliban or Pathan or whatever, but “policy” based on ignorant labels and wilful neglect of historical context isn’t likely to produce constructive results. I found another article by David B. Edwards (“Mad Mullahs and Englishmen: Discourse in the Colonial Encounter”, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 31, No. 4 [Oct., 1989] , pp. 649-670) which provides the historical background for the recently-resurrected image of the “Mad Mullah” that infests the mass media version of current events (whether in Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon…), and relates the tale of Winston Churchill’s North West Frontier journalism. The article, centered in events in 1897, has many points of contact with the present. Just a few quotations:

Establishing the enemy as fanatical denies him moral status and affords those whose moral superiority is thus affirmed a free hand in defending their interests. (pg. 655)

Like miracles, metaphors mediate between discontinuous domains of experience, make the inchoate subject to the determination of the familiar, and generally provide a moral ground to the experience of events. (pg. 656)

The effectiveness of metaphor stems less from the similarity between two objects than in the mutability of perception itself. Metaphors have the power to transform the real and make it seem to be something other than what it had always seemed before. They achieve their effect by violating the separation of objects and physical processes. They disrupt the categories by which we organize the world and, in doing so, fuel the suspicion that the world may not be as it appears and that our knowledge of it is less than what it should be. Thus, the potency of metaphor derives from the possibility that a resemblance recognized on the surface of language will cause a fundamental transformation in the way we perceive, organize, and express our experience of the world. (pp. 656-657)

In the search for up to date information on the Wily Pathan, I’m not sure how to evaluate The Talibanization of the North-West Frontier by Sohail Abdul Nasir (in the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor), which seems thoughtful and well-informed (noting, for example, that local Taliban are a nativist movement, “concerned with not only the enforcement of Sharia law, but also the waging of jihad against intruders [i.e., U.S.-led coalition forces] in Afghanistan”). The identity and connections of the Jamestown Foundation are somewhat suspect, but perhaps I should relax my discomfort level in the face of what seems to be clear reporting by Sohail Abdul Nasir, and simply hope that his perspective will inform those in Washington of whom I am generally critical. See voltairenet.org analysis of Jamestown Foundation, with this conclusion in the final paragraph:

…the Jamestown Foundation is only an element in a huge machine, which is controlled by Freedom House and linked to the CIA. In practice, it has become a specialized news agency in subjects such as the communist and post-communist states and terrorism. Although it publishes high quality information on issues that can be checked up, it does not hesitate to launch the most blatant imputations on the rest, thus providing neo-conservative think tanks with a world image that matches their ghosts and justifies their policy.